You have full access to this article via your institution.

George Hanna.Credit: EAES

Diagnosing pancreatic cancer at an early stage is challenging. The signs and symptoms — including abdominal pain, weight loss and indigestion — are often non-specific and shared with benign diseases. In England, 39% of people receive a diagnosis only once the cancer has spread to other areas of the body, such as the liver or lungs. George Hanna, an oesophageal surgeon and head of Imperial College London’s department of surgery and cancer, spoke to Nature about a breath test designed to detect the malignancy early.

Why are you developing a breath-based test?

I was inspired by nature. I knew that dogs could smell cancer by detecting chemical changes produced by molecules exhaled by their owners. I wondered if we could mimic this. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) — the most common form of pancreatic cancer — is diagnosed using imaging, such as computed tomography (CT) scans, and biopsies, which are invasive procedures. The whole process can often take weeks. In the United Kingdom, only people who meet strict referral guidelines for cancer can be tested, which excludes people with vague symptoms. And, at the time of diagnosis, fewer than 10% of people with pancreatic cancer still qualify for surgery, which is the only curative option.

Nature Outlook: Pancreatic cancer

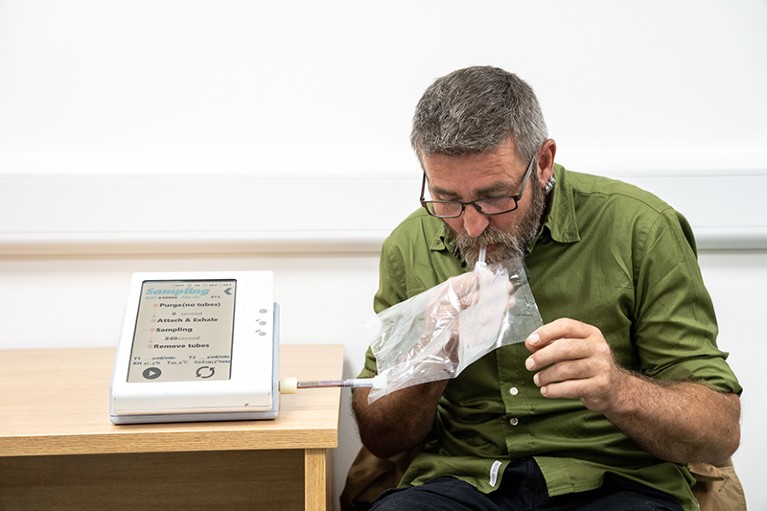

But if someone walks into a hospital or a pharmacy complaining of any of the vague symptoms that are indicative of PDAC, then they could do a breath test right there. It takes about five minutes to do, and the aim is that results would be available within 24 hours of reaching the laboratory. If it’s positive for PDAC, the person is referred for further testing to confirm the result. The breath test is quick, easy and non-invasive, and if we can use it to find people with PDAC earlier, then they would have more treatment options and a better chance of surviving. Modelling studies show that using the breath test this way could save the UK National Health Service £155 million (US$202 million), annually.

How does the test work?

The test works like an alcohol breathalyser. The person breathes into a sterile bag. The breath sample is then transferred into a tube that contains a sorbent, which traps molecules known as volatile organic compounds (VOCs). This tube is then taken to the lab, and its contents are analysed for specific compounds using mass spectrometry.

The breath test for PDAC looks for VOCs that come from the cancer itself, the response of the body to cancer (which is present at an early disease stage) and the bacteria associated with the cancer. These bacteria are different from those found elsewhere in the body and they produce unique VOCs during metabolic processes. Some of the VOCs help us to discriminate between cancer and no-cancer, whereas others are specific to pancreatic cancer. Our model looks at the compounds in the sample and suggests whether it is cancer or not.

A breath test for pancreatic cancer, which involves breathing into a sterile bag, is in development.Credit: Jeff Moore/Pancreatic Cancer UK

How is development going?

With the funding we received initially in 2007, we spent three years trialling the test at St Mary’s Hospital, London, and then another three years conducting a multi-centre study in London. After another five years developing the methodology, the first part of our trial started in 2022. We invited more than 700 people from 18 medical centres across the United Kingdom to take the test. The participants also underwent a CT scan or a biopsy, to give us a reference diagnosis. We used this to construct the model, and then used internal validation to assess the test and model. The first part of the trail has just finished. Early results show that the approach is promising. The charity Pancreatic Cancer UK, which is one of our funders, announced £1.1 million in further funding for the project on 29 October.

What has been the biggest challenge in developing the test so far?

The question was how could we scale it up for a national roll out and maintain quality. We have to make sure that we don’t lose compounds from samples. Any of the VOCs can be lost at any stage. For example, if the tubes are not capped correctly, or if they are not stored at the appropriate temperature. Compared with a blood sample, preventing contamination is more difficult, the transport of it is more difficult and the analysis is more difficult. Working on something you can’t see is complicated.

How are you ensuring that this test will work for as many people as possible?

We must make sure that our study participants reflect the UK population. We have chosen study sites that cover the whole range of deprivation indices in the United Kingdom. These indices measure the relative socio-economic status of different areas. This does not mean that the participants will come from these areas, but at least the probability that they will is high. We also have an engagement plan focused on minority ethnic groups and people with disabilities to encourage them to participate in the research.

What’s next for your research?

We began a validation study in October, which will run until the end of 2028 and recruit roughly 6,000 people. This is the part of the trial in which people do the breath test before they have a diagnosis. We’ll then compare what our test reveals to the diagnosis that they receive through the standard channel. We are also developing breath tests for multiple other cancers of the gastrointestinal tract, and we hope to test 30,000 people with these cancers in the next three years. I hope that at some point we will combine everything and be able to use one test for multiple gastrointestinal cancers. This is a challenge, but I enjoy making something that is difficult, workable. The ‘impossible’ just takes a little longer.