In spring, consumers in the United States found themselves having to hunt for something that had previously been exceedingly easy to find: eggs. Some supermarkets limited customers to a single carton per visit, but still ran out. Shoppers who did manage to find eggs in stock paid dearly — a dozen could sell for more than US$11. For many people, it was the first indication that the country was in the midst of a devastating bird-flu outbreak.

The H5N1 flu virus responsible for this outbreak hit poultry farms especially hard. The egg shortage and skyrocketing prices were the result of the loss of tens of millions of hens — the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) requires the destruction of poultry flocks that test positive for H5N1. Egg prices have now fallen. But US consumers could experience another shock if they buy a turkey for their Thanksgiving meal in late November. This year’s flock is the smallest in decades, partly due to bird flu. Some economists predict that turkey prices will be 40% higher this year than in 2024.

Nature Spotlight: Influenza

Some poultry farms contracted H5N1 from waterfowl. But others got the virus from a new source of infection. In March 2024, the United States announced that several herds of dairy cattle had been infected. Since H5N1 jumped to cattle, the virus has infected at least 1,000 cows in 18 states, tens of millions of chickens and turkeys, and 70 people, one of whom died.

H5N1’s move into dairy cattle, which come into close contact with humans, has infectious-disease specialists on alert. “This was not on our potential-pandemic bingo card,” says Thomas Friedrich, a virologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The virus hasn’t developed the capacity to easily transmit between humans, but that doesn’t mean that it never will, he adds. And “we’re not doing enough to take the threat as seriously as I think we should”.

In April 2024, the federal government began requiring dairy farmers to test cattle for H5N1 before moving them between states. And late last year, it launched a milk-testing programme. But it’s not enough, says Carol Cardona, an avian-influenza researcher at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. “We want to see a comprehensive national plan that addresses all susceptible species,” she says. Dairy cows are among the latest species to contract H5N1, but they won’t be the last.

The current clade of H5N1 circulating the globe has been detected in dozens of animal species, including cats, seals and mice. Specialists worry that the more the virus circulates in mammals, the greater the chance it will acquire the mutations it needs to transmit between humans, sparking a global pandemic. “If we don’t take and maintain steps to actively detect infection of cattle and then, when it’s detected, to stop the spread of virus from farm to farm, then the danger persists,” Friedrich says.

First contact

When Kay Russo, a veterinarian at RSM Consulting in Fort Collins, Colorado, heard about a mystery illness circulating in dairy cattle in Texas, she worried that it might be avian influenza.

The United States has introduced a milk-testing programme to monitor the H5N1 virus.Credit: Michael M. Santiago/Getty

Russo started her career as a dairy veterinarian, but after returning to university to specialize in poultry medicine, she has been following the spread of the H5N1 strain from wild birds to a host of different species. Speaking to vets in Texas, she asked how the wild birds on the farms were behaving, and one vet replied that they were all dead. “This is going to sound nuts,” she remembers saying, “but it sounds like it could be flu.”

Evidence suggests that the virus circulating in cows came from a wild bird in December 20231. On many commercial poultry farms, birds stay indoors where they are protected from wildlife. Cows and wild birds, however, mix freely — in the pasture, at the water trough and when they eat.

Many researchers initially thought this ‘spillover’ event was a freak occurrence, says Friedrich. “There was something unique about this particular constellation of genes that we call B3.13 that enabled the virus to jump from birds to cattle.”

Since then, however, a virus with a different genotype, called D1.1, has also jumped from wild birds to cattle on at least two occasions, in two different locations. Scientists still don’t know how or why this is happening, but it does suggest that the interface between dairy cattle and wild birds needs more attention.

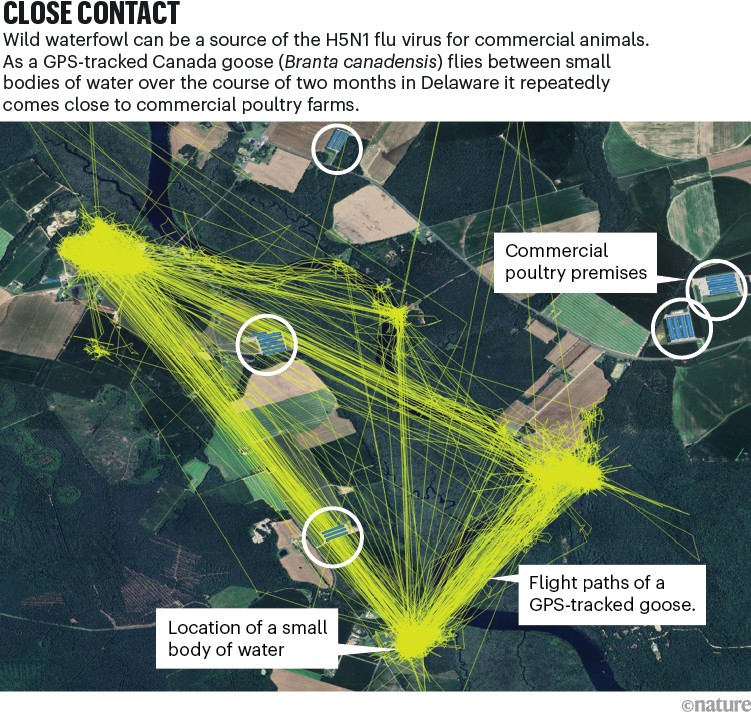

Cows can’t be raised in enclosures like poultry can, but there are other ways to minimize contact with wild birds. The biggest problem, says Maurice Pitesky, an epidemiologist who studies poultry health at the University of California Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, is the built environment. “In some cases, farms are located near prime waterfowl habitat,” he says. In others, wild birds have to rely on suboptimal habitats, such as poultry and livestock lagoons (see ‘Close contact’).

Source: Maurice Pitesky

Reinventing the construction of dairy farms isn’t feasible, but keeping waterfowl away from them by making habitat less attractive is, Pitesky says. That might mean using nets over ponds to prevent birds from landing, or employing lasers and sound cannons to scare birds away. “You want to reduce the potential for spillover,” he says.

Cow conundrum

Once a spillover occurs, the focus shifts to curbing the spread of the virus — both from animal to animal and from farm to farm.

Among poultry, H5N1 is deadly. So poultry operations tend to have good biosecurity measures in place. If a bird tests positive for H5N1, all the poultry on that farm are culled.

Snuffing out H5N1 in dairy herds is trickier, partly because the disease is milder. Cows infected with H5N1 might produce less milk or stop eating, but rarely do the animals die. The H5N1 control strategy for cattle has focused on identifying and isolating sick animals. “The hope initially was that this would burn out in cattle and we wouldn’t have to worry about it,” says Russo, who calls that “the stick-your-head-in-the-sand approach”.

Some countries vaccinate chicks against the H5N1 virus. Credit: Fang Dehua/VCG via Getty

The USDA recommends that producers implement biosecurity measures on dairy farms to prevent the spread of H5N1. For example, it suggests that farms disinfect the tyres of vehicles when they arrive, treat infected milk before disposal and ensure that farm workers use personal protective equipment. But those measures cost time and money, and many dairy producers don’t have a strong incentive to implement them. “The only way that they are going to take up improved biosecurity is if cows start dying,” says Keith Poulsen, director of the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Researchers still don’t understand how the virus moves from farm to farm. Theories include the virus being transferred by birds, insects or farm workers; brought in by vehicles; or even carried on the wind. Cows’ udders could be the point of entry, or it could be respiratory. “We’re not sure what the riskiest pathways actually are,” says Michelle Kromm, a turkey veterinarian and an expert in food-system risk management, who works as a consultant in Minneapolis, Minnesota. This lack of clarity makes it difficult to formulate the best plan of action.

In a preprint in August2, researchers showed that the virus seems to be widespread on dairy farms in California. The team found infectious virus in milk, in wastewater manure lagoons, and even in the air — both in milking parlours and on cows’ breath.

That suggests there could be a couple of simple risk-mitigation strategies, says Seema Lakdawala, a virologist at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, who co-led the research. In milking parlours, “we’ve got lots of aerosols, lots of infectious virus”, she says. Face masks could prevent infections in workers, and fans could help to reduce the amount of virus carried in the air. Lakdawala also points out the importance of disinfecting milking equipment and inactivating virus in the milk of infected cows before it is discarded, so that it doesn’t enter the waste stream. “There is no one mode of transmission for influenza viruses,” she says. “One intervention is not going to solve everything.”

The management of dairy herds also makes control difficult. Poultry producers operate what they call an ‘all in, all out’ strategy, meaning the entire population of animals on a given farm cycles in and out together. But on a dairy farm, Russo says, about one-third of the animals are replaced every year. That means there is a constant supply of cows with no immunity to the virus. And stopping the movement of new cows is nearly impossible. In many cases, dairy production is broken up geographically. One farm might raise the calves, another takes the animals once they’re ready for breeding, and a third deals with the lactating cattle. Dairy farmers can’t just turn the switch off and stop production, Poulsen says.

As a result of these obstacles, little has been done to curb the virus’ spread. “The way that a dairy clears virus is living through the infection as it moves through the herd,” said California’s state veterinarian Annette Jones when she testified before the US House Subcommittee on Livestock, Dairy, and Poultry in July. “Some of our herds have been under quarantine for over 300 days. So that means they are potentially spreading virus in the environment that long.”

Infected dairy farms can be devastating for poultry producers. A single infected cow sheds enough virus to “wipe out an entire poultry operation”, Russo says. “Twenty-eight million out of the 39 million egg-layers we lost last year were associated with dairy cattle spillover events.”

This kind of spillover is exactly what happened in May at Hickman’s Family Farms in Buckeye, Arizona. The virus spread from a nearby dairy to one of the egg producer’s cage-free farms. The company had to cull six million birds — 95% of its flock. “It’s just been a slow-motion train wreck,” president Glenn Hickman said on a podcast in July.