Cohort description and recruitment

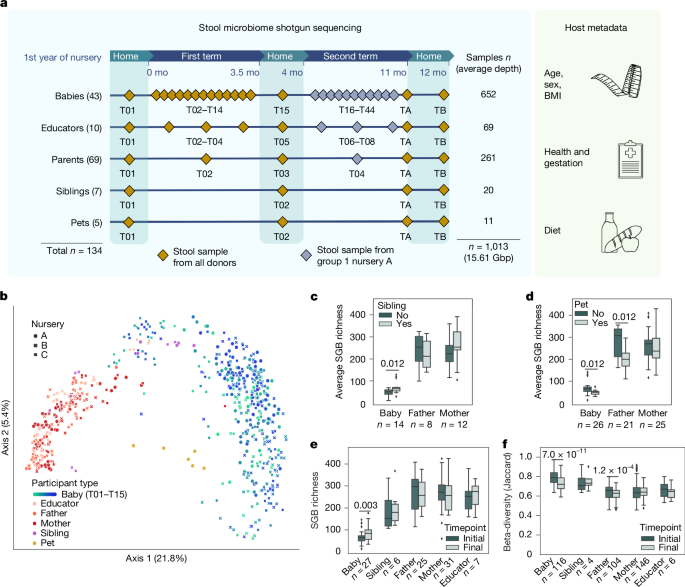

A total of 134 volunteers comprising babies (4–15 months old at nursery start, median 10 months, 18 male, 25 female) about to attend the first year of nursery school, their parents (29–50 years old, median 36 years old, 30 male, 39 female), siblings (2–21 years old, median 2 years old, 3 male, 4 female) and house pets (n = 5, 2 cats and 3 dogs), and educators (34–56 years old, median 38.5 years old, 10 female) were recruited and enroled across 3 nursery schools (here identified as A, B and C), each with 2 distinct classes, in the municipality of Trento (Italy) in June 2022. The classes within the same nursery shared few activities (that is, baby drop-off and pick-up) and spaces throughout the day, and were followed by different educators. The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Trento (protocol number 2022-040) and by the Ethics Panel of the European Research Council Executive Agency after evaluation of the project (microTOUCH Grant agreement ID 101045015). Upon enrolment, volunteers were asked to provide informed consent and complete metadata questionnaires. Consent for participation of babies was obtained directly from parents.

Metadata collection and organization

Date of birth, sex, anthropometric data (weight, height), and antibiotic treatment in the 3 months preceding the start of the study or supplemented during its course, in addition to information regarding putative contacts with other volunteers preceding the beginning of nursery, were collected for volunteers of all ages. Metadata specifically collected for babies included gestation length, mode of delivery and general diet at nursery admission (breast or formula milk feeding and weaning date of start). Adult participants were also required to provide information regarding past or ongoing chronic conditions and relative treatments, and putative maternal anti-Streptococcus B prophylaxis during birth. Diet metadata for babies and adults are detailed in the next section.

Dietary information collection and analysis

In brief, most babies had begun weaning at T01 (weaned n = 38, not weaned n = 2, not available = 3) and received identical solid meals while in the nursery. The majority followed a mixed feeding approach during weaning, combining solid foods with any type of milk (mixed diet n = 24, exclusively solid food n = 14, not available = 5). Among those babies receiving milk supplementation, feeding types were relatively balanced (breast-fed n = 9, formula-fed n = 10, receiving both n = 5). Finally, adults detailed their long-term dietary habits via the compilation of the EPIC Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ). FFQs were used to calculate the healthy Plant-based Diet Index65. Quality and quantity of plant-based foods were derived from FFQs for a total of 18 food groups, and divided into quintiles and assigned positive or negative scores. Participants whose intake exceeded the highest quintile received a score of 5, whereas those below the lowest quintile received a score of 1. Healthy plant-based foods received positive scores, whereas less healthy or unhealthy plant-based and animal-based foods received a negative score. A final score was derived by summarizing the scores of each participant. Metadata were collected and utilized after pseudonymization of volunteers IDs.

Sample collection

Sample collection began a week before the start of the first term of nursery (August 2022) and ended after the Christmas holidays (January 2023) for all volunteers. During the first 2 weeks the nursery organized a ‘settling-in phase’, in which babies were gradually introduced to the nursery and attended it for about 3 hours per weekday. In the following weeks, babies attended the nursery for about 8 hours per weekday. Throughout the term length (about 14 weeks), stool samples of infant participants were collected weekly (from before nursery admission T01 to at the end of Christmas holidays T15) by the nursery staff or the researcher in the nursery from nappies stored at room temperature on the same day of use, using collection tubes for specimen collection containing 9 ml of DNA/RNA Shield buffer (Zymo). Sample collection was extended until the end of the second term of the year (about 30 weeks, ending July 2023) for all donors in group 1 of nursery A, including babies, parents, educators and pets, maintaining sampling time-point frequencies and modalities. Two follow-up time points were collected for all participants enroled, at the end of the year of nursery (July 2023, ‘TA’) and at the end of the summer break (August/September 2023, ‘TB’). The samples collected were moved to the lab and DNA-extracted within 2 weeks of delivery. Samples collection of babies during summer or winter breaks time points together with those of siblings and pets were performed directly at home by the parents and stored at room temperature until the beginning of nursery (maximum 2 weeks later). All adult participants’ samples were self-collected following detailed instructions, delivered to the lab and processed as previously. Educators donated monthly, whereas parents collected one additional sample halfway the study period, in addition to initial and final sample time points.

DNA extraction and sequencing

After vortex homogenization, DNA was extracted using the DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (Qiagen), following the directions of the Human Microbiome Project protocol66. Additional homogenized aliquots were stored at −20 °C. DNA was quantified using Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Sequencing libraries were prepared using the Nextera DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina), as described by the manufacturer’s guidelines. The sequencing was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform following manufacturer’s protocols. The sequencing depth was set at 15 Gbp.

Metagenome quality control and preprocessing

Stool samples sequences were pre-processed using the pipeline described at https://github.com/SegataLab/preprocessing. In brief, metagenomic reads were quality-controlled and reads of low quality (quality score <Q20), short reads (<75 bp) and reads with >2 ambiguous nucleotides were removed with Trim Galore (v0.6.6). Contaminant and host DNA was identified with Bowtie2 (v2.3.4.3)67 using the -sensitive-local parameter, allowing confident removal of the phiX 174 Illumina spike-in and human-associated reads (hg19/GRCh37 human genome release). Remaining high-quality reads were sorted and split to create standard forward, reverse and unpaired reads output files for each metagenome. Metagenomes with at least 1 Gbp were included in the analysis (n = 1,021), whereas metagenomes with insufficient sequencing depth were excluded (n = 5).

Species-level profiling

Profiling at the resolution of SGBs was performed with MetaPhlAn (v4.1)16,68 using the vJun23_202307 markers database and using the –unclassified_estimation parameter (Supplementary Table 4). SGBs with <0.1% relative abundance in all stool samples were removed from taxonomic profiles for calculation of diversity indices.

Building strain-level phylogenetic trees

To reliably detect strain-sharing events, we augmented our dataset with oral samples from the same cohort not analysed in this study (n = 342) and additional samples from 16 public longitudinal cohorts. To do so, we queried the curatedMetagenomicData (v3.18)69 for stool samples sequenced at least at 1-Gbp depth from healthy westernized human individuals with at least 2 time points per individual and 3 such individuals per dataset. We went through the corresponding papers and excluded studies involving an intervention between the sampled time points. Thus we have included samples satisfying the above criteria from the following datasets: ShaoY_2019 (ref. 32), MehtaRS_2018 (ref. 70), VatanenT_2016 (ref. 71), HMP_2019_ibdmdb72,73, BackhedF_2015 (ref. 74), CosteaPI_2017 (ref. 75), YassourM_2018 (ref. 3), KosticAD_2015 (ref. 76), LouisS_2016 (ref. 77), FerrettiP_2018 (ref. 1), HallAB_2017 (ref. 78), WampachL_2018 (ref. 79), NielsenHB_2014 (ref. 80), Heitz-BuschartA_2016 (ref. 81), ChuDM_2017 (ref. 82) and AsnicarF_2017 (ref. 83). In total, phylogenetic trees were built using data from 1,405 samples from this cohort and 4,322 samples from additional cohorts.

For all the SGBs detected in our cohort, we queried MetaRefSGB, a microbial genomic database containing >156,000 isolate genomes and >952,000 metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) as of vJun23 (ref. 16), for isolate genomes or MAGs from food sources, and included them in the trees as references84.

To build each tree, we included all the samples for which the SGB was detected by MetaPhlAn. SGBs detected in less than 20 samples from our cohort were discarded, leaving 1,363 SGBs. The strain-level phylogenetic trees were built for each SGB with StrainPhlAn (v4.1)16,68. For 1,107 SGBs, we were able to build the phylogenetic tree; the remaining 256 SGBs did not have a sufficient number of samples with enough marker genes with minimal coverage as reported by StrainPhlAn.

Assessment of SSRs

We discarded trees built from alignments shorter than 1,000 nt (n = 111 SGBs discarded). In the phylogenetic trees with genomes from a food source, we considered the ANI on the marker genes (mutation rates in StrainPhlAn) and discarded samples closer than 99.85% ANI as probably coming from food. When more than 20% of the samples would be discarded, we dropped the SGB altogether (n = 7 SGBs discarded).

We calculated phylogenetic distances between all samples as the length of the shortest path between the samples along the tree branches. We normalized distance distributions within each tree by dividing by the median distance.

To define strain-sharing events, we calculated a threshold best separating the within-individual distribution from the across-individuals distribution of phylogenetic distances. For the within-individual distribution, pairs of samples from the same individual sampled maximum 6 months apart were considered using maximum one pair per individual. Among the possible pairs, we chose the one maximizing the chances to type the strain of the SGB of interest in both samples, and we did so by choosing the pair for which the sample with the lowest coverage for the SGB between the two samples was the highest among all pairs. In case of ties, we maximized the higher estimated coverage of the two. The SGB coverage was estimated as the sequencing depth times the SGB’s relative abundance. For the across-individuals distribution, we pick pairs of samples coming from different datasets, one sample per individual maximizing the coverage. When there were less than 50 pairs in the across-individual distribution we discarded the SGB (n = 365 SGBs discarded). When there were less than 20 pairs in the within-individual distribution (n = 276 SGBs), we calculated the threshold as the 3rd percentile of the across-individual distribution, that is, setting the expected false discovery rate to 3%. When the within-individual distribution had at least 20 pairs (n = 309 SGBs), the threshold separating the distributions was calculated as maximizing Youden’s index, unless the expected false discovery rate exceeded 5%, in which case we set the threshold as the 5th percentile of the across-individual distribution (n = 61 SGBs). After manual curation of the trees, including outlier branches removal, a further 112 SGBs were discarded. In total, we assessed strain-sharing for 512 SGBs.

For each pair of samples, we called a strain-sharing event of an SGB when their phylogenetic distance in the corresponding tree was lower than the corresponding calculated threshold.

For each sample, we considered the SGBs in which corresponding trees it was placed, that is, profiled by StrainPhlAn. Finally, we define the SSR as the number of strain-sharing events divided by the number of SGBs profiled at the strain level in both of them by StrainPhlAn. For pairs with less than five SGBs profiled in common, we set the SSR as undefined and such pairs were excluded from SSR analysis. Strain retention rate is defined as the within-individual SSR. The within-individual strain replacement rate is defined as the number of strains not retained longitudinally among retained SGBs over the number of retained SGBs.

Samples found to be contaminated or mislabelled according to strain-sharing analysis (and validated with CrocoDeEL (v1.0.6)85) were removed post hoc (n = 8), reducing the dataset to 1,013 metagenomes. Samples collected during antibiotic treatment (n = 26) were excluded from all following analyses.

Within-SGB strain heterogeneity, strain-sharing networks and SGB transmissibility

Within-SGB strain heterogeneity (Extended Data Fig. 7a) was computed on a per-nursery basis as the number of strains of a given SGB present among babies at a given time point over the number of babies having the SGB at the same time point. A within-SGB strain heterogeneity of 1 indicates there is no strain-sharing among babies having the SGB (that is, they all have a different strain of the SGB).

Strain-sharing matrices were used to build unsupervised strain-sharing networks (Fig. 3b) with the R packages ggraph (v2.2.1) and tidygraph (v1.3.1), where only nodes with degree >0 are shown.

SGB transmissibility (Extended Data Fig. 9a) was computed as the number of individual pairs sharing the strain over the total number of potentially callable strain-sharing events involving the SGB (that is, the number of pairs of individuals in which the SGB was present and typable according to StrainPhlAn)8. When the SGB was not present among at least three pairs within a category, the transmissibility of the SGB within the category was set as undefined. Differential transmissibility between baby–baby and baby–mother or baby–father pairs was assessed for all SGBs having at least 10 baby–baby pairs sharing it, with application of a Fisher’s exact test (including false discovery rate control) in case there were at least 10 baby–mother pairs or 10 baby–father pairs sharing the SGB; otherwise the number of SGB- and strain-sharing events were reported for each group without application of the test.

Comparison of the contribution of familial and nursery strains with the infant microbiome

To compare the contribution of familial and nursery strains to babies’ microbiome composition, for each baby, we computed at each baby time point (T01 to T15) the number of strains shared either with any member of the family or with any other infant of the nursery group, disregarding strains shared with both (unless otherwise stated). This allowed us to compute the proportion of strains for a given baby microbiome that was putatively acquired from either the nursery or family (referred to in the text and figures as the ‘proportion of strains acquired’), as the strains exclusively shared with either one of the two groups of individuals. Considering that family members were less densely sampled than infants, we considered a maximum of three samples for each of the other babies in the nursery group (baseline T01, halftime T08 and final T15, when available, emulating the sampling timeline of parents), adding other babies and family samples to the longitudinal analysis considering the time in which they were sampled (that is, looking for strain-sharing only with samples collected in the past or contemporaneous to the target time point of the target baby). This probably explains the nonlinear increases of proportion of strains acquired from the nursery group at baby T08 and T15 observed (for example, Fig. 4c). Moreover, as a negative control for the considerably larger number of individuals in the nursery group (average n = 7) compared with the family (average n = 2), we also analysed the strain-sharing dynamics with a random nursery group from another nursery.

Metagenomic assembly and CRISPR analysis

MAGs were generated through a previously validated metagenomic assembly pipeline17, including assembly of contigs with MEGAHIT (v1.1.1)86, calculation of contigs coverage with Bowtie2 (v2.2.9)67, binning of contigs with MetaBAT2 (v2.12.1)87 and quality-checking of bins with CheckM (v1.1.3)88. Medium- and high-quality MAGs were identified following the criteria previously proposed89 and low-quality MAGs were discarded. The ANI between MAGs was computed using skani (v.0.2.1)90.

To validate the chain of transmission events of the strain of A. muciniphila SGB9226 shown in Fig. 2a, CRISPR arrays were identified from MAGs using MinCED (v0.4.2, default parameters)91. CRISPR spacers and repeats were extracted from raw sequencing reads using Crass (v1.0.1, parameters -d 20 -D 55 -s 20 -S 55 –longDescription)92. Following the identification of 5 CRISPR arrays and 39 CRISPR spacers in this set of MAGs, we looked for the CRISPR spacers of this strain in the metagenomic reads of the whole dataset. Although single CRISPR spacers were found in the metagenomic reads of up to 16/19 samples containing the strain (Fig. 2a), none of the 39 CRISPR spacers could ever be found in the remaining 627 metagenomes, providing independent validation for the trajectory of the strain in the nursery group.

B. longum strains assignment to subspecies

To evaluate the transmissibility of distinct subspecies of B. longum SGB17248 in our dataset, we constructed a StrainPhlAn 4 phylogenetic tree of all 591 B. longum strains identified in our cohort, which revealed 2 distinct clusters (cluster_1 and cluster_2; Extended Data Fig. 10c–e). Cluster_1 consisted exclusively of strains present in babies and hence was hypothesized to belong to B. longum subsp. infantis, whereas cluster_2 contained strains from both babies and adults, possibly representing other subspecies of B. longum. To definitively assign these strains to subspecies, we succeeded in generating MAGs (as described above) for 262 of the 591 strains and then calculated the ANI between these MAGs and 15 reference genomes representing the 3 well-known B. longum subspecies93 (5 reference genomes each for subsp. longum, subsp. infantis and subsp. suis). The 24 MAGs from cluster_1 showed highest similarity to B. longum subsp. infantis reference genomes (median ANI 98.04%), compared with lower ANI values with subsp. longum (95.60%) and subsp. suis (96.13%). Conversely, the 238 MAGs from cluster_2 showed the highest genomic similarity to B. longum subsp. longum reference genomes (median ANI 98.87%), with substantially lower similarity to subsp. suis (96.82%) and subsp. infantis (95.39%). The 591 B. longum strains as profiled with StrainPhlAn 4 were then assigned according to their genome-level assignment.

Blastocystis detection and ST profiling

The presence of Blastocystis in metagenomic samples was assessed using a previously validated computational workflow94. In brief, nine reference genomes for eight distinct Blastocystis subtypes (that is, subtype 1 (ST1) (ST1_LXWW01), ST2 (ST2_JZRJ01), ST3 (ST3_JZRK01), ST4 (GCF_000743755 and ST4_BT1_JZRL01), ST6 (ST6_JZRM01), ST8 (ST8_JZRN01) and ST9 (ST9_JZRO01)) were mapped against metagenomic reads with Bowtie2 (v2.5). Then, SAMtools (v1.19) and bedtools (v2.30) were used to compute the breadth of coverage of each genome. We reported a sample to be positive for a Blastocystis ST if the respective genome had a breadth of coverage of at least 10%.

PCR validation of transmission of an A. muciniphila SGB9226 strain

To further test how much potential problems with limit of detection in the metagenomic approach could influence strain transmission inference, we implemented an SGB-specific PCR assay for A. muciniphila (SGB9226) and applied it to the representative example depicted in Fig. 2a. We designed the primers (F-5′-TGACTGGACTCTATTGCCTGAAG-3′ and R-5′-GCCTTTCAATATGCCCTTCGTAC-3′; amplicon length 101 bp) to recognize the SGB9226-specific core gene (UniRef90_A0A2N8IRV1; identified by MetaPhlAn 4 (ref. 16)), using ConsensusPrime (v.1.0, with set consensus similarity 0.8 and consensus threshold 0.95)95 and Primer3 (v. 2.6.1; with set primer size 18–28 bp, optimal melting temperature 57–63 °C, GC content 40–60%, PRIMER_MAX_HAIRPIN_TH 24.0, PRIMER_INTERNAL_MAX_HAIRPIN_TH 24.0, PRIMER_MAX_END_STABILITA 9.0)96. Assay sensitivity was independently evaluated using a spike-in approach with DNA from the A. muciniphila type strain ATCC BAA-835 (from 1 M down to 1 single genome copy) into an A. muciniphila-negative faecal test sample. The assay achieved a limit of detection equivalent to a single genome copy of A. muciniphila (Extended Data Fig. 6a). PCRs were performed using GoTaq G2 Hot Start Green Master Mix (Promega) with 500 nM of each primer. The thermal cycling programme included an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of annealing at 62 °C. Positive bands were observed by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in Python (v3.10.12) using libraries scikit-bio (v0.5.9), scipy (v1.10.1) and statsmodels (v0.14.0). Cross-sectional comparisons between groups were performed using the Mann–Whitney U-test (two groups) or the Kruskal–Wallis test with post hoc Dunn tests (multiple groups) for independent observations. Cross-sectional dependent observations were compared with a permutation test for medians (or means, when comparing the number of shared strains), with P values calculated as the proportion of times (out of a 1,000 permutations) that the observed difference in the median between groups with shuffled labels is equal or more extreme than the observed in the correctly labelled data. Longitudinal comparisons between time points were performed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Jaccard dissimilarity matrices were computed from taxonomic profiles and compositional differences between groups were evaluated using permutational multivariate analysis of variance. When appropriate, correction for multiple testing was applied using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure (Padj), with significance defined as Padj < 0.05.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.