Michael Levin had just started working as a paediatric infectious-disease doctor in London when he received an urgent call from a hospital in Malta. It was the early 1980s, and a young boy had been brought in with symptoms of a severe infection that was spreading through his body, damaging multiple organs and tissues. But his doctors could find no trace of a pathogen.

The ghost of influenza past and the hunt for a universal vaccine

The boy was flown to Levin’s hospital for further tests. To the surprise of Levin and his colleagues, the culprit was a common bacterium: Mycobacterium fortuitum, which lives in water and soil, and is usually harmless. “Everyone’s exposed to them, but almost no one gets ill,” says Levin, who is now at Imperial College London. Despite aggressive treatment, the boy eventually passed away.

This case illustrates a question that has plagued doctors for decades: why do some people become severely ill from infections that leave others unscathed? What is it about some people’s immune systems that makes them susceptible? And how might these variations affect how doctors try to prevent or treat disease?

As it turned out, the boy from Malta had a brother and a cousin who had also fallen severely ill with mycobacteria infections. After years of searching, Levin and his colleagues eventually identified what made these children so sick: a genetic mutation affecting a receptor for interferon-γ, an immune molecule with myriad functions, including regulating inflammation1. Not long after that, a group in France discovered that similar mutations were responsible for rare cases of severe disease caused by another mycobacterial species — this time, a weakened form used as a tuberculosis vaccine2.

Researchers have since amassed a broad library of mutations in hundreds of genes that underlie ‘inborn errors of immunity’ (IEIs) and that make millions of people around the world susceptible to a wide range of infectious diseases and immune-linked ailments that many people can simply shrug off.

It might seem obvious that differences in each person’s immune system can affect how well they fight off pathogens. But uncovering the specific causes of this variation has enabled researchers to find ways to treat — and even prevent — severe infections that used to seem like random cases of bad luck, says Isabelle Meyts, an oncologist and immunologist who studies IEIs at the university KU Leuven in Belgium.

The discoveries have already begun to change clinical practice, for instance allowing doctors to genetically screen people for relevant mutations or supplement missing immune factors. And scientists are continuing to piece together the many ways in which genetic factors contribute to infectious diseases — especially in life-threatening cases. “What we’re realizing more and more is that there are probably inherited factors that predict who’s going to have severe reactions,” says Michael Abers, a physician-scientist studying infectious disease at Montefiore Einstein in New York City.

From germ to host

The germ theory of disease, popularized by Louis Pasteur in the nineteenth century, was revolutionary. The realization that microorganisms, invisible to the naked eye, could make people ill spurred public-health measures such as better hygiene, vaccines and anti-microbial drugs, which drastically improved outcomes for people with infectious diseases.

But even with these tools, there are still people — particularly some children and older people — who become sick and die from infections that are typically preventable or treatable, suggesting that there are limitations to focusing mostly on pathogens in the fight against infectious disease.

In the 1950s, some scientists were already drawing attention to the importance of the host, especially in cases in which ordinarily harmless microbes caused disease. Researchers have since discovered that one of the most important determinants of infection susceptibility might be a person’s genes.

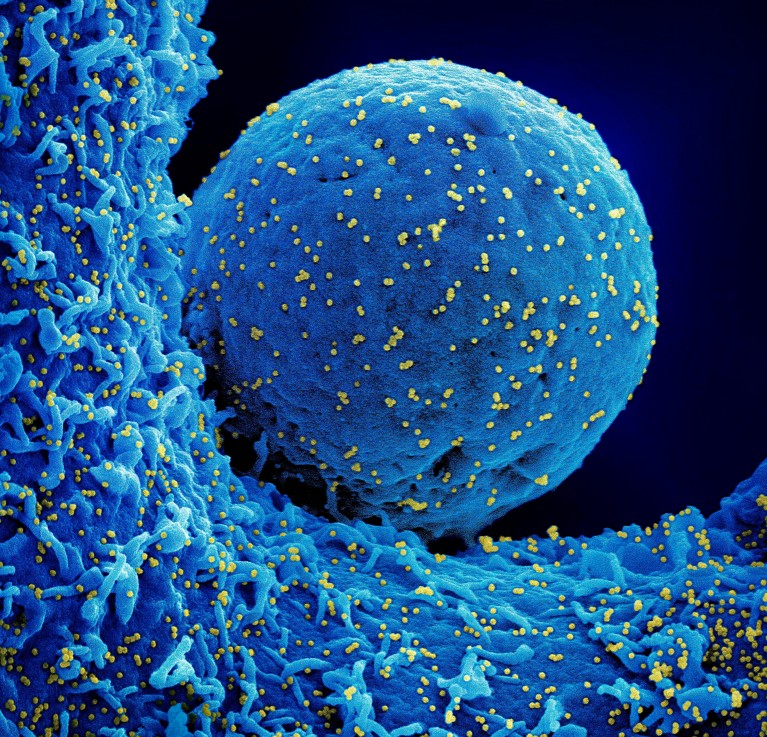

SARS-CoV-2 virus particles (yellow) infect a cell (blue).Credit: NIAID/NIH/SPL

Among the most famous demonstrations of genetic mutations driving infection outcome is severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), an inherited disease that leaves people without a functioning immune system and that is linked to mutations in more than a dozen genes. If left untreated, it typically leads to death before the age of two.

Fortunately, SCID is rare, occurring in an estimated 1 in 50,000 or so births. But inherited mutations that can cause problems in the immune system are much more common. Over the past few decades, researchers have found inborn errors of immunity linked to more than 500 genes3. In addition to infectious-disease susceptibility, these mutations are involved in other immune-system abnormalities, including autoimmune diseases and allergies.

Some mutations dampen the immune system and diminish its ability to fight off infections. But others can cause people to be hyper-responsive to infection, which can lead to runaway immune reactions that can turn deadly.

Although some IEIs can cause a generalized vulnerability to pathogens, most of them put people at risk from specific microbes, such as mycobacteria, avian influenza virus, herpes simplex virus and the bacterium Neisseria meningitidis.

“Each infection has a different set of mechanisms,” says Steven Holland, physician-scientist specializing in infectious disease at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland. “And unsurprisingly, there are different genes that speak to” different infections. The mutations known so far tend to cause severe disease, although some have been linked to recurrent milder infections.

On top of that, there are genes that can boost a person’s ability to fend off pathogens. For example, a mutation in the gene encoding CCR5, a receptor on the surface of white blood cells, makes people resistant to HIV4 (although it increases the risk of severe infection with West Nile virus). And mutations in the gene encoding FUT2, a protein located in the mucosa of the gut, helps people to fend off norovirus, a highly contagious gastrointestinal infection.

An expanding universe

In 2020, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was clear that some infected people became severely ill, whereas others got barely a sniffle. A massive consortium of scientists, led by paediatrician and immunologist Jean-Laurent Casanova at the Rockefeller University in New York City, discovered that around 10% of people with severe COVID-19 harboured autoantibodies — rogue proteins that turn against a person’s own body. These autoantibodies attacked signalling molecules that help to mobilize the immune response, tamping down the immune defences5.

Casanova and his colleagues have since found the same autoantibodies in a subset of people who develop severe disease from seasonal influenza, West Nile and many other diseases, as well as in those who experience rare adverse reactions to live vaccines, such as the yellow fever vaccine.

How your first brush with COVID warps your immunity

It’s not known exactly why and how autoantibodies develop. Some scientists, including Casanova, suspect that they might be the result of inherited or acquired mutations. He and others have identified some mutations that can give rise to these autoantibodies, such as deficiencies in various interferon-related genes. Whether such mutations can account for the majority of severe cases of these diseases remains to be seen.

Researchers are still working out the complex ways in which genetics contributes to infection outcome. Having a mutation doesn’t always make someone vulnerable: IEIs can behave unpredictably. Many people carry immunodeficiency-related mutations without ever experiencing their effects — a phenomenon known as ‘incomplete penetrance’. And although most IEIs with severe effects become apparent in childhood, some might lie dormant for decades. In unpublished work, Meyts and her team identified a person who has a mutation that is linked to inflammatory disease, but whose symptoms emerged only after a SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Scientists are still working to identify which factors influence the severity of IEIs. In a 2025 study, Dusan Bogunovic, a paediatric immunologist at Columbia University in New York City, and his colleagues discovered that, in about 4% of IEIs, the disease-causing variant can be expressed differently in different cells6. The team also found evidence that this process might be regulated by epigenetic mechanisms, which are influenced by environmental factors — suggesting that, not only might the same IEIs manifest differently in different people, but the effects of these mutations could change over a person’s lifetime. Bogunovic’s team is currently searching for the factors, such as inflammation or certain infections, that might control this variable allele expression.