When Zeyan Liew joined a Danish team that was studying a large, national database of mothers and their children in 2011, he was interested in understanding brain development in children. “ADHD [attention deficit hyperactivity disorder] and autism were the two fastest-growing neurological and behavioural disorders at that time,” he recalls. “We and other scientists were not sure what was driving these increasing trends.”

It was difficult to tease out, Liew says, because greater parental awareness and better diagnosis had a role in the rise in ADHD cases. “The question was, are there real increases?” says Liew, now an epidemiologist at the Yale School of Public Health in New Haven, Connecticut.

Genetic heritability underlies many cases of ADHD, but genetics cannot explain why the number is increasing — more than 20-fold in recent decades, according to some estimates1.

Nature Outlook: ADHD

The team’s data showed that more than half of mothers had taken a particular drug during pregnancy, often at high doses and for long durations, making it a suspect.

That drug was N-acetyl-para-aminophenol, known as paracetamol in Europe, and as acetaminophen in the United States, Japan and many other countries. It is marketed under various brand names, including Panadol and Tylenol, and it is a component of more than 600 products for pain and fever relief2. It has long been considered one of the safest drugs to take during pregnancy, avoiding the serious risks to the fetus posed by the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as aspirin and ibuprofen, and opioids. Worldwide, more than half of women take it during pregnancy.

But a growing body of evidence now shows increased rates of ADHD and other neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism spectrum disorder, in children whose mothers took the drug during pregnancy. The potential link had a moment in the public spotlight in September 2025, when US health secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr and President Donald Trump pointed to paracetamol as a cause of autism and urged pregnant women to avoid the drug altogether.

The evidence is inconsistent, however. Some studies show a stronger association than others, and some have found no increased risk at all. “The science between prenatal acetaminophen exposure and specifically autism is not settled, and it is premature to declare this is a proven cause,” says Liew. “We certainly should not make people fear using a treatment when it is needed and when there is no alternative.”

Many women do not even think of paracetamol as a drug, says David M. Kristensen, a molecular physiologist at Roskilde University and Copenhagen University Hospital in Denmark. Kristensen is one of the authors of a consensus statement calling for better awareness of links between paracetamol and various neurodevelopmental, reproductive and urogenital disorders2. “What was fuelling our concern,” says Kristensen, “was a lot of women not realizing that this is a real medication with real side effects.”

Cause for concern

Paracetamol is hardly a new drug. It was first developed in 1878 and has been available without a prescription since the 1950s. Over the years, it has become an increasingly popular choice because it had few immediate side effects. By 1980, sales of paracetamol exceeded those of aspirin in most countries.

The fact that two trends increased over the same period — the number of diagnosed cases of ADHD and other neurodevelopmental disorders, and the use of paracetamol — “doesn’t prove anything”, says Liew. “Lots of things change over time.”

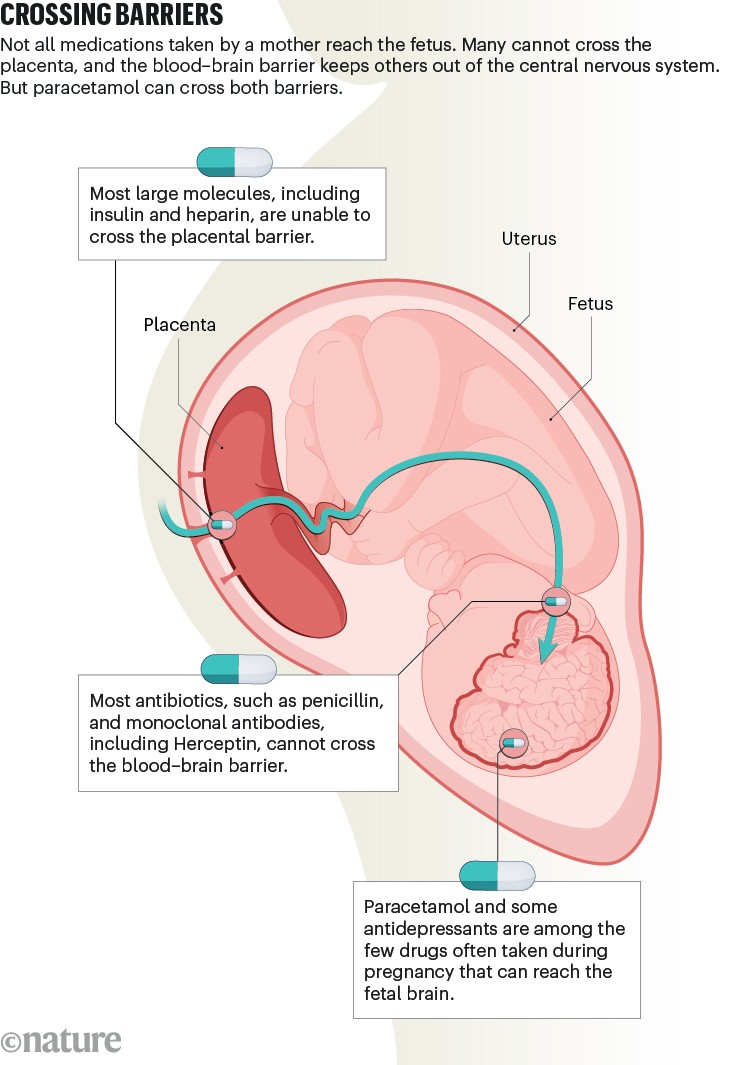

What did raise concern, however, was research showing the drug’s effect on the fetus. Studies in animals and humans showed that paracetamol affected reproduction in those exposed to it in the womb, leading to undescended testes3 and problems with ovary development4, Kristensen says. Paracetamol is an endocrine disruptor — a class of chemical that can affect hormones essential to healthy neurological and reproductive development2. In pregnancy, it crosses the placenta, which often shields the fetus from infections and toxic compounds, and it can reach the fetal brain by crossing the blood–brain barrier (see ‘Crossing barriers’).

Infographic: Alisdair Macdonald

A 2013 study in Norway of almost 50,000 three-year-olds found that those whose mothers had taken paracetamol during pregnancy were more likely to have a range of neurological problems, affecting communication, motor development, behaviour and temperament, than were siblings who were not exposed to the drug5.

At the same time, Liew and his colleagues were conducting the first study to find out whether there was a link with ADHD6. The study included more than 64,000 children drawn from the Danish database, followed up until the age of about 11. It linked paracetamol use during pregnancy to increased risk of ADHD and hyperkinetic disorder, a severe form of ADHD. And the longer the woman took the drug during her pregnancy, the higher the risk.

Liew’s team was cautious about reaching conclusions when the study was published in 2014. The paper “was really just trying to say we discovered this association after we controlled for a long list of maternal factors. There’s something to be further investigated,” said Liew.

The study kicked off a decade of research. So far, 47 studies, including the original Danish one, have examined paracetamol’s relationship with neurodevelopmental disorders in children, including 20 studies of ADHD, eight of autism spectrum disorder and 18 of other neurodevelopmental disorders. The studies were conducted in the United States, Taiwan, Canada and Europe.

Most studies have found some association. But some found no link, making it difficult to reach conclusions. Even the studies that found an association showed varying levels of risk, says Brennan Baker, who studies public health at the University of Washington and Seattle Children’s Hospital. Pooled together, the studies show that self-reported use of paracetamol is linked to 30% increases in odds for ADHD7.

Three studies that actually measured paracetamol in pregnant women or newborns, however, found a much higher risk, Baker says. One of his studies found that the risk of ADHD increased by 143% when paracetamol was detected in the meconium (first faeces)of newborns, and higher levels of paracetamol were associated with higher risk8. Another study of paracetamol in plasma from umbilical cords found that infants in the top third of paracetamol levels had a 186% higher risk9. In Baker’s latest study10, if paracetamol was found in the mother’s plasma during the second trimester, the risk of ADHD increased by 215%.

Debating the evidence

Based on the growing evidence, in 2021, a group of European and US researchers, including Liew and Kristensen, published a consensus statement reviewing the studies to that point2. They recommended that pregnant women avoid paracetamol, taking it only if there is a medical reason, in consultation with their physician or pharmacist, and at the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible time.

The publication met with “some pushback”, says Kristensen. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists said the evidence was not strong enough. Some of Kristensen’s scientific colleagues said the statement was “alarmist”. “They said we were making women unnecessarily nervous,” he says.

Another group of researchers in maternal and child health, led by Sura Alwan, an epidemiologist who studies birth defects at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, published a counter-statement, arguing that there was inadequate evidence to reach conclusions about cause and effect11.

Alwan and her colleagues found several problems with the research. “Many studies were not designed to test for causality,” she says. “Exposure most of the time was self-reported. The timing and dose issues were not reported or coarse. There were concomitant illnesses and medications that were unevenly measured.”

Other studies have found no effect of paracetamol on the risk of ADHD, autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders. One 2024 study12, for example, looked at more than 1 million mothers and almost 2.5 million children whose data were in a national registry in Sweden. As with other studies, this one found associations, albeit small ones, between paracetamol use and subsequent ADHD and autism. But the associations vanished when the children’s risk was compared with that of their siblings.

Brian Lee, an epidemiologist at Drexel University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, who co-authored the study, thinks that the association could reflect underlying health conditions and genetic factors in the mothers who took paracetamol. “People who take acetaminophen during pregnancy are inherently different from those who don’t. People who use the medication are going to be sicker in some way than people who don’t use the medication,” he says. “There are studies showing that the maternal predisposition for ADHD and autism is associated with more headaches, more migraines and more pain during pregnancy, just overall.”

To shed light on the conflicting findings, in 2025, a group of researchers published an evaluation of all the published studies1. “We needed a 10,000-foot overview of the evidence,” says Diddier Prada, a physician and environmental epidemiologist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. “We cannot take a decision based on just one study.”

They used an established, objective method, and found that the studies showing an association between paracetamol use in pregnancy and neurodevelopmental outcomes had good study designs. The review concluded that there was strong evidence of a relationship with ADHD, and some high-quality studies provided very strong evidence, such as a dose–response effect, “suggesting that increasing exposure is associated with increasing risk”, Prada says. Furthermore, the studies that did not show an association had methodological problems, he adds, such as a small sample size, a lack of dose information or a lack of biological testing.

The analysis criticized the Swedish study because it showed that only 7.5% of pregnant women took paracetamol, based on midwife interviews with the women, a figure much lower than other published rates. This could indicate that most of the women who used the drug were missed.

Lee disagrees with that conclusion, pointing out that use estimates vary between studies and countries. Obstetricians on the study’s team found that the low rates reflect clinical observations in Sweden, where the population follows public-health advice to limit pain-relief medication.

This was the state of the research debate when media stories said that Robert F. Kennedy Jr was planning to announce that paracetamol was a cause of autism. (He has since clarified that he meant a ‘causative association’, which is a weaker link than saying that it definitely causes autism.) The assertion caught researchers off guard. Although some, including Kristensen, think that paracetamol is a risk factor, they don’t use the word ‘cause’. The bar is high for researchers to say that a link is causal, say those interviewed for this article. Many hasten to clarify that an association found in studies does not yet indicate a cause-and-effect relationship.

“All the studies we evaluated were not designed to determine whether using acetaminophen causes ADHD or autism,” Prada says. “They did not ask that question, and we cannot answer it.”

“My personal view is that we are not there yet to find causality” for ADHD, says Liew. “We still need more research that considers, is it really the medication or some maternal factors that lead to use of the medication that haven’t been discovered?”

Caution and clarity

What research is needed to prove or disprove that paracetamol raises the risk of ADHD? A November 2025 review of studies published so far found that most of them failed to account for other possible risk factors by comparing children with their siblings. It rated confidence in the findings of reviews as low to critically low13, underscoring the need for more research.

One of the problems is that all the research is observational, based on following up mothers and children, rather than interventional, by assigning pregnant women to take a drug or not, which would be unethical. “We will never have that smoking gun,” says Kristensen. “We will never be able to do the intervention study that will, in humans, show the causality.”

But studies could come closer. In particular, more studies along the lines of Baker’s are needed that show levels of paracetamol in mothers and newborns, and their relationship to disorders. “I want to see more replications with larger samples,” Alwan says, adding that studies must also take into account diagnoses in the parents, as well as factors that could lead women to take paracetamol, such as illness, fever and pain. “I would definitely change my view if negative-control sibling designs, including prospectively measured exposures and parental psychiatric assessments, showed high risks,” she says.

Advice for pregnant women

Given the state of the evidence, what advice should pregnant women be given? Failing to address pain and fever, as President Donald Trump has advised, could have negative consequences. “The risks are clear and known” for fever early in pregnancy, Alwan says — mainly neural-tube defects, such as spina bifida, in the fetus. Prolonged maternal fever has also been associated with a higher risk of congenital heart defects, oral clefts, miscarriage, preterm birth and low Apgar scores, she says.

Without treatment, severe, chronic pain in pregnancy can result in depression, anxiety and high blood pressure, leading to adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preterm birth and fetal growth restriction, Alwan says. Paracetamol remains the drug of choice, she adds, because other pain and fever medications have well-established risks in pregnancy. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen, can cause miscarriage, and opioids can cause serious birth defects. Indeed, there is a strong consensus among researchers, who agree that paracetamol has a place in pregnancy for pain and fever relief, but it should be taken only when it is needed and effective, under the care of health-care professionals, such as a physician, nurse or pharmacist.

Baker argues that the guidance from government regulators should be updated to reflect the emerging research. “The guidance could be more clear and specific,” he says, especially with regard to what symptoms the drug should be taken for, because paracetamol is ineffective for many types of pain, such as lower-back pain. “The guidance out there says ‘always consult with your physician’, but I think that’s insufficient, given the reality of how people use pain and fever medications during pregnancy.”

Indeed, the US Food and Drug Administration said on 22 September that it plans to change the label for paracetamol and alert physicians to the association between paracetamol and ADHD, as well as autism, found in the research.

“While we’re waiting for more conclusive evidence or data, what can we do?” asks Liew. “We don’t want to provoke fear or anxiety, because it’s still ongoing research. But, on the other hand, we still think it’s important to advise against overuse or unnecessary use. The data might be warning us of potential harm for the long-term health of the offspring. Therefore, we should use the medication diligently if we need to use it.”