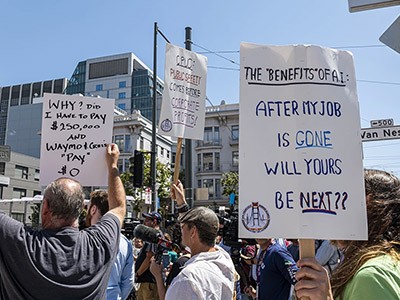

How will artificial intelligence reshape the global economy? Some economists predict only a small boost — around a 0.9% increase in gross domestic product over the next ten years1. Others foresee a revolution that might add between US$17 trillion and $26 trillion to annual global economic output and automate up to half of today’s jobs by 20452. But even before the full impacts materialize, beliefs about our AI future affect the economy today — steering young people’s career choices, guiding government policy and driving vast investment flows into semiconductors and other components of data centres.

Why evaluating the impact of AI needs to start now

Given the high stakes, many researchers and policymakers are increasingly attempting to precisely quantify the causal impact of AI through natural experiments and randomized controlled trials. In such studies, one group gains access to an AI tool while another continues under normal conditions; other factors are held fixed. Researchers can then analyse outcomes such as productivity, satisfaction and learning.

Yet, when applied to AI, this type of evidence faces two challenges. First, by the time they are published, causal estimates of AI’s effects can be outdated. For instance, one study found that call-centre workers handled queries 15% faster when using 2020 AI tools3. Another showed that software developers with access to coding assistants in 2022–23 completed 26% more tasks than did those without such tools4. But AI capabilities are advancing at an astounding pace. For example, since ChatGPT’s release in 2022, AI tools can now correctly handle three times as many simulated customer-support chats on their own as they could before5. The better, cheaper AI of tomorrow will produce different economic effects.

Second, carefully controlled studies do not capture the wider ripple effects that accompany AI adoption. For example, the studies involving call-centre workers3 and software developers4 found that when organizational structure remained fixed, the less-experienced workers benefited most from AI assistance. But in the real world, managers might respond by reorganizing work or even replacing some of the less-experienced workers with AI systems. If they do, the effect on those individuals could be the opposite of that estimated in controlled studies. Indeed, payroll data suggest that employment of younger workers has declined since 2022, particularly in occupations that include tasks that AI excels at, such as customer service and software development6. However, researchers are still trying to understand how much of the pattern is attributable to AI technology.

Carefully controlled studies are like flashing a bright, narrow spotlight: they are only part of the illumination needed to understand how society is adapting to AI. With so much still unknown about its broader economic and social effects, popular debate often slips into speculative, science-fiction narratives of a world dominated by machine intelligence.

Social science could help to navigate these uncertainties, but it would require both imagination and grounding. Here, I describe three complementary approaches that can guide researchers working in this rapidly evolving field.

Social science fiction

One approach is to create what economist Jean Tirole calls social science fiction7 — speculation about the future that remains rooted in fundamental economic principles and behavioural theories. Rather than relying on imagination alone, this kind of analysis uses models to explore how technologies might interact with market forces.

For example, in 2019, researchers modelled how self-driving cars might reshape cities and found that the vehicles could make traffic worse8. Because passengers in self-driving cars can relax, read or watch videos, the personal cost of time spent in traffic falls. But as more people choose to travel by car, they impose greater congestion on others. Whether that leads to inefficiency will depend on whether governments implement policies such as congestion pricing to correct the ‘externality’.

Can AI help beat poverty? Researchers test ways to aid the poorest people

Another illustration of imaginative, yet grounded, social science comes from research on how market forces might limit AI’s disruptive potential. Studies9,10 suggest that, as automation boosts productivity in some tasks, other activities that cannot easily be automated — such as creative direction or vetting final outputs — will grow in relative value. That might raise demand for labour, and therefore wages, in such jobs. These opportunities could cushion some of the disruptive effects of automation. But it might also deepen inequalities between people who thrive in these roles and those who do not.

More thought experiments like these can help policymakers to imagine how the economy might shift in a more disciplined manner. Such experiments can identify which indicators to monitor and provide a head start on planning the policies that might be needed. Other open problems include understanding the incentives to create knowledge for AI systems, and how innovation and economic growth might be affected if AI labs remain competitive with each other, or if one pulls ahead as a clear market leader.

Forward-looking data

As well as theory, policymakers will also need evidence to understand how the economy will change. Different types of information need to combine to form a more complete picture.

One common approach to assessing AI capabilities is benchmarking — testing the systems on standardized tasks, much as exams do. Benchmarks can assess an AI system’s ability to solve mathematics problems, respond to customer-support requests or diagnose medical conditions. However, benchmark scores often diverge from performance in real-world settings, where tasks are noisier, more complex and context-dependent. For example, a medical AI system might perform well on textbook-style clinical questions, but could misinterpret communications from patients if they omit key details. More research is needed to design benchmarks that better capture real-world performance.

If AI is anywhere near as transformative as many expect, its effects will show up in numerous indicators that can be monitored in real time, such as tracking which tasks people use AI for. These usage data show, for instance, that AI chatbots are often used for software development, suggesting that this sector might feel the earliest effects of AI adoption11,12. Other indicators include employment, job openings and whether firms that integrate AI earn higher profits and expand. However, there will be questions that such descriptive indicators alone cannot answer. For that reason, researchers might still attempt to measure the causal impact of AI: that is, whether AI causes improvements, rather than merely being adopted by high performers who also happen to be more willing to try new technologies.

AI can supercharge inequality — unless the public learns to control it

Estimating AI’s causal effects is difficult because the technology is evolving and organizations are adapting. But this challenge is not unique to AI. Similar issues arise when evaluating how any pilot programme — whether in business, education or public health — will perform once it is expanded. When scaled up, programmes often encounter fresh constraints or trigger wider economic fallouts. Economists have developed methods to anticipate these scaling effects when designing experiments, such as replicating the conditions of the eventual implementer — for example, a government agency — rather than those of the more agile, well-resourced organizations that typically run pilots13–15. Researchers studying AI can similarly attempt to anticipate future changes when designing experiments.

One important parameter is the cost of running AI models, which has been falling. Researchers can model how cost declines might affect the viability of different applications. For example, one study16 examined AI usage by teachers in Sierra Leone who pay for Internet access by the megabyte. In early 2022, querying an AI chatbot was 12 times more expensive than loading a standard web page; by 2025, thanks to falling compute costs and the bandwidth efficiency of AI, using the technology had become 98% cheaper than accessing a web page. This cost advantage suggests that AI might expand access to information in low-resource settings where the Internet is expensive.

The capabilities of AI are another crucial determinant of its impact. It is hard to predict how these will evolve, but researchers can try to anticipate how humans might respond to more-powerful systems. Even as technology advances, human behaviour tends to follow stable patterns — in terms of how people develop trust, how they respond to incentives and how they adapt to automation.