Animal husbandry

The animal handling and experiments were performed according to protocols approved by the animal welfare officer at Institüt für Neurowissenschaften, Technische Universität München (TUM) and the relevant department at the regional government (Regierung von Oberbayern, Sachgebiet 55.2; animal protocol number 55-2-1-54-2532 10112 and 55.2-2532.Vet_02-24-5). Adult zebrafish (Danio rerio) were housed in the facility at the Institute for Neuronal Cell Biology at TUM. The adult fish were maintained in water temperature of 27.5–28.0 °C on the 14–10 h light–dark cycle. All experiments were performed on 6–9 days post-fertilization larvae of undetermined sex. The eggs were kept in 0.3× Danieau solution, and in the water from the fish facility upon hatching. The larvae were maintained at 28.0 °C and under the 14–10 h light–dark cycle.

Animal strains

All imaging experiments of the HD neurons were performed on fish carrying Tg(gad1b–Gal4)mpn155 (ref. 18) and Tg(UAS–GCaMP6s)mpn101 (ref. 46). To record the activity of habenula neurons (Extended Data Fig. 8), either Tg(vglut2a–Gal4)nns20 (ref. 26) (n = 6 fish) or a previously uncharacterized enhancer trap line Tg(18107–Gal4) was used (n = 2 fish) with UAS–GCaMP6s. The expression pattern of the 18107–Gal4 line can be browed on Z Brain Atlas (https://zebrafishexplorer.zib.de/home/). For labelling habenula for the ablation (Fig. 5 and Extended Data Fig. 9), Tg(18107–Gal4) was used. A subset of fish in the ablation experiment possessed Tg(UAS–nfsB–mCherry)47 for a logistical reason. This does not affect the results of the ablation experiments as they were evenly distributed across the conditions, and the fish were not treated with relevant chemogenetic reagents. The experiment to search for putative AHV cells (Extended Data Fig. 10e–j) was performed on fish carrying Tg(HuC–H2B–jGCaMP7c). All fish were mitfa−/− (that is, nacre) mutants lacking melanophores to allow optical access to the brain.

Two-photon microscopy experiments

Animal preparation and the stimulus presentation setup

Animals were embedded in 2% low-melting point agarose in 30-mm petri dishes. The agarose around the tail was carefully removed with a scalpel to allow tail movements. The dish was mounted on a 3D-printed pedestal and placed in a cube-shaped acrylic tank with the outer edge length of 51 mm. The height of the pedestal was designed so that the head of the animal came to the centre of the tank, taking the thickness of the dish and the typical amount of agarose into account. The tank was then filled with fish facility water to minimize the refraction due to the petri dish wall. The three sides of the tank (except for the one facing the back of the fish) were made of single-side frosted acrylic (PLEXIGLAS Satinice 0M033 SC), which functioned as projection screens. The diffusive side faced inwards to minimize the reflections between the walls. The visual stimuli were projected onto the three walls through two sets of mirrors with a previously described geometry16 (Supplementary Video 1), subtending 270° horizontally and 90° vertically. The larvae were lit with an infrared LED array through the transparent back wall of the tank. Their tail movements were monitored from below with a high-speed camera (Allied Vision Pike F032) at 200 Hz, through a hot mirror and a short pass filter to reject the excitation beam.

Microscope

Functional imaging was performed with a custom-built two-photon microscope. The excitation was provided by a femtosecond pulsed laser with 920-nm wavelength, the repetition rate of 80 MHz and the average source power of 1.8 W (Spark ALCOR 920-2). The average power at the sample was approximately 10 mW. The scan head consisted of a horizontally scanning 12-kHz resonant mirror and a vertically scanning galvo mirror, controlled by a FPGA running a custom LabView code (LabView 2015)48. Pixels were acquired at 20 MHz and averaged eightfold, resulting in the frame rate of 5 Hz. The typical dimension of the image was about 100 µm × 100 µm, with the resolution of about 0.2 µm per pixel. Only pixels corresponding to the middle 80% of the horizontal scanning range were acquired to avoid image distortion, and the area outside was not excited to minimize photo-damage. The fast power modulation was achieved with the acousto-optic modulator built in to the laser.

Stimulus protocols

All visual stimulus presentation and behavioural tracking were performed using Stytra package49 (v0.8). The panoramic virtual reality environments were created and rendered using OpenGL through a Python wrapper (ModernGL). In each frame of the stimuli, three views of the virtual environment corresponding to the three screen walls were rendered, which were arranged on the projector window to fit the screens. Behavioural tracking was performed as previously reported49. In brief, seven to nine linear segments were fit to the tail of the larva, and the ‘tail angle’ was calculated at each camera frame as the cumulative sum of the angular offsets between the neighbouring pairs of segments. To detect swimming bouts, a running standard deviation of the tail angle within a 50-ms window was calculated (‘vigour’). A swimming bout is defined as a contiguous period during which the vigour surpassed 0.1 rad. For each bout, the average tail angle within 70 ms after the onset was calculated, with a subtraction of the baseline angle 50 ms before the bout onset. This average angle (‘bout bias’) captures the first cycle of the tail oscillation in a bout and correlates well with the heading change in the freely swimming larvae50. We estimated the head direction of the fish in the virtual world as the cumulative sum of bout bias. The time trace of the head direction was also smoothed with a decaying exponential with the time constant of 50 ms, such that swim bouts result in smooth rotations of the scene (as opposed to instantaneous jumps).

For the recordings from the HD neurons, we simulated a virtual cylinder around the fish, whose height was determined so that the gaze angles to the top and bottom would be respectively ±60°. Various textures representing the visual scene, generated with the dimension of 720 × 240 pixel, were mapped onto this virtual cylinder. Dynamic aspects of the stimuli (that is, scene rotations and movements of the dots) were achieved by updating the textures on the cylinder. The visual scenes used were as follows:

-

Flash: uniform fields of black or white.

-

Sun-and-bars: three black vertical bars on a single radial gradient of luminance, ranging from white at the centre and black at the periphery. The bars were 15° wide and respectively centred at −90°, +75°,and +105° azimuths (0° is to the front and positive angles to the right). The centre of the gradient was in front and 45° above the horizon, and the radius was 135°.

-

Translating dots: dots randomly distributed in a virtual 3D space at the density of 7.2 cm−3 moved at 10 mm s−1 sideways. The dots within the 40-mm cubic region around the observer were projected as 3 × 3-pixel white squares against a black background (in a texture bitmap on the cylinder), regardless of the distance.

-

Stonehenge: four white vertical bars on a black background. The bars were positioned at −120°, −90°, 0° and +135° azimuths, respectively. The rightmost bar was broken in the vertical direction with the periodicity of 20° elevation and the duty cycle of 50%.

-

Cue-cards: a white rectangle with the 90° centred about the 0° azimuth, which spanned the elevation ranges of either above +20° (top cue) or below −20° (bottom cue). The background was black.

-

Noise: a 2D array of uniform random numbers within [0, 1], smoothed with a 5 × 5 pixel 2D boxcar kernel and binarized into black and white at 0.5.

-

Single sun: a radial gradient of luminance from white at the centre and black at the periphery, centred at −90° azimuth and 35° above the horizon, with the radius of 60°.

-

Double sun: the same as the single-sun scene, but symmetrized around the vertical meridian.

To identify and exclude naively visual neurons, each HD cell recording started with the alternating presentation of white and black flashes (8 s long each, five repetitions). In the experiment in Extended Data Fig. 3 the translating dots moving leftwards and rightwards alternatingly were also presented (8 s long, five repetitions). Afterwards, epochs of closed-loop scene presentations started. At the beginning of each epoch, the scene orientation was reset to 0°. On top of the closed-loop control, episodes of exogenous slow rotation (18° s−1) were superimposed intermittently (5 s every 30 s (Figs. 1 and 2 and Extended Data Figs. 3 and 4a–g) or 20 s (Figs. 3–5 and Extended Data Fig. 4h–m)). The directions of the rotations flipped after every four rotational episodes. The structures of the virtual cylinder experiments were as follows:

-

Sun-and-bars experiment (introduced in Fig. 1): in the first epoch (10 min), the sun-and-bars scene was presented. In the second epoch (10 min), fish received no visual stimuli (that is, darkness).

-

Translating dots experiment (introduced in Extended Data Fig. 3): in the first epoch (8 min), the sun-and-bars (n = 10 fish) or Stonehenge (n = 15 fish) scene was presented. In the second epoch (15 min), the fish observed translating dots moving either left or right. The dots disappeared and the screen turned uniform white if the fish performed a bout or 10 s passed without a bout (that is, no rotational visual feedback). The dots reappeared after waiting for 10 s.

-

Stonehenge experiment (introduced in Extended Data Fig. 4a–g): in the first and second epochs (8 min each), the sun-and-bars and the Stonehenge scenes were presented, respectively.

-

Cue-card experiment (introduced in Extended Data Fig. 4h–m): the sun-and-bars, bottom cue-card and top cue-card scenes were presented for 4 min each.

-

Jump and noise experiment (introduced in Fig. 2): in the first and second epochs (6 min each), the sun-and-bars scene was presented. In the second epoch, the superimposed exogenous rotations were swapped with abrupt 90° jumps. In the third epoch (6 min), the noise scene was presented.

-

Symmetry experiment (introduced in Fig. 3): in the first and third epochs (12 min each), the single-sun scene was presented. In the second epoch (12 min), either the double-sun scene (n = 25 fish; Fig. 3) or single-sun scene (n = 20 fish; Extended Data Fig. 7) was presented.

-

Ablation experiment (introduced in Fig. 5): in all epochs, the sun-and bars scene was presented. The first epochs were 12 min and 6 min long in the pre-ablation and post-ablation recordings, respectively. In the second epochs (6 min), the superimposed exogenous rotations were swapped with abrupt 90° jumps.

The experiment to characterize habenula visual responses (Extended Data Fig. 8) started with alternating black and white flash presentations (6 s each, five repetitions), which were used to select visually responsive cells. Next, white vertical or horizontal bars against a dark (25% luminance) background (which respectively subtended the entire height or circumference of the cylinder) were presented at 16 different azimuths and 5 different elevations, respectively. The width of the bar was 14°, and their azimuths and elevations were evenly spaced in the range of [−112.5° to 112.5°] and [−30° to 30°], respectively. Each presentation of bars lasted 4 s, with the interleave of 6 s. Each orientation and position combination were repeated three times, and the presentation order was randomized. Finally, the sun-and-bars scene rotating about the fish for the full 360° at 9° s−1 in an open loop was presented four times, in alternating directions. In the habenula ablation experiment, we recorded the responses of the habenula neurons to alternating black and white flash stimuli (8 s each, ten repetitions) to determine the visually responsive side (Extended Data Fig. 9b,c).

For the experiment to look for putative AHV cells (Extended Data Fig. 10e–j), we simulated a uniformly distributed point cloud in the 3D virtual reality environment (instead of simulating dots as a texture on the cylinder). Specifically, we simulated 2,000 dots within a cubic area with side length of 40 mm, and dots within the 20-mm radius from the observer were rendered as bright spots on a dark background with a diameter of about 1.2° (regardless of distance). Translational and rotational optic flow was simulated by moving the camera in the virtual environment. The experiment started with alternating presentations of short (5 s) yaw rotational optic flow and translational optic flow sideways, interleaved with 5 s of blank, dark screens, repeated five times, which were intended for characterizing the sensory responses of the cells. Next, leftwards and rightwards translational optic flow was continuously presented for 5 min each, which was intended to facilitate fish to turn, so that we could analyse the bout-triggered activity of the cells. The whole experiment was in open loop. The data acquired with two different sets of velocity parameters were merged together: in five fish, the speed of the rotational optic flow was 18° s−1, and the translational optic flow moved 90° to the side at 5.0 mm s−1. For the rest (n = 16 fish), the rotational optic flow was at 6° s−1, and the translational optic flow moved 45° to the side-front at 3.0 mm s−1.

Laser ablations

The habenula axons (that is, fasciculus retroflexus) were ablated unilaterally either by scanning a laser within a small region of interest (ROI) on the fasciculus retroflexus (setup A: Spectra Physics MaiTai, 830 nm, source power 1.5 W) or by pointing a laser on the fasciculus retroflexus (setup B: Spark ALCOR 920-2, 920 nm, source power 1.8 W). The pulsing characteristics of the two lasers were comparable (repetition rate of 80 MHz, pulse width of less than 100 fs), but ALCOR was group delay dispersion corrected and thus more efficient for ablations. On setup A, scanning with the duration of 200 ms was repeated 10 times with an interval of 300 ms. On setup B, a couple of approximately 100-ms-long pulses were delivered. These procedures were repeated until the successful ablation was confirmed either by a spot of increased fluorescence due to the photo-damage or a cavitation bubble. Ablations were repeated at two to three locations around the midbrain or pretectum levels to ensure the complete cut of the fasciculus retroflexus. The numbers of the fish treated on setups A and B were n = 8 and 8 (visual side ablated and control side, respectively) and 5 and 7 (visual side ablated and control side, respectively) fish, respectively. We waited at least 1 h after the ablation before making the post-ablation recordings.

Data analysis

Behavioural data analysis

The swim bouts estimated online during the experiments were analysed without additional preprocessing. In particular, we calculated trial-averaged cumulative turns around the exogenous scene rotations (Extended Data Fig. 1a,c,e–g), as well as comparing the biases of individual swim bouts with the scene orientation (Extended Data Fig. 1b,d).

Imaging data preprocessing

All imaging data were pre-processed using the suite2p package51. In brief, frames were iteratively aligned to reference frames randomly picked from the movie, using phase correlation. To detect ROIs representing cellular somata, a singular-value decomposition was performed on the aligned movie, and the ROIs were seeded from the peaks of the spatial singular-value vectors. All ROIs were used without morphological classifiers for cells, because the functional ROI selection procedure described below rejected spurious non-cell ROIs. In the ablation experiments, ROIs were manually defined, as described below.

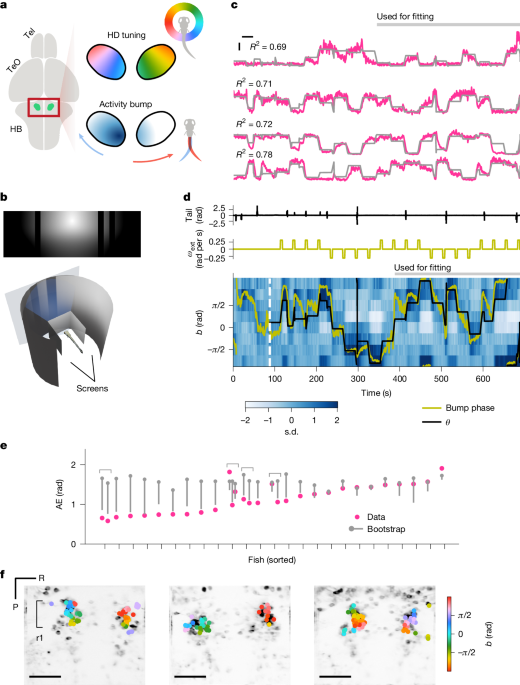

ROI selection

For the HD neuron recordings, fluorescent time traces were first normalized into Z-scores for each ROI by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation. The normalized traces were then smoothed with a box-car kernel with the width of 1 s. Next, a scaled shifted sinusoid \(a\times \cos (\theta -b)+c\) was fit to the smoothed traces of each ROI, where \(\theta \) is the orientation of the visual scene relative to the fish. The fitting was performed with the ‘curve_fit’ function from the scipy package, and parameters were bounded in the range of \(a\ge 0,b\in (\,-\,\pi ,\pi ]\). Only fractions of the data were used for this fitting to allow cross-validated quantifications of bump-to-scene alignments on the held-out fraction (described below). Specifically, either the second half of the first epoch (Figs. 1 and 3–5) or the entire first epoch (Fig. 2 and Extended Data Figs. 3 and 4) were used for fitting. ROIs with R2 larger than 0.15 were considered to be sufficiently modulated by the scene orientation and included. In addition, pairwise Pearson correlations of response time traces to repeatedly presented flashes (and translating dots in Extended Data Fig. 3) at the beginning of the experiments were calculated for each ROI, and averaged across all pairs of repetitions. Naively visual ROIs with mean pairwise correlations above 0.1 were excluded from further analyses. Finally, rectangular masks were manually drawn around rhombomere 1 of the aHB, and the ROIs outside the mask were excluded.

For the habenula recordings (Extended Data Figs. 8 and 9), ROIs with mean pairwise correlations in response to repeated flashes (as described above) higher than 0.3 were selected as visually responsive ROIs and used for further analyses. For the putative AHV cell experiment (Extended Data Fig. 10e–j), for each ROI, we first calculated the mean pairwise correlations over the repeated presentation of short optic flows (two rotational and two translational directions, with interleaves). We selected ROIs that had a mean above 0.4 as reliable sensory ROIs. Next, for each sensory ROI for each presentation of short rotational optic flow, we normalized the fluorescence time trace \(F(t)\) into \(\frac\Delta FF(t)=\fracF(t)-F_F_\), where \(F_\) is the average fluorescence within the immediately preceding 3-s period during which no stimulus was presented. We then averaged this \(\frac\Delta FF\) within the duration of each rotational optic flow presentation (that is, 5 s), and calculated the Z-scored directional difference

$$Z_\rmd\rmi\rmr=\frac{\mu _\rmC\rmW-\mu _\rmC\rmC\rmW}{\sqrt{\frac\sigma _\rmC\rmW+\sigma _\rmC\rmC\rmW5}},\,$$

where \(\mu _d\) and \(\sigma _d\) are the mean and standard deviation, respectively, of the time-averaged normalized response over five repetitions (\(d\in \\rmC\rmW,\rmC\rmC\rmW\\) (in which CW denotes clockwise and CCW denotes anticlockwise); which is plotted in Extended Data Fig. 10f). ROIs with \(|Z_\mathrmdir| > 2\) were further analysed as rotation-direction-selective ROIs.

Ablation experiment-specific preprocessing

For each fish in the ablation experiment (Fig. 5), we first analysed the responses of the habenula neurons to the repeated flash stimuli. We first identified visually responsive ROIs as described above, and defined the side with more visual ROIs as the ‘visual side’. In a minority of fish where the number of the visual ROIs from the two sides were close (within ±1 range), we determined the visual side based on morphology. This was possible due to the asymmetric expression of the 18107–Gal4. Overall, we found 3 fish with inverted laterality (that is, right visual) out of 28 included in the analysis (Extended Data Fig. 9c).

To compare the behaviours of the HD neurons before and after the fasciculus retroflexus ablations, ROIs were manually defined around the cells that were identifiable in both pre-ablation and post-ablation recordings. To minimize the effort for manual ROI drawing, we first used the ROIs detected by the suite2p pipeline from the pre-ablation recording, and run the HD cell selection procedure as described above. Using this as a guide, we drew manual ROIs on the pre-ablation recording, specifically focusing on the suite2p-based HD cell ROIs. We then calculated an affine transformation between the average frames of the pre-ablation and post-ablation recordings, and used this transform to register the manually defined ROIs to the post-ablation recordings. Finally, we manually adjusted the ROIs to better match the average post-ablation frames, if necessary. To make sure that we managed to identify the same cells across two recordings, we calculated the Pearson correlations of the smoothed fluorescence traces between all pairs of ROIs for each recording, and then computed the correlation of those correlations. We excluded fish with correlations of pairwise correlations below 0.4 from further analyses.

Characterization of HD tuning curves

To characterize the tuning of individual HD neurons, for each selected HD ROI, we calculated the average fluorescence binned according to the centred scene orientation \(\theta (t)-b\) (Fig. 4a–f and Extended Data Figs. 2b,c, 7g and 9i,j), where \(b\) is the preferred scene orientation of the ROI. To assess the width of these tuning curves, we calculated the fraction of \(\theta -b\) (that is, centred \(\theta \)) bins where the response was above half maximum (Extended Data Fig. 2b,c).

For the data in the learning epoch of the symmetry experiment, we refit the tuning curves with scaled-shifted sinusoid with the single or double frequency. That is:

$$a^\prime \times \cos (g(\theta -b)-b^\prime )+c^\prime ,$$

where g = 1 (single frequency) or g = 2 (double frequency), and \(b^\prime \) represents the tuning rotation in the learning epoch relative to the pre-learning epoch. Here we first compared the ROI-averaged R2 from the g = 1 fits and g = 2 fits (Fig. 4b) to check whether the tuning curves were single or double peaked. We then compared the difference in \(b\) and \(b^\prime \) for every pair of the HD cells in each recording, calculated the average of pairwise \(b^\prime \) difference binned by \(b\) difference and estimated the slope between the two (Fig. 4c–f).

For the ablation data, we refit scaled-shifted sinusoid (with single frequency) for each epoch of each recording and compared the changes of R2 before and after ablations, for each epoch type and each group (Extended Data Fig. 9i,j).

Bump phase calculation

As a readout of the population-level, instantaneous estimate of the scene orientation \(\theta (t)\) by the HD neurons, we calculated the bump phase \(\hat\theta (t)\), where \(t\) is discretized time. To do so, we first averaged the ROI-wise response time traces within eight 45° bins of the preferred orientation \(b\). We excluded fish with more than four empty bins from the following analyses. We then computed the bump phase as:

$$\hat\theta (t)=\mathrmatan2(y(t),\,x(t))$$

$$x(t)=\sum _ir_i(t)\cos b_i$$

$$y(t)=\sum _ir_i(t)\sin b_i,$$

where \(r_i(t)\) is the average response of the i-th bin at time t, and \(b_i\) is the central angle of the i-th bin. The bump amplitude was also calculated as \(A(t)=\sqrtx(t)^2+y(t)^2\).

Scene–bump alignments

The alignment between the bump phase \(\hat\theta \) and \(\theta \) were examined in several different ways. First, we calculated the centred scene–bump offset \(\Delta \theta (t)=[(\theta (t)-\hat\theta (t)+\pi )\mathrmmod2\pi ]-\pi \). For the cases where we can expect \(\Delta \theta \) to be 0, we simply averaged absolute \(\Delta \theta \) over time to obtain the ‘absolute error’ (AE) defined as \(\mathrmAE=\int |\Delta \theta |dt.\) Second, when we expected \(\Delta \theta \) to be non-zero but constant (that is, the bump follows the scene with an offset), we fit von Mises distribution \(\left(\frace^\kappa \cos (x-\mu )\int e^\kappa \cos xdx\right)\) to the histogram of \(\Delta \theta \), where \(\kappa \), a parameter that determines the peakiness of the distribution, can be interpreted as a proxy of how well the bump followed the scene. Third, in cases in which we expected the bump to follow the scene but with variable and non-unity gains (Fig. 2g), we calculated Pearson correlations between unwrapped \(\theta (t)\) and \(\hat\theta (t)\) within 15-s windows centred about the exogenous rotation episodes. We then calculated the median of these correlations over all rotation episodes, which we termed ‘local correlation’. To more explicitly estimate the gain of visual-based and motor-based angular path integration, for each of the above 15-s snippets of unwrapped \(\hat\theta (t)\), we performed a Ridge-regularized multiple regression by the exogenous component (that is, 90° rotation over 5 s) and the self-generated component (that is, the cumulative sum of bout biases) of \(\theta (t)\). The Ridge regression was performed using scikit-learn 1.1.2 with \(\alpha =1\), and the regression coefficients (that is, the gain of path integration) were constrained to be non-negative. These metrics were also compared with various nuisance variables (Extended Data Fig. 1h–j).

In the translating dots experiment (Extended Data Fig. 3), the change in bout phase was correlated with, as well as regressed by, the bias of swim bouts. For each bout in the translating dots epoch, the change in the bump phase \(\hat\theta \) was calculated as \(\hat\theta (\tau +5)-\hat\theta (\tau -1)\), where \(\tau \) is the bout onset (in seconds). For this calculation, we selected bouts that were separated by more than 5 s from both the preceding and the following bouts. A minority of bouts that had a bias of more than 120° and bouts in which tail tracking was faulty (tail not tracked in more than 10% of frames) were discarded as unreliable. Fish that did not have at least five such good bouts were excluded from the analysis. We had a single fish in the dataset that had two recordings that passed the above-quality thresholds. The correlations and slopes from multiple recordings in this fish were averaged.

Habenula visual responses

The visual receptive fields of habenula neurons were characterized as follows: first, for each ROI for each presentation of a bar, the fluorescence time trace \(F(t)\) was normalized into \(\frac\Delta FF(t)=\fracF(t)-F_F_\), where \(F_\) is the average fluorescence within the 2-s period immediately preceding the bar onset. The normalized responses were then averaged over repetitions for each orientation and position combination to generate the spatiotemporal receptive field maps as shown in Extended Data Fig. 8b, and averaged over time and divided by the peak response over positions to generate the normalized tuning curves in Extended Data Fig. 8c.

For the scene orientation decoding analysis, the responses of the visually responsive habenula ROIs were first concatenated across multiple recordings within each fish at different Z-depth. The response of each ROI was normalized into Z-scores for the entire recording (including the period during which the flashes and bars were presented; Extended Data Fig. 8d). Next, the normalized responses during the sun-and-bars scene presentation were downsampled to 1 Hz. For every pair of time points during the scene presentation \((t_1,t_2)\), we calcualted the Pearson correlation between the pattern of habenula activities, which we denote as \(r(t_1,t_2)\) (Extended Data Fig. 8e). For each time point during the scene presentation \(t\), the decoded scene orientation was defined as:

$$\widetilde\theta (t)=\theta (t_\max ),$$

$$t_\max =\rmargmax_\tau \r(t,\tau ).$$

For each fish, we calculated the absolute error \(\mathrmAE_\mathrmdecode\,=\)\(\int _40^160|\,\theta (t)-\widetilde\theta (t)\) to assess the quality of decoding.

Characterization of the putative AHV cells

To assess the anatomical distribution of the putative AHV cells, we mapped each recording into a common reference frame as follows: for each fish, alongside the planar functional recordings, we acquired a 1-µm or 2-µm step Z-stacks. First, we mapped the aligned, time-averaged frame of each functional recording onto the corresponding Z-stack with a manually defined key point-based affine transformation. Next, we mapped each Z-stack onto a single select Z-stack in the same way. This Z-stack-to-Z-stack mapping was performed separately for the groups of recordings targeted at rostral and caudal hindbrain regions. Then, we averaged the mapped Z-stacks across fish within the rostral and caudal groups. Finally, we mapped the average rostral stack onto the average caudal stack, exploiting the overlap between the two. The coordinates of all ROIs from all recordings in all fish were then linearly transformed into the average caudal stack coordinate with multistep affine transformations.

The bout-triggered activities of the rotation-direction-selective cells identified in the putative AHV cell experiment (Extended Data Fig. 10e–j) were characterized as follows: for each recording, we first identified turning swim bouts during the longer presentation of translational optic flows, which had the absolute bias above 0.2 rad. Recordings that did not have at least three turning bouts in both directions were excluded from further analyses. Next, for each ROI for each bout, we cut out a fluorescent snippet around the bout onset, and normalized it into \(\frac\Delta FF(t)=\fracF(t)-F_F_\), where \(F_\) is the average fluorescence within the immediately preceding 3-s period. The normalized bout-triggered snippet was averaged within 3 s from the bout onset and averaged across bouts for each direction. We then calculated the difference of time-averaged and bout-averaged bout-triggered activity by turn directions, as plotted in Extended Data Fig. 10g. To assess the contingency of visual and motor directional preferences, for each ROI, we calculated the product between the Z-scored rotational optic flow response differences (\(Z_\mathrmdir\)) and the directional differences of the bout-triggered responses (Extended Data Fig. 10h). This visuomotor product was averaged across cells within bins along the anteroposterior axis for each fish.

Statistical quantifications

As a rule, when comparing fish-wise metrics against null hypothesis values, or when making paired comparisons between different conditions within fish, we used the signed-rank tests. When comparing scalar metrics across two groups of fish, we used the rank-sum tests. To assess the significance of the alignment between the scene orientation \(\theta (t)\) and the bump phase \(\hat\theta (t)\) for each recording (more specifically, to show that the observed scene–bump alignment did not simply result from the autocorrelation of \(\theta \) and \(\hat\theta \)), we used bootstrap tests with time-domain shifting, as follows: first, we calculated a metric of interest that quantifies the scene–bump alignment as \(F_\mathrmdata=F(\theta (t),\hat\theta (t))\). We then circularly shifted the bump phase \(\hat\theta \) by a random amount \(\Delta t\) and recalculated the bootstrap metric \(F_\mathrmBS=F(\theta (t),\hat\theta ([t+\Delta t]\mathrmmodT))\) for 1,000 times, where T is the duration of the relevant epoch or the experiment. We then calculated the probability of obtaining a value more extreme than \(F_\mathrmdata\) in the expected direction from the resampled distribution \(F_\mathrmBS\) as the estimate of the statistical significance (that is, bootstrap P value) of the observation. Thus, the bootstrap tests were one-sided. When \(F(\theta ,\hat\theta )\) depended on the temporal structure of \(\theta \) and \(\hat\theta \) (that is, local correlation and regression), care was taken such that the data snippets containing discontinuous points introduced by the circular shifting were not used for the \(F_\mathrmBS\) calculation. To make sure that the observed significant fish-wise P values did not simply result by chance in the absence of true bump–scene alignments (that is, multiple comparison problem), we performed Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests to compare the observed P value distribution with a uniform distribution.

The specific statistical tests we performed, as well as the experiment specific exclusion criteria, are as follows:

-

Sun-and-bars experiment: the absolute error \(\mathrmAE=\int |\Delta \theta |dt\) was calculated for the hold-out (that is, not used for the HD cell identification) portion of the data, and its significance was tested with the bootstrap test (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Fig. 2e).

-

Translating dots experiment: the correlation between the bout phase change across swim bouts and the bias of the swim bouts was tested against 0 with a signed-rank test (Extended Data Fig. 3f).

-

Stonehenge experiment: von Mises distributions were fit on the histogram of \(\Delta \theta \) (with 16 evenly spaced bins) in the Stonehenge epoch, and \(\kappa \) was tested with the bootstrap test (Extended Data Fig. 4d,g).

-

Cue-card experiment: von Mises distributions were fit on the histogram of \(\Delta \theta \) in the bottom and top cue epochs, and \(\kappa \) was tested with the bootstrap test (Extended Data Fig. 4k,m). In addition, \(\kappa \) was compared across epochs within each recording with a signed-rank test (Extended Data Fig. 4l).

-

Jump and noise experiment: von Mises distributions were fit on the histogram of \(\Delta \theta \) in the jump and noise epochs, and \(\kappa \) was tested with the bootstrap test (Fig. 2f and Extended Data Fig. 5b,c). In addition, local correlation (Fig. 2h and Extended Data Fig. 5b,c), as well as trial-averaged R2 from the multiple regression model (Fig. 2f and Extended Data Fig. 5e–g) were calculated on the noise epoch data and tested with the bootstrap test.

-

Symmetry experiment: several fish whose bump amplitude \(A\) decayed more than 60% between the pre-training and post-training epoch (for example, owing to poor health) were discarded as unreliable. The ‘fraction out-phase’, that is, the proportion of time where \(|\Delta \theta | > \frac3\pi 4\) was calculated for each epoch (only using the hold-out part) and compared across epochs with signed-rank tests, separately for the double-sun (Fig. 3e) and control (Extended Data Fig. 7d) groups. The change in the fraction out-phase from the pre-learning to the post-learning epoch was compared across groups with a rank-sum test (Extended Data Fig. 7e). In Fig. 4b, ROI-averaged R2 from single-frequency and double-frequency sinusoidal fits on the individual HD cell tuning curves in the learning epoch were tested against each other with a signed-rank test. In Fig. 4f, the slope between the pairwise tuning difference and the tuning rotation difference was tested against 0 with a signed-rank test. In Fig. 4i, von Mises distributions were fit on the histogram of \(2\theta -\hat\theta \), and \(\kappa \) was tested with the bootstrap test (Extended Data Fig. 7h).

-

Habenula experiment: the absolute error of decoding was tested against \(\frac\pi 2\) with a signed rank test (Extended Data Fig. 8f).

-

Ablation experiment: von Mises distributions were fit on the histogram of \(\Delta \theta \) for each epoch in each recording. We then compared the \(\kappa \) across the ablation group within each epoch of each recording with signed-rank tests (Fig. 5e). In addition, the ratios of \(\kappa \) between pre-ablation and post-ablation recordings for each epoch were compared across the ablation groups, using the rank-sum test (Fig. 5f). We excluded fish that had \(\kappa < 0.5\) in the pre-ablation epochs, as they were not informative about the effect of the ablations. In addition, visuomotor multiple regression models were fit to the bump-phase changes in the smooth epoch of the post-ablation recordings in the visual-side-ablated animals, and R2 was tested with the bootstrap test (Extended Data Fig. 10c,d). We also tested the amount of stabilization turns fish made before and after ablations for each epoch–group combination, with signed rank tests (Extended Data Fig. 1g).

-

Putative AHV cell experiment: the binned-averaged visuomotor product was tested against 0 for each anteroposterior bin, with signed-rank tests (Extended Data Fig. 10i).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.