The idea that science should shape public policy is under serious attack. The massive funding cuts requested this year by the administration of US President Donald Trump, affecting US universities and leading scientific and research institutions, is one drastic demonstration. But there have been straws in the wind for some time.

How did assaults on science become the norm — and what can we do?

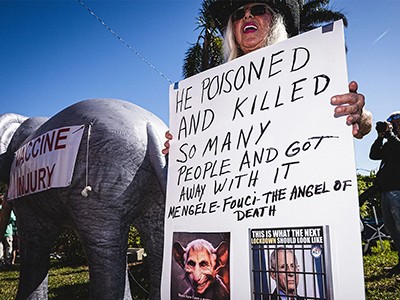

Conspiracy theories spread by people opposed to vaccines and 5G mobile phone networks, and claims that the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change are hoaxes, tell us that scientific evidence has lost its standing among parts of the public and some politicians. This trend threatens to derail the contributions science can make to improving people’s lives. Think, for example, of the announcement in August that US funding for mRNA vaccine research would be slashed.

How to meet this challenge must be a priority for researchers and the institutions of science in 2026. Rebuilding support for evidence-based policymaking among voters and political decision makers will require researchers and universities to change their outlook and ethos. Academics must recognize that the importance of science is not self-evident, and that part of the blame for the erosion of trust in science lies with scientists themselves.

Here, we offer four recommendations for the scientific community and one for policymakers.

Mixed results

‘Evidence-based policymaking’ is talked about and championed by many policymakers and scientists. Yet, the process it entails and its limitations remain widely misunderstood. In public policy, solutions to the problems society faces are rarely, if ever, purely technical. People’s values and interests often conflict, and scientific studies do not always provide direct answers to the questions that politicians and officials must grapple with, such as how to reduce crime rates or respond to a disease outbreak.

The idea of evidence-based policy was taken forward vigorously after the end of the Second World War, especially in the United States, following the wartime success of science and operations research1. An influential 1945 report called ‘Science, The Endless Frontier’, by engineer and science administrator Vannevar Bush, put science at the heart of shaping government priorities2. Since then, most policy professionals have been trained to accept that good public policy is the outcome of the rational analysis of a robust evidence base. But that’s not as straightforward as it sounds.

Government decisions around the timing, design and implementation of policies are infused with political considerations. And those political choices can often override the science — a truth laid bare during the pandemic. For example, the UK COVID-19 inquiry summarized last month how scientific advice had little influence on the chaotic decisions being made by the then government. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s decision to post on its website that “the claim ‘vaccines do not cause autism’ is not an evidence-based claim” is another (ironic) example of politics trumping science.

AI tools as science policy advisers? The potential and the pitfalls

In reality, the ‘truth’ around a policy problem can be uncertain. It will be contested in good faith by experts and in bad faith by lobbyists, in high stakes contexts such as whether and when to introduce a lockdown during a pandemic or mandate a switch to electric vehicles.

And it’s not always straightforward to know which kind of evidence matters most. For instance, policies that aim to address climate change by making fossil fuels more costly might disadvantage poorer people and add to inequality. How should the relevant social, economic and climate evidence be given their due weight? Science alone won’t answer this dilemma.

Many policymakers also kid themselves that they are making objective decisions by using quantitative tools to evaluate options. Take cost-benefit analysis, for example. The UK Treasury ‘Green Book’ offers guidance for evaluating whether a government programme is good value for money by using modelling to predict costs and benefits over many years.

The resulting figure for the ‘net present value’ of a project is used to make policy choices. But it is based on a limited set of data and leaves much out. It doesn’t tell you about the value judgements that went in, such as whether and how to include the costs of environmental damage and impacts on health, or what assumptions were made around different population groups and future generations, for example.

Target-setting is another way to make policy choices seem more objective than they are. Since the 1990s, some governments, including those of the United Kingdom, United States, Australia and Sweden, have broadly followed ‘new public management’ theory in an attempt to make their operations more efficient. Efforts are focused by setting numerical outcomes for public services, such as the proportion of pupils attaining specified grades, or the length of waiting lists for treatments.

Unfortunately, such targets often turn out to be counterproductive; they can be gamed and don’t necessarily reflect what’s actually important. For example, in 1999, the UK government set an 8-minute target for ambulance response times for the most serious calls; it was met, although through tactics such as changing the definition of calls received or altering the times that calls were recorded3.

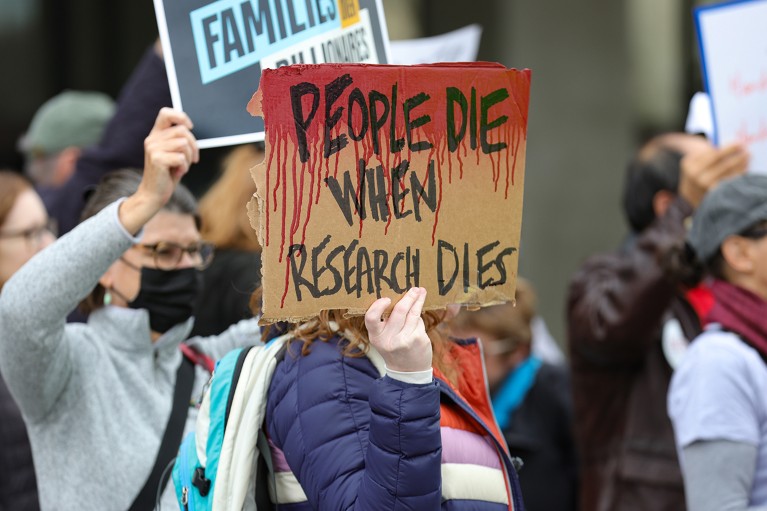

US workers protest against cuts to federal health-research budgets and staffing levels.Credit: Bryan Dozier/NurPhoto/Reuters

Now, the allure of big data and artificial intelligence as potential sources of public-sector efficiency is driving interest in the concept of ‘deliverology’4 — the latest variant of the illusion that better data ensure better policy. The cuts in federal-agency spending introduced by the US Department of Government Efficiency this year are a drastic example of the thinking that technology can optimize decisions. But many other governments, including the United Kingdom’s, are embracing similar ideas around data-driven policy.

On the face of it, it’s hard to argue with the claim that policy choices should follow the evidence. But the emphasis on defined metrics has clearly not delivered for the public, and this failure has helped to fuel public disenchantment with science. And, still, the underlying flaw of technocratic policymaking remains unaddressed: conflicts of values and interests do not have a numerical or technical answer.

Scientific evidence clearly does have a lot to offer well-informed policymaking, and the anti-science backlash needs to be addressed. The lesson from policy failures across countries since the 1990s is that the way in which scientists and suppliers of evidence and expertise engage with policy needs to change.

A deeper look

Until a decade ago, most elected politicians did generally pay lip service to the idea of policy informed by rigorous evidence. But this idea is increasingly called into question, as exemplified by the Trump administration’s policies against vaccination and against measures to tackle climate change. Like Trump, Argentinian president Javier Milei has also asserted that climate change is a “hoax” and made large cuts in research funding.

One of the main explanations for this shift, which deserves greater recognition in our view, is the chasm that has opened up between people who have attended university, and thrived economically as a result, and those who have not. Put bluntly, evidence-based policy has not delivered for the latter, despite the massive resources that governments have poured into scientific research over many decades. And that fact affects public views about science.

For example, in the United States, people with at least a four-year university degree have experienced higher income growth since 1980, with a wage premium over those without a degree climbing from 40% to about 75% by 20005. Better-educated people experience better health outcomes for illnesses such as diabetes and heart disease6.

Inequality affects places, too. In rural parts of the United States, poverty is growing and social mobility declining among people who lack degrees7. Graduates have increasingly been moving to fast-growing cities such as San Francisco in California and Boston in Massachusetts, where plenty of professional jobs are located8.

How to speak to a vaccine sceptic: research reveals what works

As a result of this deep polarization, which is apparent in many democracies, the very idea of ‘the public interest’ — a shared understanding of what will benefit the majority — is fragmenting. People’s values or beliefs about issues such energy or migration policy, as reflected in opinion polling, are diverging to such an extent that the very idea of policies designed to serve the public good prompts widespread scepticism.

Academics such as us, based in an elite higher-education institution, must ask ourselves whether the reasoned, evidence-based approach is more likely to serve the interests of some social groups and demographics over others.

Although it is tempting to blame increased political polarization on social-media bubbles or biased mass media, beneath this trend sits the erosion of shared experiences and common values, observed by Robert Putnam in his 2000 book Bowling Alone, for example. So although trust in science remains moderately high — for example, a large multicountry survey in 2022–23 found that 57% of respondents agreed that most scientists are honest9 — trust in the institutions that make policy decisions is in decline, especially among those with less formal education. A 2023 survey across the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development found that just 40% trusted their government to use the best evidence in decision-making10, and general trust in government has been declining since about 2000 (see go.nature.com/4ryvpdw).

There has been a good deal of soul-searching in the scientific community about such issues. But, rather than hoping that politicians and the public will see the error of their ways and rediscover the merits of evidence-based policymaking, we suggest that scientists and universities need to respond to these dynamics in proactive and creative ways.

Scientists and researchers must recognize that the evidence they produce can be only part of what policymakers must take into account, and we should all be more open about this. A better understanding of the societal and political context for policy decision-making would make for greater humility, improved communication and a more effective role for research and evidence.