Emission estimates

So far, no atmospheric emission inventory exists that covers all known MP sources. Traffic emissions are considered one of the largest primary MP environmental sources26,27. We used the bottom-up emissions as described in ref. 24 (Supplementary Text 1), which compiles emissions from tyre wear, brake wear, road markings and road surface wear. Recently, Bucci et al.10 and Evangelou et al.11 estimated the resuspension emissions from the ocean and from bare arid soils, respectively. Both studies reported bottom-up estimates based on process modelling of the respective source. We combined the traffic, ocean and bare arid soil emissions and refer to this emission case as ‘bottom-up’ (BU). Notice that potentially important emissions are missing from this inventory (for example, emissions from clothing, industrial sources and so on). No reliable bottom-up emission estimates exist for these sources but we assume that their spatial distribution is similar to the traffic emissions. Traffic emissions may thus serve as a proxy for all primary MP emissions.

In the study of Brahney et al.20, emissions from the ocean, traffic, mineral dust, agricultural dust and population activities were estimated on the basis of proxies, such as population density, sea spray and mineral dust emissions. An atmospheric transport model was then fed with these emissions and the resulting simulated values were compared with in situ measurements of MP deposition in the western United States. The emissions were then optimized top-down. Following the study of Brahney et al., Evangeliou et al.3 presented a different top-down emission estimate using the same measurements but a different modelling and inversion approach. We refer to these two top-down (TD) emission inventories as TD-B and TD-E for Brahney et al. and Evangeliou et al., respectively.

All three emission datasets were regridded to a 0.5° × 0.5° spatial resolution. The TD-B and TD-E emission estimates are available at yearly and 6-h time resolution, respectively. BU traffic-related MP emissions are given at yearly and the oceanic and resuspension MP emissions at 6-h resolution.

The total mass emissions of each sector were weighted to the four size bins 5–10, 10–25, 25–50 and 50–100 μm used for atmospheric transport modelling (Supplementary Table 1), on the basis of one size distribution per sector (Supplementary Text 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Thus, the emission magnitude of the different emission cases can be compared, as the size distribution influence is the same for every estimate.

MP emissions are mostly reported in mass units, whereas most atmospheric MP measurements are reported as number concentrations, which requires a conversion that is sensitive to the underlying assumed size distributions. The emissions were converted from particle mass to particle number units using the geometric mean size of each size bin and assuming a spherical shape, except for the TD-E population sector, for which fibres were assumed.

Compilation of MP measurements

Measurements of atmospheric MP concentration and bulk, wet and dry deposition were collected from reports in the literature. Studies were included only if they reported the sampling location and dates, the identified particle sizes and shapes and the measured air concentration or deposition of MPs, expressed as number (or mass) per volume of air or, for deposition measurements, per m2 per sampling period or day, respectively.

The MP measurement dataset is available with information about the study (author name, year of publication, DOI), the location (longitude, latitude and, if applicable, height above sea level), time of sampling (start and end date), type of measurement (air concentration, bulk, wet or dry deposition) and measured value (in number and mass units). The shapes and sizes of the particles are also included, as well as the code of the region in which we classified the measurement (Supplementary Fig. 2) and the type of sampling region (land, coastal, sea).

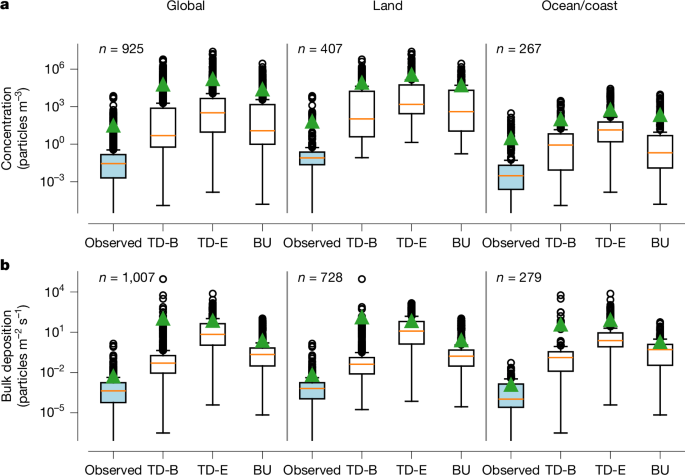

Because most studies reported the abundance of MPs in number of particles found, we converted all of the mass data values into number values (Supplementary Text 2). The resulting MP values for concentration and deposition in units of particles m−3 and particles m−2 s−1 are shown in Extended Data Fig. 1.

Source–receptor modelling

To establish quantitative relationships between the emission sources and the measured air concentrations and deposition values, we used the Lagrangian particle dispersion model FLEXPART version 11 (ref. 28). FLEXPART offers an efficient option to calculate emission sensitivities through backward-in-time calculations from the location and times of air concentration29,30 and deposition measurements31. The emission sensitivity matrices provide quantitative relationships between potential sources and measurements. When multiplied by the spatially resolved emission fluxes from the three inventories, modelled air concentrations and deposition values that correspond in space and time with the measured values can be calculated.

The model was driven with ERA5 meteorological reanalysis data32 with hourly time resolution and 0.5° × 0.5° spatial resolution with 138 vertical levels. FLEXPART accounts for in-cloud and below-cloud wet scavenging, dry deposition, as well as shape-dependent and size-dependent gravitational settling. For simulating the in-cloud scavenging, the cloud condensation nuclei and ice nuclei efficiencies were set to 0.05 and 0.15, respectively, as a base case33. Cloud condensation nuclei and ice nuclei efficiencies of 0.001 and 0.01 as well as 0.5 and 0.8 (minimum and maximum scavenging case) were also used for calculating the sensitivity of the simulation results to the wet scavenging.

For air concentration measurements, we released 100,000 virtual particles within a layer of 0–50 m above ground level at the location and time of each measurement sample (for shipboard measurements, we released at a height of 30 m). For deposition values, we traced wet and dry deposition separately backward by releasing 100,000 virtual particles within the lowest 30 m for dry deposition and 1,000,000 particles within the whole atmospheric column for wet deposition31. For total deposition, the emission sensitivity fields for dry and wet deposition were combined. We tracked the particles backward in time for at least 60 days, which corresponds to several times the expected atmospheric lifetime of micrometre-sized particles.

We simulated four particle size bins, 5–10, 10–25, 25–50 and 50–100 μm. For the simulations, we specified the shape according to the dominant shape reported by the respective experimental study or, if the percentage contribution of several shapes was reported, we weighted the measured values with the reported percentages and simulated the different shapes.

Fibres and fragments were simulated as cylinders with an aspect ratio (that is, length-to-diameter ratio) corresponding to the measurements or with an aspect ratio of 40 and 2, respectively, if no information was available. Films were simulated as square-shaped particles with a thickness (smallest dimension) of 5 μm (ref. 34). All other morphologies were assumed to be spherical. The particle density was set to 1,200 kg m−3. The simulated values were aligned to correspond with the measured size range of the respective study, using the simulated size distribution (Supplementary Text 3).

Statistics

To determine the agreement between observed and modelled values, we used the following statistical measures: the Pearson correlation coefficient (r), the fractional bias (FB), the factor of exceedance (FOEX), the root mean squared error (RMSE) and the fraction of predictions within a factor of ten of the observations (FAC10).

For N pairs of observations (\({C}_{{{\rm{o}}}_{i}}\)) and simulations (\({C}_{{{\rm{s}}}_{i}}\)), the statistical measures are defined as:

$$r=\frac{{\sum }_{i=1}^{N}({C}_{{{\rm{s}}}_{i}}-\overline{{C}_{{\rm{s}}}})({C}_{{{\rm{o}}}_{i}}-\overline{{C}_{{\rm{o}}}})}{\sqrt{{\sum }_{i=1}^{N}{({C}_{{{\rm{s}}}_{i}}-\overline{{C}_{{\rm{s}}}})}^{2}{\sum }_{i=1}^{N}{({C}_{{{\rm{o}}}_{i}}-\overline{{C}_{{\rm{o}}}})}^{2}}}$$

(1)

$${\rm{FB}}=\frac{2}{N}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{N}\frac{({C}_{{{\rm{s}}}_{i}}-{C}_{{{\rm{o}}}_{i}})}{({C}_{{{\rm{s}}}_{i}}+{C}_{{{\rm{o}}}_{i}})}$$

(2)

$${\rm{FOEX}}\,( \% )=\left[\frac{N({C}_{{{\rm{s}}}_{i}} > {C}_{{{\rm{o}}}_{i}})}{N}-0.5\right]\times 100$$

(3)

$${\rm{RMSE}}=\sqrt{\frac{{\sum }_{i=1}^{N}{({C}_{{{\rm{s}}}_{i}}-{C}_{{{\rm{o}}}_{i}})}^{2}}{N}}$$

(4)

FAC10 is defined as the fraction of data for which:

$$0.1\le \frac{{C}_{{{\rm{s}}}_{i}}}{{C}_{{{\rm{o}}}_{i}}}\le 10.0$$

(5)

in which \(\overline{{C}_{{\rm{o}}}}\) is the mean of the observed values, \(\overline{{C}_{{\rm{s}}}}\) is the mean of the simulated values and N(\({C}_{{{\rm{s}}}_{i}}\) > \({C}_{{{\rm{o}}}_{i}}\)) is the number of overpredictions. It is true that r ∈ [−1, 1], FB ∈ [−2, 2], FOEX ∈ [−50%, 50%] and RMSE ∈ [0, ∞].

The Pearson correlation coefficient r measures the linear correlation between the observed and simulated values. The FB evaluates the mean relative difference between predicted and observed values and is bounded between −2 and 2, with 0 indicating no bias. FOEX shows whether a model tends to overpredict or underpredict the measurements. A FOEX value equal to −50% means that all of the values are underpredicted, whereas a value of 50% shows that all of the values are overpredicted. RMSE is a variation metric, and a value of 0 would indicate a perfect fit to the data. FAC10 gives the fraction of simulated values that are within a factor of 10 of the observed values.

Emission scaling

Because observed median MP concentrations over the ocean are only 4% (3%–6%) of those over land, measurements over land are unlikely to be strongly influenced by the advection of oceanic MPs. Therefore, we first scale the terrestrial emissions such that the mean modelled and observed concentrations over land are identical and subsequently scale the oceanic emissions in the same way but using only observations that are not heavily influenced by the land emissions.

We determined the ratio R of observed and BU-model-simulated mean atmospheric concentrations over land (n = 407; Supplementary Fig. 4):

$$R=\frac{\overline{\,{{\rm{o}}{\rm{b}}{\rm{s}}}_{{\rm{l}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{d}}}}}{\overline{\,{{\rm{s}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{m}}}_{{\rm{l}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{d}}}}}$$

(6)

in which \(\overline{{{\rm{obs}}}_{{\rm{land}}}}\) and \(\overline{{{\rm{sim}}}_{{\rm{land}}}}\) are the mean observed and simulated values, respectively. Subsequently, we scaled the sum of the terrestrial BU emissions with R, while preserving the BU emission spatial distribution. This way, we avoid artificially reducing uncertainties in regions lacking observations. A 90% two-sided confidence interval was derived for the emission scaling factor based on error propagation of the underlying uncertainties of the ratio (Supplementary Text 4).

Using the scaled terrestrial emissions, we simulated again the concentrations over the ocean using BU emissions and identified the measurement samples in which the oceanic MP contribution was larger than the scaled terrestrial contribution (that is, oceanic contribution larger than 50%). This left 33 measurements over the open ocean (Supplementary Fig. 4). We then subtracted the modelled terrestrial contribution from the measurements and scaled the oceanic BU emissions with the ratio of the mean measurement residual and the modelled oceanic contribution. The uncertainty of the oceanic scaling factor was calculated in the same way as for land. Notice that the relative uncertainty of the scaling factor is larger for the ocean than for land, owing to the smaller sample size and sparser spatial coverage. The difference in our scaled emissions compared with previous studies3,20 originates primarily from our much larger and globally more representative measurement dataset, including many measurements from East Asia and over the ocean. In fact, the mean modelled oceanic emission contribution to the measurement locations used in Brahney et al.20 and Evangeliou et al.3 is minor (3% and 0.25% for TD-B and TD-E emission cases, respectively). This indicates that these measurements made in the continental interior are not sufficient to constrain the oceanic MP source and that MP measurements over the open sea are necessary. Further reasons for the difference in our scaled emissions are methodological differences and our alignment of measured and modelled size distributions.