From quantum computing and mRNA therapeutics to artificial-intelligence-powered climate modelling, here are seven technologies that Nature will be keeping its eye on.

Xenotransplantation

Every day, around two dozen people die awaiting an organ transplant in the 46 countries of the Council of Europe, together with 13 in the United States. The real toll might be higher still: according to Alexandre Loupy, a nephrologist at Necker Hospital in Paris, “many patients with terminal organ failure are not even wait-listed”.

AI and nuclear energy feature strongly in agenda-setting technologies for 2026

Xenotransplantation — replacing damaged human tissues with counterparts from closely related animal species — offers a tantalizing alternative to precious human organs. But such transplants tend to fail quickly, with the remarkable exception of one woman who survived nine months after receiving a chimpanzee kidney in 1964.

The problem is immune rejection. Pig cells, for instance, are coated with a carbohydrate, called alpha-gal, that triggers a strong immune reaction in humans, who lack this molecule. Precision genome editing with CRISPR–Cas9 has given scientists an effective tool for eliminating this and other sources of rejection and, in combination with next-generation immunosuppressants, this tool is hugely improving patient outcomes.

In 2024, clinicians at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston teamed up with xenotransplantation company eGenesis in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to perform the first transplant of a pig kidney into a living person1. The kidney came from an animal with 69 genomic modifications to knock out immunity-triggering antigens and dormant viral sequences while also inserting human genes that reduce inflammation and prevent abnormal blood clotting. The patient survived for 52 days before dying from unrelated cardiac issues. Subsequent pig-kidney recipients in the United States and China remained stable for more than eight months before returning to dialysis — nearly matching 1964’s durability record.

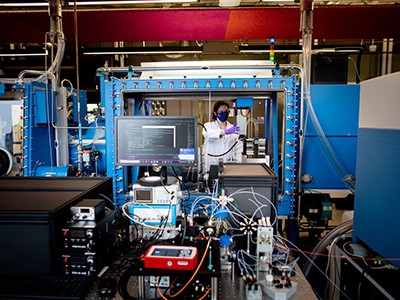

The first transplant of an engineered pig heart into a person, in 2022.Credit: University Of Maryland School Of Medicine/ZUMA/Alamy

And it’s not just kidneys. In 2022, Muhammad Mohiuddin, a surgeon at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore, and his colleagues described the first transplant of an engineered pig heart into a person, who survived for 60 days after surgery2. And in 2025, teams in China reported xenotransplantation of pig liver3 and even lung4 into people who had been declared brain dead — a key step towards working with recipients capable of recovery.

Even a transient xenograft could buy precious time for patients awaiting a human donor, but with a deeper understanding of individual determinants of transplant rejection, these substitutes could become a long-term solution, says Leonardo Riella, chair of transplantation at Massachusetts General Hospital and one of the leads on the 2024 kidney transplant. “The xenotransplant really permits us to think outside the box and personalize that kidney and make it invisible to your immune system,” he says.

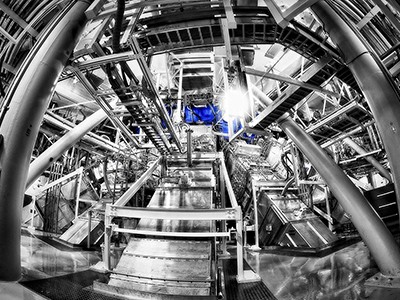

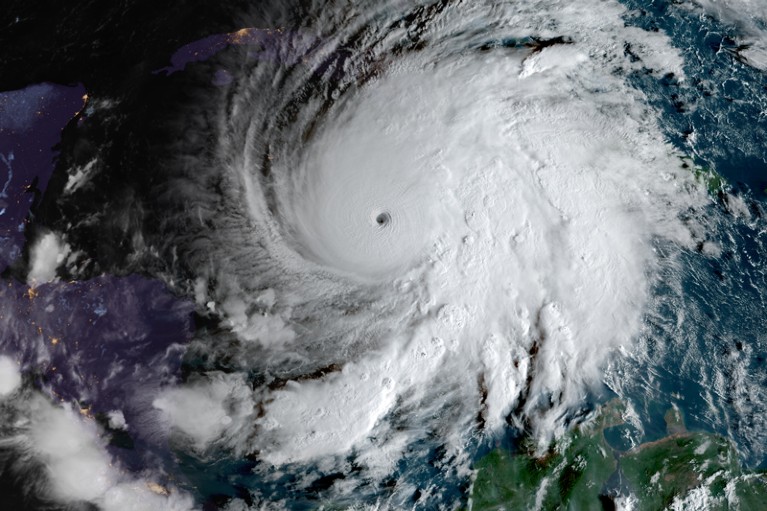

AI-powered meteorology

In October 2025, an AI model from Google DeepMind in London gave the US National Hurricane Center an early warning about the serious threat posed by Hurricane Melissa. The model anticipated the storm’s evolution to category-5 intensity days in advance and accurately predicted its trajectory across the Caribbean, whereas older models fell short.

Self-driving laboratories, advanced immunotherapies and five more technologies to watch in 2025

That success is just one example of how AI methods are accelerating and improving local weather forecasting, storm tracking and even global climate modelling, with ever-more-sophisticated models rapidly emerging.

In some ways, this is an ideal arena for AI. Earth and atmospheric researchers have tons of data at their fingertips. But wrangling those data into a forecast has historically relied on using sophisticated and computationally intensive numerical weather-prediction models to crunch through complex differential equations. “They involve literally millions of lines of code and a large team to run them,” says Richard Turner, a machine-learning researcher at the University of Cambridge, UK. But over the past three years, promising AI models have begun to emerge, including Pangu-Weather, from Huawei Cloud in Shenzhen, China, which used deep learning to accelerate forecasting up to 10,000-fold relative to existing methods5.

AI models are advancing weather forecasting.Credit: CSU/CIRA & NOAA

Most models tackle only part of the forecasting workflow. But in 2025, Turner and his colleagues published Aardvark, an ‘end-to-end’ model6 that was trained to ingest raw data from sources including weather stations and satellites, and deliver localized forecasts up to ten days ahead. “We could literally run it off a desktop machine in an office,” says Turner, who notes that Aardvark’s accuracy was competitive with existing systems, and occasionally outperformed them.

Turner has also collaborated with Microsoft Research in Amsterdam to develop an AI ‘foundation model’ called Aurora, which could accurately predict meteorological events that fall beyond standard weather forecasts, such as cyclone trajectories and air-quality trends7.

Other AI models are even more ambitious, incorporating global insights from Earth features such as the atmosphere, sea and polar ice to analyse the current climate and predict future changes. For example, in September, engineer James Duncan at the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence in Seattle, Washington, and his colleagues described SamudrACE, which integrates AI models of the atmosphere and ocean and can simulate the behaviour of those systems over more than a millennium8.

AI models put simulation projects that were previously limited to supercomputing facilities into the hands of everyday researchers, says Elizabeth Barnes, an environmental data scientist at Boston University, Massachusetts. “All these science questions I used to have to pass off to other groups, I can do myself now,” she says.

Next-generation nuclear power

Surging investment in AI is creating a commensurate spike in demand for electrical power. The International Energy Agency in Paris predicts that global energy demand from data centres could increase by 15% annually between now and 2030.

Even if the AI boom goes bust, there remains an urgent need to bolster energy grids with climate-friendly power sources, says Jonas Kristiansen Nøland, an energy-systems researcher at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim.

These conditions present a ripe opportunity for the resurgence of nuclear energy, and Nøland is particularly optimistic about small modular reactors (SMRs) — nuclear facilities that produce up to 500 megawatts of power. That’s less than half the output of a standard fission reactor, but sufficient to power hundreds of thousands of homes.

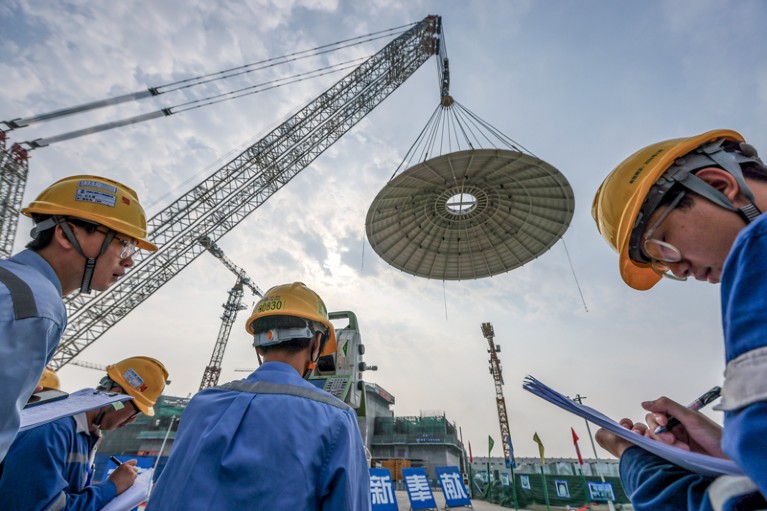

Small Modular Reactors, such as the Linglong One in China, offer a low-cost, fast-to-build option for nuclear energy generation.Credit: Luo Yunfei/China News Service/VCG/Getty

Russia and China already have active SMRs, and at least 100 projects are now under consideration or development worldwide. The most advanced — including one at Canada’s Darlington nuclear facility in Ontario, scheduled to come online in 2029 — are based on similar designs as full-scale fission reactors. But next-generation systems are also under development. Nuclear-power company TerraPower in Bellevue, Washington, for example, is pursuing molten-salt reactors, a fuel-efficient design that could greatly reduce nuclear waste and store heat produced during reactor operation for later use as thermal power.

Meanwhile, after decades of hype as the ‘technology of the future’, fusion power is nearing reality. In 2022, the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory achieved the first demonstration of net energy production from fusion at its National Ignition Facility in Livermore, California. And in 2023, the Joint European Torus near Oxford, UK, set a world record for power production, generating enough energy in five seconds to power 12,000 homes. Meanwhile, Germany’s Wendelstein 7-X facility in Greifswald achieved an endurance record of 43 seconds of sustained operation, showcasing an alternative reactor design that could enable more stable operation than first-generation ‘tokamak’ designs.

US nuclear-fusion lab enters new era: achieving ‘ignition’ over and over

Sibylle Günter, a physicist at the Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics in Garching, Germany, says that these developments are particularly exciting for countries that crave clean energy but are reluctant to engage with nuclear fission — including Germany, which plans to invest €2 billion (US$2.3 billion) in fusion by 2029. She notes that more than 50 fusion-oriented start-up companies are active worldwide, including Commonwealth Fusion Systems in Devens, Massachusetts, which aims to complete construction of a demonstration reactor this year.

Still, the world won’t be running on fusion any time soon. Between fuel production and regulatory and engineering challenges, it could be 20 years before the first commercial reactors come online, Günter notes. But balanced against cheap, safe and abundant power, she says, “20 years is not long”.

Light-microscopy brain mapping

With its capacity to image molecular-scale details precisely, electron microscopy has been the tool of choice for mapping the labyrinthine circuitry of the mammalian brain. Reconstructions of cubic-millimetre-scale volumes of mouse and human brains published in 2024 by the Machine Intelligence from Cortical Networks (MICrONS) consortium and a collaborative effort between Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Google Research in Mountain View, California, respectively (see go.nature.com/4pI6dpe), offer clear testament to electron microscopy’s utility as a powerful tool for connectomics.

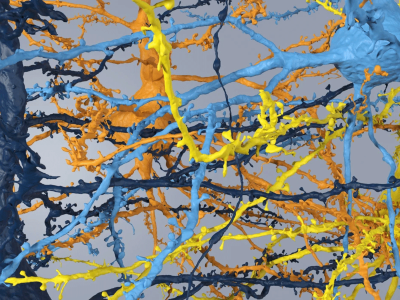

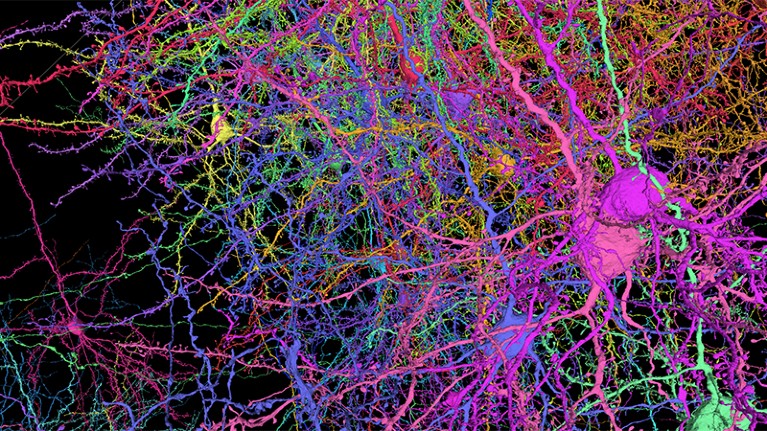

Neural connections can be imaged precisely.Credit: Allen Institute

But it’s one thing to map connectivity, and another to interpret it. “You need to differentiate which cells and synapses are there,” says Johann Danzl, an imaging specialist at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria in Klosterneuburg. “Are they excitatory? Are they inhibitory? And then — going more into depth — which types of neurotransmitters are there?”

In May 2025, Danzl’s team described a method for extracting such information. In light-microscopy-based connectomics (LICONN)9, brain samples are subjected to multiple rounds of expansion microscopy — a process in which tissue is chemically trapped in a hydrogel that expands evenly in all directions, separating the sample’s constituent biomolecules and rendering it transparent. Using protein-specific labels, researchers can visualize nanoscale details of cellular structure and organization with a standard confocal microscope while preserving the tissue’s underlying organization. In this way, Danzl’s team could map the twisty trails of axons and dendrites, as well as categorizing the synapses that they form and classifying the cells involved.

E11 Bio, a non-profit company in Alameda, California, focused on optical connectomics, has addressed another pain point for electron-microscopy-based mapping: proofreading. “If you look at that MICrONS volume, it’s beautiful,” says Andrew Payne, the company’s co-founder and chief executive. But only about “1% of the cells were ultimately reconstructed; the other 99% are not reconstructed to this day”.

A milestone map of mouse-brain connectivity reveals challenging new terrain for scientists

In a preprint from September 2025, Payne and his colleagues describe an approach in which they genetically modified mouse neurons to express various combinations of short protein epitopes, such that each cell displays a distinct barcode10. These barcodes can then be decoded by sequential staining with fluorescently labelled antibodies, enabling essentially error-free computational mapping and tracing of each neuron in the sample. Using 18 epitopes, the company could resolve some 262,000 barcodes, and Payne says that the technology should be sufficiently scalable to map connectivity across the entire mouse brain.

It’ll take other advances to make that goal practical, Danzl notes, including more-efficient sample handling and faster imaging. But by slashing proofreading expenses and replacing pricey electron microscopes with readily available confocals, these methods could put mammalian connectomes in closer reach.

Exploring the extremes

Scientists excel at discovering limits — and then pushing beyond them.

First images from world’s largest digital camera leave astronomers in awe

Last June, the US National Science Foundation and Department of Energy released early images from the Vera C. Rubin Observatory. Named after the US astronomer who first provided proof of the existence of dark matter, this groundbreaking facility in the Chilean Andes will, over a ten-year span, collect measurements from each point in the southern sky roughly 800 times. Making use of an innovative multi-mirror design and a massive 3.2 gigapixel digital camera, that scan will yield an authoritative catalogue of celestial objects and how they change over time. “We estimate we’ll have about 20 billion galaxies and close to that number of stars,” says Željko Ivezić, an astrophysicist at the University of Washington in Seattle. “We’ll have more celestial objects catalogued than living people on Earth, and for each of them, we will measure many parameters.”

Thousands of scientists from more than 30 countries have already queued up to use the observatory’s data, which should start rolling out in early 2028. Ivezić anticipates that the facility will tackle questions ranging from surveying asteroids that pose a potential threat to Earth, to proving (or rejecting) the existence of the enigmatic ‘dark energy’ that astronomers have implicated in the accelerating expansion of the Universe.