Our visitor from deepest space is now departing from whence it came. Last Friday, the interstellar comet designated 3I/ATLAS completed its closest approach to Earth without crashing into us or depositing an invading armada. In fact, “closest” here means 168 million miles, or a little under twice the distance from Earth to the Sun. Whew! Dodged that one. From here, our friend from beyond the stars will continue on its lonely quest through our solar system. Per Space.com, 3I/ATLAS will visit Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune over the next few years, finally leaving us all behind somewhere in 2028. Whatever you’re looking for out there, I hope you find it, buddy.

While our friend may not actually be an alien spacecraft — sorry everyone — it sure has blown everyone’s mind. It could be as old as the Milky Way galaxy itself. As the Sun has melted the icy comet, it has discharged cyanide (which is normal for comets, somehow), CO2 in unusual quantities, and even bizarre elements like the metals nickel and iron. It’s also only the third interstellar object ever detected in our solar system (hence the “3I” in the name), making it a scientific goldmine. This mysterious outsider wasn’t in town for long, but this town may never quite be the same.

The flight of 3I/ATLAS

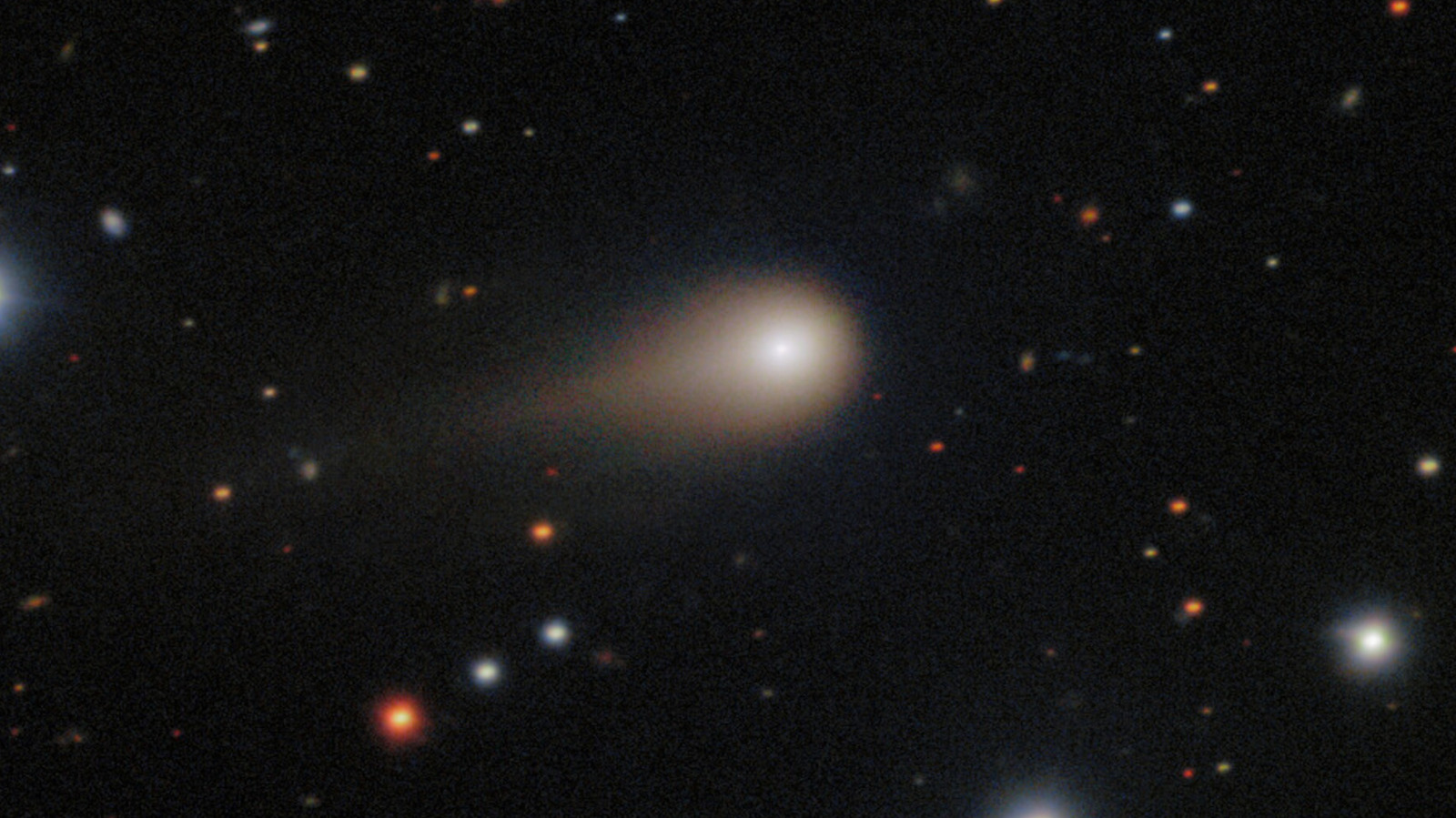

The other part of its name comes from the system of telescopes that first detected it, the Asteroid Terrestrial-Impact Last Alert System (ATLAS). This picture from the European Space Agency shows our respective flightpaths; note that Earth orbited away from the comet after ATLAS’ scope in Chile first spotted it in early July. Since then, it has passed very close to Mars before going behind the Sun (relative to Earth). As of Friday, even though 3I/ATLAS has its eyes on the galactic horizon, the Earth has orbited around the Sun enough to come as near as it ever will to the already departing visitor. Fare thee well.

Good thing ATLAS did its job there! It’s designed to spot anything that might crash into us, and it successfully saw this near-miss coming. It sure would be bad if, say, ever-increasing satellite constellations started obscuring all observatories to the point of rendering them nearly useless. If that actually happens, then we might not even know the next interstellar visitors are even here. And if one of them does want to, shall we say, make an impact, our first idea of it might be on touchdown.