Device preparation and electrical measurements

The procedure for device fabrication from PdGa crystal using Ga-ion-based focused-ion beam technique is as follows32. A lamella was milled out of the bulk crystal. Then the lamella was transferred in situ to the TEM grid for polishing till the desired thickness is achieved. The thickness of the lamella used to make devices in our study ranges from 1 μm to 4 μm. Then the lamella was microstructured into desired three-arm geometry on the TEM grid. Then the microstructured lamella was transferred in situ onto the SiO2 substrate with prepatterned Au contact pads. The electrical contacts between the lamella and the contact pads were made by sputtering Ti–Au bilayers. Then the etching step was carried out to remove shorting between the electrical contacts. During the device preparation procedure, special care was taken to reduce the surface damage. For example, the transport channel in the device was never scanned with the Ga ion beam after the fine polishing step. However, surface damage of few tens of nanometres may still exists even after several fine polishing steps. Therefore, a dry etching step using low-energy Ar ion was performed to further reduce the thickness of this amorphous layer before the deposition of Ti–Au to make electrical contacts. The effect of surface damage on transport measurements was also studied by purposefully damaging the sample surface with the ion beam. The comparison of results before and after ion-irradiation were compared to study the influence of the amorphous layer on transport. As also observed in previous studies, the increase of the amorphous layer thickness did not negatively influence the transport response through topological states33.

The electrical measurements were primarily performed in a Bluefors LD−400 dilution refrigerator. Meanwhile, experimental data in Fig. 4 with the applied magnetic field of 2 T were measured in a PPMS DynaCool cryostat. The electrical measurements were carried out using Zurich Instruments lock-in amplifiers (MFLI) at 7.919 Hz and 13.333 Hz reference frequencies. The oscillator voltage amplitude was varied to sweep the applied current through the device (with a buffer resistance in series). The higher harmonic voltage responses from devices were simultaneously measured with the multi-demodulator option provided in an MFLI. Each demodulator produces two output signals: one corresponding to the in-phase component (X) and the other to the quadrature component (Y) relative to the reference signal. Special considerations were taken to increase the signal-to-noise ratio, such as using high-frequency electronic filters and avoiding ground loops. The magnetic field orientation was swept using a three-axis superconducting magnet from American Magnetics in a Bluefors refrigerator (Fig. 4b(ii)). An out-of-plane rotator puck was used in the PPMS case, in which the rotation axis is along the applied current under the magnetic field of 2 T (Fig. 4b(i),c). Two different configurations of electrode contacts with the electrical transport channel in a device were studied. It was observed that the measured third-order voltage responses were more prominent when the Ti–Au connected the top surface of the channel with the electrical contacts. The enhanced third-order response made it possible to measure the Bθ dependence of the third-order response, as shown in Fig. 4b(ii),c(ii).

We have measured 23 devices fabricated in different geometries and crystal orientations. The five focal crystal orientations are presented in Extended Data Table 1. We can define four working states of the valve, depending on the relative magnitude of the chiral currents in the two arms. We have quantified the position of the valve using the term \(\phi =\tan ^-1\frac\bfV_3\omega ^\rmR\bfV_3\omega ^\Gamma \), as shown in Extended Data Fig. 1. ϕ = 45° represents ‘valve on’ state, when there are equal magnitudes of the NLH currents from the Γ and R Fermi pockets in the right and left arms, respectively. ϕ = 0° represents ‘IΓ on’ state and ϕ =90° represents ‘IR on’ state, where NLH current in the right arm is predominantly generated due the Γ Fermi pocket and that in the left arm is predominantly generated due the R Fermi pocket. Finally, the ‘valve off’ state, in which chiral current generation is suppressed in both arms. We made four devices in a three-arm geometry near to the ‘valve on’ position. All four devices show the same experimental features discussed in the paper, namely, the appearance of distinct NLH responses of similar magnitude in different arms after the current threshold and their distinct symmetries of first-order responses with magnetic field orientations, as discussed in Fig. 3b(i),c(i). The absolute value of the nonlinear response varied with the dimensions of the device, as given in the Extended Data Table 2. The modulations of the third-order responses discussed with Fig. 3b(ii),c(ii) were observed in two of these devices. A good signal-to-noise ratio is needed to measure the nonlinear responses in the presence of the magnetic field, which we posit is a limiting factor in our PPMS system. We made three Mach–Zehnder interferometer (MZI) devices with a ‘valve on’ crystallographic position. All three showed oscillations in third-order response with applied current and magnetic field, as discussed in Fig. 5. The interference visibility ϑ for the MZI with ϕ = 49.4° and 38.6° were 0.86 ± 0.06 and 0.69 ± 0.1, respectively. ϑ was calculated using the relation \(\fracV_3\omega ^\mathrmamp-V_3\omega ^\mathrmavgV_3\omega ^\mathrmamp+V_3\omega ^\mathrmavg\), where \(V_3\omega ^\mathrmamp\) is the distance between the peak and crest of the oscillation, which is calculated using \(|V_3\omega ^\max -V_3\omega ^\min |\) and \(V_3\omega ^\mathrmavg\) is the mean offset of the oscillation given by \(|\fracV_3\omega ^\max +V_3\omega ^\min 2|\). \(V_3\omega ^\max \) and \(V_3\omega ^\min \) are the minimum and maximum values of the V3ω signal. We also found that ϑ was sensitive to the electronic properties of the conduction channel sidewall. The value of ϑ increased when the sidewall opposite to the voltage probe is not electrostatically screened by a presence of another electrode.

Passive and active control of the chiral fermionic valve

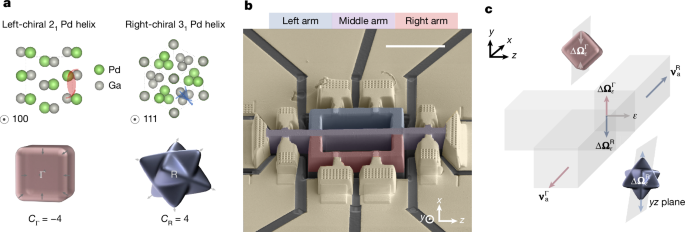

The chiral currents generated in the two arms of the device depend on the magnitudes of \(\Delta \boldsymbol\Omega _\varepsilon ^\Gamma \) and \(\Delta \boldsymbol\Omega _\varepsilon ^\rmR\), as given in equation (1). We can control the relative projection of \(\Delta \boldsymbol\Omega _\varepsilon ^\Gamma \) and \(\Delta \boldsymbol\Omega _\varepsilon ^\rmR\) along y, using the distinct symmetry of the Fermi pockets at the Γ and R points. Although the symmetry of a crystal is defined by its space group, the symmetry of a Fermi pocket is determined by the local symmetry of the band structure at a given k-point47. Therefore, Fermi pockets at the Γ and R points can locally exhibit distinct mirror-like symmetry \(\mathcalM^* \), which maps \((k_x,k_y,k_z)\,\longrightarrow \,(k_x,-k_y,k_z)\) (refs. 38,47). The projection of the net OAM along the y-axis is zero if a \(\mathcalM^* \) exists along the xz-plane. \(\mathcalM^* \) can selectively exist for only one of the Fermi pockets at Γ or R depending on the crystallographic direction of applied current. For example, when the current passes along [100] (z-axis) and the NLH-induced chiral current is collected along [010] (x-axis), \(\mathcalM^* \) exists along the xz-plane for the Fermi pocket at Γ, whereas it is broken for the Fermi pocket at R. Thus, the OAM contribution from topological bands at R would predominantly exist along the y-axis. Extended Data Fig. 2a(i),(ii) shows the third-order and second-order responses in each arm in a device fabricated in the mentioned crystallographic directions. We can observe that the chiral current is primarily generated in the left arm of the device. It represents the valve in the ‘IR on’ state because the chiral current in the left arm preferentially exists in the Fermi pocket at R. The opposite is true when current is passed along the [100] (z-axis) and chiral current is collected along the [011] (x-axis). In this case, the OAM contribution from the topological bands at Γ would predominantly exist. Extended Data Fig. 2b(i),(ii) shows the nonlinear responses measured in a device made along these crystal directions. In this case, nonlinear currents are predominantly generated in the right arm of the device, thus representing the valve in the ‘IΓ on’ position. Finally, Extended Data Fig. 2c(i),(ii) shows the nonlinear responses in a device in the ‘valve off’ states where the generation of chiral current is suppressed in both arms. In this case, the current is passed along [011] and NLH currents were collected along [100]. We call this strategy to control the valve position ‘passive’ because the valve tunability is linked with the intrinsic quantum geometry of the topological bands rather than the experimentally controlled parameter.

We now discuss a proof-of-concept study to achieve active tunability of the valve. As discussed in the main text, the chiral fermionic current exists due to the preferential occupation of the R Fermi pocket in the left arm and Γ Fermi pocket in the right arm of the device. Thus, the magnitude of chiral currents can be controlled by tuning the occupational imbalance between two Fermi pockets. We fabricated a magnetic tunnel junction (MTJ) with in-plane magnetization on top of individual arms to locally probe the influence of the magnetic field on chiral currents. We developed a new fabrication technique to ensure the surface of the lamella is at a similar height to the substrate. Our strategy prevents any sudden height changes to ensure smooth deposition of the MTJ. Extended Data Fig. 3a shows the false-coloured SEM image of the prepared device with MTJ electrodes deposited on top of the left and right arms. The lamella was prepared in the ‘valve on’ position. In the first set of experiments, we studied the effects of the magnetization direction of the MTJ on the chiral current of both arms. Mx and Mz represent directions when the magnetization of MTJ is perpendicular and parallel to the current-induced orbital magnetization. Extended Data Fig. 3b(i),(ii) show the V3ω responses at 77.77 Hz in the left and right arms, respectively, with Mx and Mz magnetizations. We can observe from Extended Data Fig. 3b that the chiral current has the same order of magnitude in the left and right arms for the Mx orientation. However, the nonlinear response of the right arm switches sign when the MTJ magnetization was switched from Mx to Mz; meanwhile, the V3ω response in the left arm remains similar. Notably, these measurements were performed in the absence of an external magnetic field. The magnetic field was only used to switch the magnetization direction of the MTJ. Extended Data Fig. 3b shows a possible strategy to tune the valve state from ‘valve on’ to ‘IR on’, based on a MTJ magnetization switching mechanism. In the second experiment, we varied the frequency of the applied current to study the interaction of the chiral current with the magnetization of MTJ by measuring the inductive impedance. Extended Data Fig. 3c shows the dependence of V3ω responses at different frequencies of the applied current with the MTJ in the Mx configuration. We note from Extended Data Fig. 3b(ii),c(ii) that the impedance response of IΓ is not significantly changed when the frequency is varied between 77.77 Hz and 47 Hz, whereas the impedance response of IR is reduced by half. From Extended Data Fig. 3c(i), we see that the magnitude of IR is further reduced by an order of magnitude upon going to the frequency of 23 Hz. Meanwhile, the IΓ response, although diminished, has the same sign and the order of magnitude. Through Extended Data Fig. 3c, we show that the valve can be tuned from ‘valve on’ position to ‘IΓ on’ position by changing the frequency of the applied current from 77.77 Hz to 23 Hz with the MTJ in the Mx configuration. Through these two experiments, we provide a first step to pursue active tunability of the chiral fermionic valve by its integration with an MTJ. However, a deeper understanding of the interaction between the chiral current and the magnetization dynamics is needed to further analyse these results. Also, a systematic study is crucial to analyse the switching reproducibility, fidelity and scalability of the MTJ-integrated device, which presents an important direction for future work.

Quantum Interference below threshold current

We have shown the appearance of the V3ω responses after a certain current threshold in Fig. 2. Meanwhile, Fig. 5b shows clear oscillations of V3ω with applied current even below the threshold current. As shown in Extended Data Fig. 4a, we could also observe weak V3ω oscillation response below the threshold current in the three-arm geometry as well. The subsequent question is that why does the interference occur even below the threshold current. We can explain the observed phenomenon using the schematic shown in Extended Data Fig. 4b. We discussed in the main text that the fermions in different Fermi pockets gain a transverse velocity due to the presence of \(\Delta \boldsymbol\Omega _\varepsilon ^\Gamma ,\rmR\). Equation (1) shows the magnitude of the current going into different arms of the device from different Fermi pockets is proportional to \(\Delta \boldsymbol\Omega _\varepsilon ^\Gamma ,\rmR\). The appearance of a nonlinear response after the current threshold suggests that \(\Delta \boldsymbol\Omega _\varepsilon ^\Gamma ,\rmR\) is non-zero only above it. However, \(\boldsymbol\Omega _\varepsilon ^\Gamma ,\rmR\) does exist on individual topological Fermi pockets even when \(\Delta \boldsymbol\Omega _\varepsilon ^\Gamma ,\rmR\) is zero. The presence of \(\boldsymbol\Omega _\varepsilon ^\Gamma ,\rmR\) causes the fermions to contribute to the scattering equally in both arms of the device from both of the Fermi pockets. Therefore, the chiral current in each of the arms would not be preferentially carried by one of the Fermi pockets. However, the chiral currents in both of the arms do exist. But, the nonlinear responses of current with opposite chirality cancel out below the threshold current. \(\Delta \boldsymbol\Omega _\varepsilon ^\Gamma ,\rmR\) becomes non-zero above the threshold current. Thereby, the fermions from the Fermi pockets at Γ and R, are preferentially scattered into the right and left arms, respectively. This creates an occupational imbalance in these arms, which leads to the observation of the chiral current response from the individual Fermi pockets. The presence of chiral current in both scenarios makes it possible to observe the quantum interference of the chiral current even below the threshold current.

Theoretical considerations for the NLH effect

We use the semi-classical Boltzmann formalism to derive the nonlinear responses. However, it is crucial first to discuss the limitations of the assumptions taken to derive these transport equations. The semi-classical Boltzmann approach considers electrons as an adiabatic Bloch wavepacket moving in a static band structure. We have shown with Figs. 2 and 3 that the nonlinear transport responses appear only above a certain current threshold. Therefore, the conventional Boltzmann approach cannot capture the electric field-induced transitions due to the non-equilibrium bands associated metric. Second, the formalism assumes a single distribution function per band, effectively treating all carriers as coming from a single Fermi surface. However, we have shown chirality-selective transport due to the imbalance in the occupation of two different Fermi pockets with opposite Chern numbers. These currents of different chirality may have different scattering and relaxation dynamics, which must be incorporated in the transport equations. Moreover, the assumption of a localized and non-interacting Bloch wavepacket used in the Boltzmann formalism cannot be used to accurately describe the phase-coherent transport of multifold fermions. Nevertheless, we have found that the Boltzmann formalism is very useful to qualitatively describe our experimental results.

The current density Jx flowing into the outer arms of the device along x, as shown in the schematic of Fig. 1c, is given by

$$\bfJ_x=-\rme\int _\bfkfD\bfv_x$$

(2)

with \(\int _\bfkx\equiv \int \frac\rmd^3\bfk(2\rm\pi )^3\) and f is the non-equilibrium distribution function, vx is the velocity of an electron wavepacket along x and D is the modified density of states, given as

$$D=1+\frace\hbar \bfB\cdot \boldsymbol\Omega $$

(3)

In the case of B = 0, the motion of electron wavepacket is given by the equation

$$\bfv_x=\frac1\hbar \frac\partial \epsilon (k)\partial \bfk+\frace\hbar \boldsymbol\mathcalE\times \boldsymbol\Omega $$

(4)

where \(\epsilon (k)\) is the energy dispersion relation. The first term is the group velocity, whereas the second term is the anomalous velocity. As described in the main text, we purposefully applied \(\boldsymbol\mathcalE_z\) along the principal axes of PdGa to minimize the Ohmic contribution of \(\boldsymbol\mathcalE_z\) along x. Thus, the group velocity along x due to \(\boldsymbol\mathcalE_z\) would be close to zero. Thus incorporating \(\bfv_x\) in equation (2) gives

$$\bfJ_x=-\frace^2\hbar \int _\bfkf(\boldsymbol\mathcalE_z\boldsymbol\Omega _y)$$

(5)

In the relaxation time approximation, the non-equilibrium distribution function with a first-order correction is given by

$$f=f^+f^(1)=f^+\frace\tau \boldsymbol\mathcalE_z1-i\omega \tau \frac\partial f^\partial \bfk$$

(6)

where \(f^\) is the Fermi–Dirac equation, \(\tau \) is the intranode scattering and \(\omega \) is the frequency of the applied a.c. electrical signal \(\boldsymbol\mathcalE_z\)(= E0sin(ωt)). On substituting equation (6) in equation (5), the current density Jx can be written as the sum of first-order and second-order electric-field terms \(\bfJ_x^(1)\) and \(\bfJ_x^(2)\) as

$$\bfJ_x^(1)=-\frace^2\hbar \int _\bfkf^\boldsymbol\Omega _y\boldsymbol\mathcalE_z$$

(7)

$$\bfJ_x^(2)=-\frac\tau e^3\hbar (1-\rmi\omega \tau )\int _\bfk\frac\partial f^\partial \bfk\boldsymbol\Omega _y\boldsymbol\mathcalE_z^2\,\propto \,\int _\bfkf^(\partial _\bfk\boldsymbol\Omega _y)\boldsymbol\mathcalE_z^2$$

(8)

In equation (7), the overall integration of \(\boldsymbol\Omega _y\) throughout the Brillouin zone under TRS should be zero. However, \(\bfJ_x^(1)\) may contribute to first-order transverse current in our device geometry as shown in Fig. 1c under non-equilibrium steady-state conditions. However, there would be equal contribution from both of the Fermi pockets without any preferential scattering. The voltage response of \(\bfJ_x^(1)\) would be in-phase with the applied current, represented as \(V_\omega ^X\) in Extended Data Fig. 5(i). Meanwhile, \(\bfJ_x^(2)\) originating due to OAM dipole37 would be of second-order, since \(E_^2\sin ^2(\omega t)=E_^2(1-\cos (2\omega t))/2\). Its voltage response would be \(\rm\pi /2\) shifted with respect to the applied current, represented as \(V_2\omega ^Y\) in Extended Data Fig. 5(ii). Extended Data Fig. 5a,b shows the experimental measurement of these responses for the left and right arms of the device.

In our experiments, the above equations correspond to our observed voltage responses below 55 μA, where the g is zero and the Berry curvature is the dominant quantum geometry component. As discussed in the main text, the quantum metric is non-zero above 55 μA and we get a field-induced Berry curvature \(\boldsymbol\Omega _\varepsilon ,y=\nabla _k\times (\bfG\boldsymbol\mathcalE_z)\). Substituting this into \(\bfJ_x^(1)\) and \(\bfJ_x^(2)\) converts them into second-order and third-order transverse currents, respectively, which are given by

$$\bfJ_x^(2)\propto \int _\bfkf^(\nabla _\bfk\times (\bfG\boldsymbol\mathcalE_z))\boldsymbol\mathcalE_z$$

(9)

$$\bfJ_x^(3)\propto \int _\bfkf^\partial _\bfk(\nabla _\bfk\times (\bfG\boldsymbol\mathcalE_z))\boldsymbol\mathcalE_z^2$$

(10)

These equations are the basis of the experimental data discussed in the main text in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3. \(\bfJ_x^(3)\) will contribute to a first-order and third-order current response, because \(E_^3\sin ^3\omega t\,=\) \(E_^3\left(\frac34\sin \omega t+\frac14\sin (3\omega t+\rm\pi )\right)\). Their voltage response would be in-phase with the applied current applied current, represented as \(V_\omega ^X\) and \(V_3\omega ^X\) in Extended Data Fig. 5.

We also observed \(\rm\pi /2\) shifted responses of \(V_\omega ^X\), \(V_2\omega ^Y\) and \(V_3\omega ^X\). These responses are shown in Extended Data Fig. 6, Fig. 3 and Fig. 2(i), respectively. The appearance of \(V_\omega ^Y\), \(V_2\omega ^X\) and \(V_3\omega ^Y\) due to \(\bfJ_x^(1)\), \(\bfJ_x^(2)\) and \(\bfJ_x^(3)\), respectively suggests the presence of an inductive impedance, as suggested by Faraday’s law. These responses only start to dominate after the current threshold of 55 μA is reached when g is non-zero. It suggests that the inductance experienced by the chiral fermionic current in the right and left arms is the function of gΓ and gR, respectively. The dependence of \(V_\omega ^Y\), \(V_2\omega ^X\) and \(V_3\omega ^Y\) responses on \(\bfg\) allowed us to capture its opposite sign for topological Fermi pockets at Γ and R points. Notably, it also suggests that the chiral fermionic current carries orbital angular moments. As in our case, it will lead to generation of a spin current since PdGa has a large spin–orbit coupling3. The inductance values for the chiral currents following into the right and left arm can convey the magnitude of these currents. We used the overall applied current applied in the device in our calculation, which gives the lower limit estimation of the inductance reactance, as given in Extended Data Fig. 6.

Theoretical considerations for the quantum interference of chiral current

The phase acquired by a free electron due to electric-field-induced Berry connection (Aε) in the absence of an external magnetic field along the path j is given by

$$\theta =\frace\hbar \int \bfA_\varepsilon \cdot \rmd\bfl_j$$

(11)

In our system the vector potential Aε experienced by an electron in the left and right arms is GR\(\boldsymbol\mathcalE_z\) and GΓ\(\boldsymbol\mathcalE_z\), respectively. Thus, the phase difference due to the acquired by the electron travelling along the left (\(\theta _\rmR\)) and right (\(\theta _\Gamma \)) arms is given by

$$\Delta \theta =\theta _\rmR-\theta _\Gamma =\frace\hbar (\int \bfG^\rmR\mathcalE_z\cdot \rmd\bfl_j-\int \bfG^\Gamma \mathcalE_z\cdot \rmd\bfl_j)$$

(12)

Assuming \(\bfG\) does not vary spatially, we can rewrite the above equation as

$$\Delta \theta =\frac\rme\hbar (\bfG^\rmR-\bfG^\Gamma )\Delta V_z$$

(13)

where \(\Delta V_z\) is the voltage difference across the MZI. The term \(\bfG^\rmR-\bfG^\Gamma \) is non-zero as G of Fermi pockets at R and Γ have opposite signs. Thus, we would observe the oscillation in phase on applied current, as shown in Fig. 5b.

Temperature dependence

Extended Data Fig. 7a-c show the log-scaled temperature dependence of the first-order, V3ω and V2ω longitudinal responses in one of the arms of the device. Extended Data Fig. 7a shows that the first-order response decreases with temperature till 15 K after which it starts to saturate. Upon cooling further, the V3ω and V2ω responses start to appear, as shown in Extended Data Fig. 7b,c. The appearance of the V3ω response is concurrent with the observed upturn in the first-order response, as expected from equation (1). The V3ω and V2ω responses start to appear below 3.4 K and 14 K, respectively. The exact transition temperature varied between devices, with different device geometries and crystallographic orientations. However, the concurrent appearance in the upturn of the first and third-order responses was always observed in all the measured devices. Data at lower temperatures were measured in a Bluefors system which showed that the nonlinear responses start to saturate below 1 K. Note that these data are not shown because they had a considerably better signal-to-noise ratio due to the low-noise filters present in the Bluefors system. Extended Data Fig. 7d,e shows the relative modulation of the first-order responses with magnetic field orientation in the right and left arms, respectively, at different temperatures. The modulation in the different arms remains of opposite signs below 100 K even in the device with ‘valve off’ position. After 100 K, the change in the sign of the modulation in the right arm was observed. Thereafter, both arms share the same sign of modulation, albeit of different magnitudes. Above 200 K, the modulation with magnetic field orientation starts to disappear in both of these arms.

Extended Data Fig. 7f shows the temperature dependence of the FFT amplitude of the V3ω oscillation with the magnetic field. The amplitude of the oscillation decays slowly with temperature below 1 K, after which it starts to decreases more sharply with temperature. The amplitude decay trend matches the temperature dependence of the magnitude of the V2ω shown in Extended Data Fig. 7c. We strongly believe that the FFT amplitude is linked with the quantum metric magnitude. The V2ω response is the direct indicator of quantum metric response. Assuming amplitude decay solely due to an inelastic mechanism would not be accurate as the quantum metric does not scale with the scattering time in Drude conductivity. Therefore, the amplitude decay was not correlated to the phase-coherent length because the mechanism of decoherence of chiral fermions is not completely known. We also tried to measure the amplitude of the oscillation of the V3ω response with applied current shown in Fig. 5b. We observed that the oscillation period changed with temperature, and the FFT amplitude broadened into multiple peaks. Hence, tracking the FFT amplitude with temperature was not trivial. It may be due to temperature variation of current-induced magnetization, which influences the oscillation period.

Possible trivial-state contributions to current directionality

PdGa belongs to a gyrotropic class with the tetrahedral chiral point group 23 (T), which allows for a Dresselhaus-type spin–orbit coupling48. The spin–orbit coupling can cause splitting of the trivial band (and topological bands). The applied electric field creates non-equilibrium spin polarization of both spins, as shown in Extended Data Fig. 8a. The current applied along z would create a spin polarization for both spins along z. A previous study in 2002 proposed the spin galvanic effect, in which electric current was produced due to spatially uniform non-equilibrium spin polarization49. Empirically, the electric current density (jα) is linked with the average spin of the electron (\(S_\gamma \)) by \(j_\alpha =\sum Q_\alpha \gamma S_\gamma \), where Q is the second-rank pseudotensor of a gyrotropic crystal. These currents are semi-classically modelled using spin-dependent scattering asymmetry. In the conventional spin galvanic effect, the current is galvanized because of the asymmetry in spin-flip scattering, which requires a spin population imbalance of a particular spin. However, opposite spin currents can also be galvanized because of the asymmetry in skew scattering, as in the case of inverse spin Hall effect, as schematically shown in Extended Data Fig. 8b. Similar to the spin galvanic effect, the inverse spin Hall effect also generates a dipolar term proportional to (k · S) because of spin-dependent correction of the Fermi–Dirac distribution (\(\delta f_k,S\)) (ref. 50). For non-zero \(Q_xz\), this would generate currents of opposite spins in different arms of the device, instead of the spin Hall voltage measured in a conventional Hall device. The spin currents generated due to inverse spin Hall effect (or spin galvanic effect) can give the desired current directionally solely due to the trivial bands of PdGa. This filtration of spin current into different arms is conceptually similar to the filtration of the chiral fermions due to electric field-induced quantum geometry.

The magnitude of opposite spin currents galvanized into the outer arms would depend on the size of the Fermi surface51 and \(\delta f_k,S\). These parameters are similar for both spin currents originating from the Fermi surface of a same trivial band. Therefore, we would expect that the relative magnitude of current in both arms would remain similar. It would be irrespective of the crystallographic direction of applied current, even when the magnitude of individual spin current may vary because of anisotropic skew scattering. In Extended Data Fig. 2, we have shown that we can tune the relative magnitude of the generated current in both arms by passing current in different crystal directions. Therefore, the spin currents galvanized due to \(Q_\alpha \gamma \) of trivial bands cannot explain the differences in the relative magnitude of currents measured in different devices. We will now provide the second evidence by ruling out the involvement of the \(Q_\alpha \gamma \)-like tensor from the trivial bands. We measured anomalous Hall response in three devices with crystallographic orientation corresponding to ‘valve on’, ‘IR on’ and ‘IΓ on’ positions. Extended Data Fig. 8c shows the electrical configuration used to measure the Hall responses. The magnetic field was rotated in the yz plane, where θ = 90° corresponds to the field along the direction of applied current z. Extended Data Fig. 8d shows the relative change in the magnitude of the Hall response on magnetic orientation in a device with ‘valve on’ position with respect to θ = 90°. The response in this valve position resembles the response expected from a trivial Hall effect. \(\Delta \boldsymbol\Omega _\varepsilon ^\Gamma \) and \(\Delta \boldsymbol\Omega _\varepsilon ^\rmR\) have a similar magnitude contribution to the OAM dipole in the ‘valve on’ position. Therefore, there is no anomalous Hall response due to the absence of any net magnetization. The Hall response was also similar in the device in ‘valve off’ state, which is expected because of the absence of the OAM dipole itself along the y-axis. Extended Data Fig. 8e,f show the relative change in the magnitude of the Hall response with the magnetic field orientation in the device in ‘IR on’ and ‘IΓ on’ position, respectively. These responses show the presence of an anomalous Hall response with distinct symmetries. In ‘IR on’ position, a net magnetization is present because \(\Delta \boldsymbol\Omega _\varepsilon ^\rmR\) has larger contribution in the OAM dipole than \(\Delta \boldsymbol\Omega _\varepsilon ^\Gamma \). The symmetry of the Hall responses matches the symmetry of the longitudinal response of chiral current discussed in Fig. 4b(i). Meanwhile, \(\Delta \boldsymbol\Omega _\varepsilon ^\Gamma \) contributes more to the OAM dipole in ‘IΓ on’ position; therefore, the anomalous Hall response captures its two-fold symmetry. The three distinct anomalous Hall responses observed in our study cannot be explained by \(Q_\alpha \gamma \)-driven currents. Our results indicate that the observed two distinct Hall responses can be explained only by considering the \(\Delta \boldsymbol\Omega _\varepsilon ^\Gamma \) and \(\Delta \boldsymbol\Omega _\varepsilon ^\rmR\) contributions coming from two different topological Fermi pockets.

Role of Fermi-arcs in long-range coherence

The phase coherence of electrons in a typical metal such as Cu is typically of the order of few tens of nanometre. However, we show in our device that the phase coherence length of chiral current is above 15 μm. The long coherence length is due to the chiral nature of the charge carriers in the topological states. There are three possibilities of electronic states for fermions to occupy when they scatter into the left or right arm of the device due to va. They can scatter into (1) trivial states; (2) topological states with opposite chirality; or (3) topological states with the same chirality. The chiral fermions scattering into trivial states would violate the Nielsen–Ninomiya theorem23. It would imply fermions losing their chirality on scattering into non-chiral trivial states. Thus, the decoherence of chiral current into trivial states cannot occur even in the presence of empty trivial states near the Fermi-level. The fermions can also undergo inter-valley scattering into the topological states with opposite Chern number. Notably, Fermi-arc states existing on the surface provide a direct pathway for the fermions to switch their chirality as it connects the topological band crossings with opposite Chern numbers. We present our hypothesis of the role of Fermi-arcs in preserving the phase coherence of chiral fermionic currents. There are two pairs of spin-split Fermi-arcs that connect the Γ point to the R points at the corners of the Brillion zone at the top and bottom surfaces3. The chiral current \(I_\omega ^\rmR\) can leak into the Γ band by the Femi-arcs present on the surface, whereas the opposite will occur for the chiral current \(I_\omega ^\Gamma \). Thus, the flow of the leakage current is outward from Γ to R in the right arm, whereas it is inwards towards Γ from R in the left arm. We posit that the presence of current-induced magnetization of opposite polarities prevents the charge relaxation through Fermi-arcs in both arms. Consequently, the chiral current due to the preferential occupancy of topological bands can have longer relaxation times.