Universities have three core missions: research, teaching and societal impact. The third is increasingly defined in commercial terms. The number of intellectual property licences has increased and more spin-out companies are being formed. This shift is supported by an independent review of spin-out practices1, standardized investment guidance2 and the professionalization of university technology-transfer offices3.

The future of universities

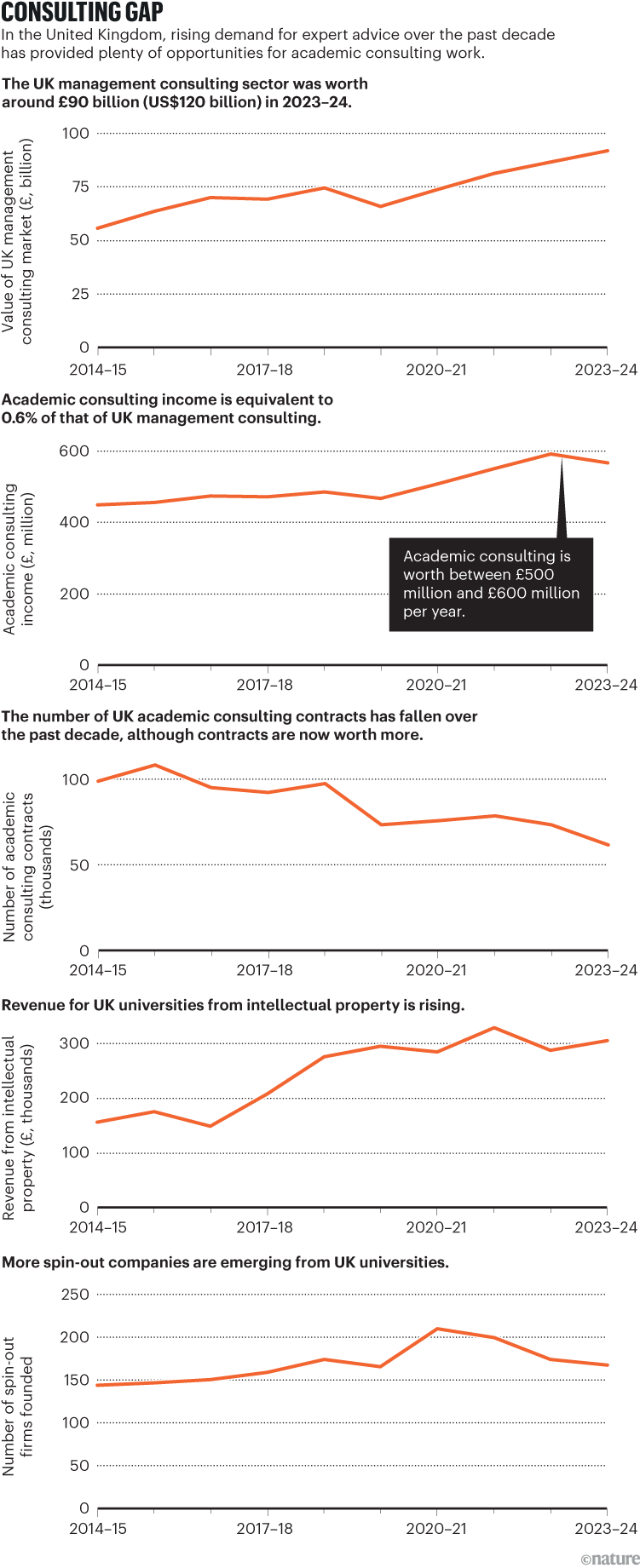

By contrast, academic consulting work, one of the most direct and scalable means by which academics can shape industry, government and civil society, remains underdeveloped (see ‘Consulting gap’).

Consulting work and other routes for exchanging knowledge are often treated as administrative functions. Such activities are defined and measured inconsistently and receive limited recognition in evaluations of research-related innovation. At a time when universities are struggling financially and academic research is often seen as distant from people’s everyday concerns, that must change.

Here, we call for universities to make it easier for academics to carry out consulting work. If the work is properly supported, it can diversify income, build enduring partnerships and ensure that research delivers a tangible impact.

Why consulting work matters

There are widespread benefits to academics offering their advice to outside organizations for a fee. For higher-education institutions, consulting work can provide a flexible stream of income at a time of financial strain. It can foster partnerships with industry and government that generate collaborative research, joint ventures and fresh sources of funding.

It reinforces universities’ reputation as engines of applied knowledge and economic and societal impact. For example, one small software team at the University of Southampton, UK, turned open-source verification tools into more than £600,000 (US$799,000) of consulting income by advising on safety-critical railway systems between 2014 and 2021 (see go.nature.com/44ueoch).

For academics, consulting also offers professional development, wider networks, financial reward and real-world experience. It creates career porosity between academia, industry and policy, opening routes into leadership roles. For example, consulting can underpin the spin-out-company model: an academic who created intellectual property might be engaged as a ‘fractional executive’ through a consulting contract, allowing them to contribute to the company and develop leadership skills. Consulting work also enriches the research culture of higher-education institutions, giving academics direct feedback on how their work is used in practice, informing grant proposals and strengthening career progression.

Sources: Value of consulting market, Office for National Statistics; Academic consulting, IP and spin-out data, Higher Education Statistics Agency

For society, consulting accelerates the application of knowledge to national priorities, such as clean energy, health and social policy. It provides a mechanism for organizations to benefit from publicly funded research. It also ensures university expertise is applied beyond the campus walls, and can feed back into teaching with real-world case studies that better prepare graduates for the workforce.

Higher-education institutions could embed modules that simulate the practice of consulting engagements to enhance students’ understanding of work. In one example, industry-led consulting projects were developed at Henley Business School, UK, to give master’s students hands-on experience.

Consulting, therefore, is one of the most immediate channels through which universities can deliver societal impact. These projects are typically shorter in duration and easier to set up than other routes to impact, such as spin-out companies. Yet, across most institutions, consulting receives limited attention.

Lost opportunity

Using data from the UK Higher Education Statistics Agency on the number of consultancy contracts and academic staff at nine universities, we found that less than 10% of academic staff, on average, engaged in consulting work. Academic consulting is worth roughly £500–600 million per year (£566 million in 2023–24). That’s equivalent to 0.6% of the UK management consulting market value (£92 billion according to the Office for National Statistics), or 2.8% of the sector, based on the definition of the London-based Management Consultancies Association (£20.4 billion).

Over the past decade, the number of academic consulting contracts has fallen by 38% from around 99,000 in 2014–15 to fewer than 62,000 in 2023–24. Higher average values of contracts have driven some growth, with the linear trend in total academic consultancy income rising by 31% from 2014–15 to 2023–24. But that falls short of the trend in the UK management consulting sector, which was 51% over that period.

Some institutions have demonstrated what is possible. In 2023–24, 17 UK universities earned more than £10 million annually from consulting work across a vast range of disciplines and industries, including drug-development advice, advanced materials testing, digital health evaluation, engineering analysis, and policy and socio-economic consulting.

Medical parasitology consultant Wellington Oyibo reports on anti-malaria strategies.Credit: Adekunle Ajayi/NurPhoto via Getty

Data are less available for institutions in other countries; limited information (including personal communications with US technology-transfer offices) suggests that consulting income typically does not make up a large share of institutional turnover. This suggests a global underutilization of academic expertise through consulting, even among the world’s most research-intensive universities — and a lost revenue stream for higher education. Management consulting alone in the United States was valued at $407 billion in 2025, according to market research firm IBIS World.

Private consultancy firms are increasingly moving into this underexploited market, capturing opportunities that universities neglect. Small-scale (under £5,000), fast-turnaround, one-off projects are commonly sidelined by university contract offices because they represent too small an income for strained institutional resources, creating space for contract-research organizations and technical consultancies with the agility to capture this demand. If universities do not act, global professional services firms will continue to dominate the space in which academic insight could deliver direct societal benefit.

Policy patchwork

Weak institutional policies on consulting are one reason for this missed opportunity. We examined policies at 30 universities hosting at least 5 UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) Future Leaders Fellows — a 7-year fellowship programme designed to develop research and innovation leaders in academia and business — supplemented by surveys of 76 fellows and interviews with technology-transfer staff at the same universities. Our analysis reflects practices across a subset of research-intensive institutions, including our own, and is intended to inform sector-wide discussion rather than prescribe a single model.

Great science happens in great teams — research assessments must try to capture that

The results reveal a fragmented system. Two-thirds of the universities we surveyed have publicly available policies, two of which prohibit private consulting. Permitted university-contracted time for consulting ranges from unlimited to 30 days or fewer per year, or to personal time only. Institutional charges range from 10–40% of consulting fees.

When we conducted interviews with staff who manage academic consulting services across multiple UK universities, administrative delays and inconsistent incentives or recognition of consulting were often cited as common issues. The result is a patchwork of practice, in which opportunities depend less on expertise and more on institutional flexibility.

The financial outcomes for academics vary widely, from flexible fees agreed between client and academic to university-set day rates. Some academics choose to put their consulting income into research accounts at their institution to support their group or department, but whether this is permitted, and on what terms, varies between universities and even across departments in the same institution. At some organizations, up to 50% of an individual’s earnings can be diverted into institutional research funds.

Services to support academic consulting also differ between universities and within them, with some departments or technology-transfer offices providing insurance, contracting and negotiation support, and other institutions providing none. Contract approvals range from a 24-hour turnaround to months of negotiations. Faced with these obstacles, some academics turn to private consulting conducted outside their employment contracts, often without legal cover and sometimes in breach of institutional terms.