Sampling

The MFD sample collection includes samples collected as part of the MFD sampling campaign, as well as samples contributed by members of the MFD consortium. The samples taken as part of the MFD sampling campaign were registered and associated with the appropriate metadata using codeREADr (https://www.codereadr.com) using a linear barcode attached to sterile 100 ml sample containers. After collection, the samples were stored between 4 °C and 10 °C for up to 48 h before being deposited at −20 °C for later processing.

As we wanted to cover as much of the Danish environmental landscape as possible, we requested expert collaborators send existing samples from interesting environments or environments that are not easily sampled. These include samples from existing publications, samples collected as part of governmental monitoring, but also samples from collaborators with no current publication. If not otherwise stated, these samples were acquired as frozen sample material. We divided each set of samples into projects, in which samples of the same type (soil, sediment, water) were subjected to the same treatment. Based on this, we constructed summary tables over the different protocols used for sampling and DNA extraction methodology (Supplementary Data 5). Most samples (across the biggest sample groups) were treated similarly, but we acknowledge that the different treatments might affect the results; consequently we applied the appropriate filtering where needed. The number of subsamples and other related sampling metadata are provided at GitHub and in Supplementary Data 6.

Soil samples

Topsoil samples from the MFD sampling campaign were collected as up to five subsamples (0–20 cm), taken within a ∼80 m2 (5 m radius) sampling area using a weed extractor, which was cleaned with 70% ethanol between sampling sites. As DNA from microorganisms could potentially be overwhelmed by the DNA from whole specimens in the sample material, we visually inspected each subsample with the naked eye and avoided including complete specimens (grass, leaves, sticks or larger animals) in the samples. After specimen removal on site, the subsamples were combined in a sterile plastic bag, the bag closed and the collective sample homogenized by hand before up to 100 ml was transferred to the barcoded sample container (P04_2, P04_4, P04_6, P04_7, P08_1, P08_2, P08_3, P08_5, P08_6, P08_7, P08_8 and P17_1). The samples from projects P19_1, P20_1, P21_1 (ref. 64) and P25_1 were collected as single subsamples. The subset of topsoil samples from the Land Use and Coverage Area Frame Survey (P04_8)25 were collected by collaborators from Aarhus University as described in previously65, in a manner very similar to the MFD sampling campaign.

A subset of the topsoil samples (P01_1)31 from both natural and agricultural habitats were provided by collaborators from Aarhus University and Copenhagen University. These were collected as described previously31. In brief, 81 subsamples, spanning a 9 × 9 grid covering a 40 × 40 m plot, were mixed into a representative sample from which we acquired a subsample. New sample projects were added to extend the existing project with wet terrestrial habitats (P01_2), agricultural and semi-agricultural habitats (P02_1), sites with different agricultural practices (P02_2 (ref. 66)) and urban habitats (P03_1 (ref. 67)). These were all collected as 81 subsamples except in the case of P03_1 which was mixed from 9 subsamples.

Samples from subterranean soils were collected as single samples from different depths using a soil drill (P06_1, P06_2, P06_3). Subsurface soil (P06_1) was collected with PVC liners by percussion hammering using a Geoprobe (NIRAS) drill rig. Soil samples were then collected around the oxic-anoxic interface with 5 ml cut-off syringes through openings cut into the core liners. We acquired the samples from P06_3 as DNA, which had previously been extracted using the DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In the case of agricultural soils from croplands, six out of every seventh sample was provided by SEGES. As part of the collection, the individual samples were frozen, crushed to particles below 1 cm in size and dried at 37 °C (P04_3, P04_5), the effect of which was investigated (Supplementary Note 3).

Sediment samples

Surface sediment samples (0–10 cm) from the MFD sampling campaign were collected as up to five sediment subsamples from across the sampling area using a gravity corer, which was cleaned with 70% ethanol between sampling sites. The subsamples were combined in a sterile plastic bag, the bag was closed and the collective sample was homogenized by hand after careful removal of larger debris and any collected water. Up to 100 ml of the homogenized sample was transferred to the barcoded sample container. For the sediment from standing water sources (P05_1, P05_2, P08_5, P09_1, P09_2, P11_1 and P11_3) the top 10 cm was collected, while only the top 5 cm was collected from streams (P10_1, P10_2 and P10_3). Pond sediment (P09_2) was collected from the deepest point of each pond. Stream samples were collected as three subsamples across a 20 m transect of the stream, two at 25% distance from each brim and one in the middle of the stream.

Lake sediments provided by University of Southern Denmark were from either lakes selected for investigation of biotic phosphorus dynamics (P09_3) or a lake restauration initiative (P09_4). For P09_3, the cores were taken from the deepest part of the lake. For P09_4, the cores were taken at five different sampling stations. In both cases, a gravity corer was used for the sampling68. Sediment samples from coastal areas (P11_2) were collected at a single point using a HAPS bottom corer, as described previously69. Each sample was mixed from 10 subsamples of the sediment core (0–2 cm and 5–7 cm). We acquired the samples as DNA, which had previously been extracted with the DNeasy PowerMax Soil Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

We acquired DNA extracts from Aarhus University from multiple sampling campaigns of marine surface and subterranean sediments (P12_1 (ref. 70), P12_2 (refs. 71,72)). P12_1 holds samples from the Bornholm Basin stations BB01 (13–63 cm) and BB03 (19–73 cm) sampled with a Rumohr corer. Samples from P12_1 were previously extracted with the DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol while phenol-chloroform-isoamyl-alcohol extraction was used for P12_2. We expanded this sample category with sediments from the Baltic Sea provided by WSP Denmark (P12_5). Top sediments (0–30 cm) were collected using a HAPS bottom corer while subterranean sediments (0–300 cm) were collected using a Vibrocore sampler.

Water samples

Besides the samples from fjords (P11_3) the diversity in the natural environments found in the soil and sediment categories is not reflected in this category. The water category is instead made up of samples with a link to the urban environment: drinking water from the waterworks stage (P16_1 (ref. 73), P16_3 (ref. 74)), tap water (P16_1), potentially polluted groundwater (P16_4) and samples from wastewater treatment plants (P13_1 (ref. 75), P13_2 (ref. 75)).

Water samples from fjords (P11_3) were collected with a 1 l Ruttner water sampler. The sampler was rinsed three times with water from the locality before the water samples were collected. At each sampling location, five 1 l water samples were randomly collected. The water samples were transferred to 5 l cleansed plastic bottles and stored in a cooler (< 8 h) until they could be filtered in the laboratory. At stations with a halocline, water samples were collected from both above and below the halocline and were treated as two separate events. The collected water was filtered through a mixed cellulose ester membrane (47 mm, 0.22 µm) by dead-end filtration using a sterile filter funnel and a vacuum pump. The amount of water filtered for each sampling site varied from 0.3 l to 1 l. Filters were stored at −20 °C before DNA was extracted using the DNeasy PowerWater Kit (QIAGEN), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples of drinking water (2 l) from the drinking water treatment plants (P16_1) were filtered through a mixed cellulose ester membrane (47 mm, 0.22 µm). The amount of water filtered varied from 0.25 l to 1.8 l. Tap water (5 l) was filtered through a cellulose acetate membrane (47 mm, 0.22 µm). The amount of water filtered varied from 4 l to 5 l. In both cases, filtering was performed as dead-end filtration using a sterile filter funnel and a vacuum pump and the filters were stored at −20 °C before DNA was extracted from the filters using the DNeasy PowerWater Kit (QIAGEN), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The samples in P16_4 of probable polluted ground water (1 l) were filtered through a cellulose nitrate membrane (47 mm, 0.22 µm) by dead-end filtration using a sterile filter funnel and a vacuum pump. The amount of water filtered varied from 0.5 l to 1 l. Filters were stored at −20 °C before DNA was extracted from the filters using the DNeasy PowerLyzer Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

The Technical University of Denmark provided DNA extracted from concentrates. Samples were taken from raw water (abstracted groundwater), filtered water (after secondary sand filters), treated water (after ultraviolet treatment) and water from the distribution network (P16_3). Between 100 l and 250 l of water from the different sampling points was pumped through separate REXEED 25S filters at a constant rate. After sample elution (200 ml) from the REXEED filter, a secondary concentration was conducted using VivaSpin 15R (SATORIUS) filters and centrifugation at 3,500g. DNA was extracted from 100 µl of final concentrate using the NucliSens miniMAG platform and NucliSens Magnetic Extraction Reagents (bioMerieux) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples from wastewater treatment plants were included as DNA samples extracted with the FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals). Wastewater was sampled as both influent (P13_1), using flow proportional sampling, and activated sludge from the aeration tank (P13_2) as described previously75.

Other samples

We included a last group of samples to encompass the samples that did not directly fit into either of the soil, sediment and water categories. This category covers samples from various surfaces in harbours (P18_1 and P18_2), sand filter material from drinking water treatment plants (P16_2 and P16_3), sludge from anaerobic digesters (P13_3), and scrapings from the walls of a limestone mine and a salt vat (P25_1). The harbour samples (P18_1 and P18_2) were collected as individual scraped-off biofilms and biocrusts from a range of different surfaces (such as fenders and piers). Each sampling location is associated with three individual samples. Sand filter material in P16_2 was collected as described previously76. The pooled medium samples were made by homogenizing and combining 20 g subsamples from 20 cm depth intervals. For P16_3 the sand filter material (around 15–40 ml) was collected from 1–2 locations at the top of 12 groundwater-fed rapid sand filters of 11 Danish waterworks using a 1% hypochlorite-wiped stainless-steel grab sampler. Samples from anaerobic digesters (P13_3) were collected from 20 digesters across Denmark, with DNA extracted using the standard DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (QIAGEN) according to published protocols20.

Subsampling and DNA extraction

Unless otherwise stated in the precious sections, DNA extraction was performed as previously described77. The sample containers were thawed at 4 °C and dried soil samples were rehydrated using phosphate-buffered saline before subsampling. The sample material was divided into a total of three Matrix 1.2 ml 2D barcoded tubes (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Of the three 2D Matrix tubes only one was prefilled with the lysing matrix E (MP Biomedical), to which 100 µl of sample material was added. For the two other tubes, 800 µl of sample material was added and deposited at −20 °C in the MFD biobank. The tubes destined for downstream DNA extraction were added to a 96-well SBS rack containing 4 empty positions, 4 reaction blanks and 1 extraction positive control (https://github.com/SebastianDall/HT-Downscaled-Illumina-Metagenomes-Protocol). Linkage of the linear barcodes of the original sample container, the 2D Matrix tubes and location in the final SBS racks was ensured with the use of a Mirage Rack Reader (Ziath) and the software DataPaq (Ziath) forwarding the entries to an SQL server (MongoDB). Pseudolinks were generated for samples acquired as DNA extracts.

DNA extraction was performed using slightly modified protocol of the DNeasy 96 PowerSoil Pro QIAcube HT Kit (QIAGEN). In total, 500 µl CD1 was added to each 2D barcoded Matrix tube; the samples then underwent three 1,600 rpm bead-beating cycles performed at 2-min intervals using the FastPrep-96 (MP Biomedicals). Between the cycles, the samples were kept on ice for 2 min. After lysis, the samples were centrifuged at 3,486g for 10 min using an Eppendorf 5810 benchtop centrifuge (Eppendorf). Then, 300 µl supernatant was transferred by hand to a new S-block containing 300 µl CD2 and 100 µl nuclease-free water (NFW) to meet the requirement of 700 µl for the remaining part of the protocol. The samples were mixed by pipetting and centrifuged at 3,486g for 10 min; the sample transfer step was then performed using the QIAcube HT. All of the subsequent steps were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA was quantified using the Qubit 1× HS assay (Invitrogen). Extraction metadata, including a denotation of methodology, can be found in Supplementary Data 6.

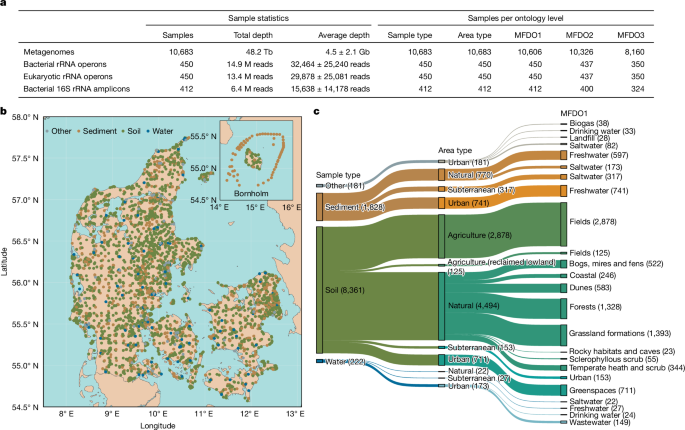

MFD ontology

For the MFD data, habitat classification was performed on site by experts in accordance with the relevant field guides when available for the habitats (that is, the natural habitats from macrobial ontologies). Habitat classification was therefore performed by checking the presence of plant indicator species, topographic and abiotic conditions. The MFDO was developed as a link between the classical plant-derived habitat ontologies and the Earth Microbiome Project Ontology (EMPO). The broadest MFDO classification level (Sample type), corresponds to the most specific EMPO level (EMPO level 4)3, while the detailed levels for natural samples correspond broadly to the Natura 2000 habitat ontology8. Finally, missing categories, such as urban, were adapted from the EUNIS ontology9 to provide a detailed description of non-natural habitats. The MFDO was designed, for the moment, to fit the Danish environment and it was refined with a panel of national experts. The full MFDO and its association to other habitat ontologies (that is, EMPO, Natura 2000 and EUNIS) can be found at GitHub (https://github.com/cmc-aau/mfd_metadata).

Metadata curation

The metadata collected with codeREADr were screened for completeness in the following fields (hereafter, minimal metadata): fieldsample_barcode (the unique sample identifier), project_id (unique identifier of the subproject), longitude and latitude (ISO 6709), sitename (common name of the sampling site), coords_reliable (indicating if the coordinates are reliable, not reliable or masked), sampling_date (sampling date ISO 8601) and five levels of the MFD habitat ontology (mfd_sampletype, mfd_areatype, mfd_hab1, mfd_hab2, mfd_hab3). If a sample presented an incorrect entry, (for example, wrong format, not meaningful for that column or unreadable), the error was corrected using R78 v.4.2.3, and if a correction was not possible, or the entry absent, the responsible person for the subproject was contacted. The process was iterated until improvements were not possible anymore. In brief, common corrections included case changing, date formatting (using lubridate79, v.1.9.2) and coordinate projection (project function from terra80, v.1.7.55). The reference grid mapping and masking of the coordinates were performed using the terra80 v.1.7.55 package. The European Environment Agency 1-km (ref. 81) and 10-km (ref. 82) reference grids of Denmark were projected from EPSG:3035 to EPSG:4326 (function project), whilst the coordinates from MFD samples were encoded into a spatial vector (function vect) and mapped onto the grids (function intersect) to identify their cells of origin. The cells associated with each sample (when the coordinates were present), were reported in the fields cell.1 km and cell.10 km of the metadata. The centroids of the cells were computed (function centroids) and, in the case of samples from subprojects P04_3 and P04_5, the centroids were provided as latitude and longitude, while the coords_reliable field for those samples was set to ‘Masked’. Coordinates from subproject P06_3 were provided already masked as generic locations in the commune of sampling. Concordance between manual annotation of the habitat and government-registered LU (land use) designation was inferred comparing the MFDO for each sample with the Basemap04 (ref. 10) aggregated LU map. A broad correspondence of terms between MFDO and LU terms was established and, to account for GPS and labelling inaccuracies, any match in a range of 20 m was considered in concordance. Samples that were in disagreement were screened manually on Google Maps and, if the disagreement was confirmed, the coords_reliable field was set to ‘No’. For Fig. 1, the base map was from EuroGeographics. This dataset includes Intellectual Property from European National Mapping and Cadastral Authorities and is licensed on behalf of these by EuroGeographics. The original dataset is available for free online (https://www.mapsforeurope.org). Terms of the licence are available at https://www.mapsforeurope.org/licence. All attribution statements can be found online (www.mapsforeurope.org/attributions). For Extended Data Fig. 1, the base of the map is from Eurostat (Geodata, GISCO, Eurostat; https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/gisco/geodata).

Short-read metagenomic library preparation, sequencing and processing

Metagenomic libraries were prepared with a 1:10 reagent volume reduction of the standard Illumina DNA prep protocol (Illumina) as described previously77. Using the I.DOT One (DISPENDIX), 3 µl of up to 20 ng template DNA was prepared before addition of 2 µl BLT/TB1 and subsequent incubation in a thermocycler at 55 °C for 10 min. Tagmentation was stopped by addition 1 µl TSB using the I.DOT One, and incubation in the thermocycler at 37 °C for 15 min. The tagmented DNA was washed twice with 10 µl TWB. The I.DOT One was used to add the PCR master mix, prepared by mixing 2 µl EPM and 2 µl NFW per reaction. The epMotion 96 (Eppendorf) was used to add 1 µl IDT Illumina UD index (Illumina) to each reaction well. The input of genomic DNA was used to determine the applied cycles of the BLT-PCR program: 7 (4.9–20 ng), 8 (2.5–4.9 ng), 10 (0.9–2.5 ng) or 14 (< 0.9 ng). Size-selection was performed on the libraries by addition of 17 µl NFW, before 18 µl of the reaction volume was transferred to a new PCR-plate together with a mixture of 16:18 µl SPB:NFW. After incubation, 50 µl of the supernatant was transferred to a new PCR-plate with 6 µl undiluted SPB. After incubation, the beads were washed twice with 45 µl 80% ethanol and eluted in 20 µl NFW. SPB are 1:1 interchangeable with CleanNGS SPRI beads (CleanNA).

The individual libraries were quantified using a 1:10 diluted upper standard. The pooled libraries were concentrated using 2× volume of SPRI ProNex Chemistry (Promega) beads. Final sequencing libraries were produced by an equimolar combination of the pooled libraries. Quality control was performed using the Qubit 1× HS assay (Invitrogen) and DS1000 or DS1000 HS ScreenTape (Agilent Technologies). Library metadata are provided in Supplementary Data 6.

Metagenomic libraries were sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform to a median depth of 5 Gb. If a library yielded insufficient data, the library was either repooled or reprepared for a second round of sequencing. The Illumina data were demultiplexed using bcl2fastq2 v2.20.0 (Illumina). The raw reads were trimmed for barcodes, quality filtered and deduplicated with fastp83 v.0.23.2 with the following options: –detect_adapter_for_pe –correction –cut_right –cut_right_window_size 4 –cut_right_mean_quality 20 –average_qual 30 –length_required 100 –dedup –dup_calc_accuracy 6. Commands were parallelized using GNU-parallel84 v.20220722 and outputs compressed using pigz85 v.2.4. Sequencing metadata are provided in Supplementary Data 6.

Nearly full-length bacterial 16S rRNA gene amplicon library preparation, sequencing and processing

A representative set of 426 samples were selected for 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing. These samples comprise 130 samples from the BIOWIDE project (P01_1)31, as well as 295 samples manually selected to reflect the sample diversity in the full dataset while attempting to maintain the geographical coverage. From samples from subterranean sediments (P12_1), the input DNA was pooled based on the sediment core the samples were derived from. From 14 of the samples, we failed to generate data of sufficient quality leading to a dataset of 412 samples. Here PCR was used to amplify the region V1–V8 of the 16S gene using UMI-tagged target primers enabling downstream chimera filtering and error-correction similar to the method described previously11. All of the samples were tagged by the UMI-tailed target primers lu_16S_8F and lu_16S_1391R in a PCR reaction (Supplementary Data 7). The reaction contained 10–20 ng DNA input, 1× SuperFi buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 500 nM of each primer and 2 U of Platinum SuperFi DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen) in a total volume of 50 µl. The PCR program consisted of initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min followed by 2 cycles of denaturation (95 °C for 30 s), annealing (55 °C for 1 min) and extension (72 °C for 5 min). The PCR products were then purified with CleanNGS SPRI beads (CleanNA) at a ratio of 0.7× beads per sample. After 5 min of incubation, the beads were washed twice in 80% ethanol and eluted in 18 µl NFW for 5 min. The tagged molecules were then amplified in a second 25 cycle PCR reaction using barcoded primers targeting the UMI-adapter sequence. The PCR reaction contained 15 µl of the purified eluate, 1× SuperFi buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 500 nM of forward and reverse primer and 2 U of Platinum SuperFi DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen) in a total volume of 50 µl. The PCR-program consisted of initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min followed by 25 cycles of denaturation (95 °C for 15 s), annealing (60 °C for 30 s) and extension (72 °C for 3 min), followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR products were purified with CleanNGS SPRI beads (CleanNA) as described above and eluted in 20 µl NFW. Poorly performing samples underwent a third PCR reaction with 5–10 cycles using up to 50 ng amplicon DNA as input and otherwise identical to the previous PCR reaction.

The barcoded amplicons were multiplexed in pools of 5–6 samples containing a total of 300 ng. The pools were used as input for library preparation for DNA sequencing using the ‘Amplicons by Ligation (SQK-LSK110)’ protocol (version: ACDE_9110_v110_revG_10Nov2020) and loaded onto a MinION R.9.4.1 flow cell (FLO-MIN106D). The flow cells were sequenced for up to 72 h on a GridION platform (Oxford Nanopore Technologies) using the MinKNOW software v.21.05.8 and basecalled using the super-accurate model (r941_min_sup_g507) with Guppy v.5.0.11. Downstream consensus sequences were generated using the longread_umi pipeline v.0.3.2 described previously11 with slight modifications to ensure compatibility with the updated medaka model (r941_min_sup_g507) and the custom barcode sequences. The quality of the consensus sequences was evaluated based on a ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community DNA Standard (Zymo Research, D6306) included together with the samples. With UMI sequence coverage of ≥7× corresponding to Q30+ and ≥14× to Q40+. The exact command used to generate the consensus sequences was: longread_umi nanopore_pipeline -d input.fq -v 10 -o analysis -s 140 -e 140 -m 1000 -M 2000 -f GGAATCACATCCAAGACTGGCTAG -F AGRGTTYGATYMTGGCTCAG -r AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATC -R GACGGGCGGTGWGTRCA -c 3 -p 2 -q r941_min_sup_g507 -t 20 -T 2 -U “3;2;6;0.3”.

Bacterial and eukaryotic rRNA gene operon library preparation, sequencing and processing

A representative set of 450 samples was selected for both bacterial and eukaryotic rRNA operon sequencing. These samples are the same as those selected for 16S rRNA UMI amplicon sequencing. However, all extracted DNA had been used up for 8 of the samples, resulting in an overlap of only 404 samples, which is why we included 46 other samples. For bacterial rRNA sequencing, PCR was used to amplify around 4,500 bp targeting the 16S and 23S gene using the primers MFD_16S_8F and MFD_23S_2490R (Supplementary Data 7). For eukaryotic rRNA, operon sequencing PCR was used to amplify around 4,500 bp targeting the 18S and 28S gene using the primers MFD_18S_3NDF and MFD_28S_21R (Supplementary Data 7). The PCR reactions contained 10–20 ng DNA input, 1× SuperFi buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 500 nM of each primer and 2 U of Platinum SuperFi DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen) in a total volume of 50 µl. With the addition of 1× SuperFi GC enhancer when amplifying the eukaryotic rRNA operons. The PCR-program consisted of initial denaturation at 98 °C for 1 min followed by 25 cycles of denaturation (98 °C for 15 s), annealing (55 °C for 15 s) and extension (72 °C for 3 min), followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR products were then purified with CleanNGS SPRI beads (CleanNA) at a ratio of 0.7× beads per sample. After 5 min of incubation, the beads were washed twice in 80% ethanol and eluted in 20 µl NFW for 5 min. The amplicon DNA was barcoded in a second 8–10 cycle PCR reaction using barcoded primers targeting the introduced adapter sequence. The PCR reaction contained 20 ng of the purified amplicon DNA, 1× SuperFi buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 500 nM of forward and reverse primer and 2 U of Platinum SuperFi DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) in a total volume of 50 µl. With the addition of 1× SuperFi GC enhancer when amplifying the eukaryotic rRNA operons. The PCR program consisted of initial denaturation at 98 °C for 1 min followed by 8–10 cycles of denaturation (98 °C for 15 s), annealing (60 °C for 15 s) and extension (72 °C for 3 min), followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR products were purified with CleanNGS SPRI beads (CleanNA) as described above and eluted in 18 µl NFW.

The barcoded amplicons were multiplexed in pools of 92 samples containing a total of 1–2 µg of DNA. The pools were size-selected using SPRI ProNex Chemistry (Promega) with a ratio of 1.2× beads per sample according to the manufacturer’s protocol and eluted in 125 µl. The size-selected and purified pools were shipped for PacBio CCS sequencing on the Sequel II platform (Pacific Biosciences) using the binding kit 3.2. The CCS sequences were further processed using Lima v.2.6.0 (Pacific Biosciences) to filter and demultiplex the data. This was done using the hifi-preset ASYMMETRIC and the following settings –min-score 70, –min-end-score 40, –min-ref-span 0.75, –different, –min-scoring-regions 2. Furthermore, remaining ligation products were removed by identifying partially remaining adapter sequences after filtering. Subsequently all reads were oriented while removing primer sequences and filtering reads below 3.5 kb or above 6.5 kb using cutadapt86 v.3.4. 16S rRNA genes corresponding to the V1–V8 region were extracted from the rRNA operons using a custom script (trim_RNA_operons.sh) that carries out several steps: first, the rRNA operons were truncated to 1,450 bp using the usearch87 v.11 command fastx_truncate -trunclen 1450. The trimmed sequences were then trimmed based on the 1391R88 (Supplementary Data 7) primer using cutadapt86 v.3.4. The sequences for which the primer could not be found were aligned to the global SILVA v.138.1 SSURef NR99 (ref. 19) alignment using SINA89 v.1.6.0, the aligned sequences were trimmed according to the position of the primer binding sites in the alignment. Truncated sequences were removed using a custom script (remove_incomplete_seqs_from_sina_aln.py) that considered sequences that start or end with three or more gaps as truncated. Finally, gaps were removed using the custom script (Remove_gaps_in_fasta.py), whereafter the primer- and alignment-trimmed sequences were combined.

Before diversity analysis, 18S rRNA genes, corresponding to the position between the 3NDf90 and 1510R91 primer-binding sites (Supplementary Data 7), were extracted using a custom script (trim_euk_RNA_operons_3ndf-1510R.sh). This script was identical to the script used for processing bacterial rRNA operons except that sequences were trimmed based on the 1391R88 primer (Supplementary Data 7) with cutadapt86 v.3.4 and the alignment trimmed based on the corresponding position in the SILVA19 global alignment using SINA89 v.1.6.0. The resulting reads were dereplicated using usearch87 v.11 command usearch -fastx_uniques -sizeout and then resolved into ASVs using usearch -unoise3 -minsize 2. The phylogenetic diversity of the 18S rRNA genes was determined by clustering the ASVs into OTUs at 99% identity with usearch -cluster_smallmem -maxrejects 512 -sortedby other, followed by mapping against the PR2 (ref. 16) database to determine the percentage identity with the closest hit in the database using usearch -usearch_global -maxrejects 0 -maxaccepts 0 -top_hit_only -id 0 -strand plus. An OTU-table was created by mapping the trimmed raw reads against the 99% OTUs using usearch -otutab -otus. Taxonomy was assigned to the OTUs using the UTAX version of the PR2 database16 v.5.0.0, the SINTAX classifier through usearch63,87 v.11. For 18S diversity analyses, the taxonomy was inferred with the DADA2 (ref. 92) v.1.26.0 function assignTaxonomy. OTUs not classified as Eukaryota were discarded before the downstream analyses.

Estimation of the Danish terrestrial diversity

The nearly full-length 16S rRNA UMI gene sequences were mapped against the nearly full-length OTUs clustered at 98.7% sequence similarity to yield a dataset (OTU table) with 412 habitat-representative samples and 107,826 (106,760 after filtering) species-representative OTUs using usearch87 v.11 with downstream analysis done in R78 v.4.4.1 using tidyverse93 v.2.0.0. Similarly, the full-length 18S rRNA gene sequences were mapped against the nearly full-length OTUs clustered at 99% sequence similarity, yielding a dataset of 450 habitat-representative samples and 12,515 (12,469 after filtering) species-representative OTUs.

We made habitat-specific rarefaction curves across samples with more than 4,000 observations from habitats with more than 9 sample representatives (5.9 million observations), as well as a pan-habitat rarefaction curve (6.0 million observations) from the nearly full-length bacterial rRNA gene UMI dataset. For this analysis, we combined the samples from temperate heath and scrub (n = 12) and sclerophyllous scrub (n = 7). Likewise, we made habitat-specific rarefaction curves across samples with more than 6,000 observations from habitats with more than 9 sample representatives (12.0 million observations), as well as a pan-habitat rarefaction curve (12.9 million observations) from the eukaryotic nearly full-length 18S rRNA gene dataset. For this analysis we combined the samples from temperate heath and scrub (n = 13) and sclerophyllous scrub (n = 7). Rarefaction was performed using vegan94 v.2.6-6-1 (function rarecurve) using a step size of 10,000.

Sample based coverage and Hill diversity indices were calculated after transformation to presence and absence data by using rarefaction and extrapolation with Hill numbers of order q as implemented in the iNEXT95 v.3.0.1 package (function iNEXT). Hill richness (total number of species), Hill–Shannon (number of common species) and Hill–Simpson (number of dominant species) were estimated using order q = 0, q = 1 and q = 2, respectively. For the total dataset, the end point of extrapolation was set to twice the size of the dataset (nBac = 824, nEuk = 900); and, for habitat-specific estimates, the end point was fixed at 100 samples. For the habitat-specific data, we investigated normality (function shapiro_test) of the community coverage and log-transformed sampling effort and, based on the results, measured the linear correlation with the Pearson correlation coefficient (function cor_test) using the package rstatix96 v.0.7.2.

Establishment of the MFG 16S rRNA gene reference database

The MFG 16S rRNA reference database was assembled from high-quality bacterial and archaeal 16S rRNA genes obtained from several sources: nearly full-length 16S rRNA gene and rRNA operon amplicons created in this study, SILVA v138.1 SSURef NR99 (ref. 19), EMP500 (ref. 3), AGP70 (ref. 11), MiDAS 4 (ref. 97) and MiDAS 5 (ref. 20), and ref. 21. All bacterial sequences were trimmed between the 8F98 and 1391R99 primer-binding sites (Supplementary Data 7), and archaeal sequences between the 20F100 and the SSU1000ArR101 primer-binding sites (Supplementary Data 7).

High-quality bacterial and archaeal sequences were obtained from the SILVA v138.1 SSURef NR99 (ref. 19) ARB-database by exporting them separately in the fastawide format after terminal trimming between positions 1,044 and 41,788 (Bacteria) and positions 1,041 and 32,818 (Archaea) in the global SILVA19 alignment, corresponding to the primer binding sites (Supplementary Data 7). A custom script (Extract_full-length_16S_rRNA_genes_from_SILVA_alignments.sh) was used to remove truncated sequences based on the presence of terminal gaps in the exported FASTA-alignments. Finally, sequences that contained N’s were removed and U’s were replaced with T’s using two custom scripts (Remove_seqs_with_Ns.py and replace_U_with_T.py).

Owing to the large number of trimmed 16S rRNA gene reads, ASVs were resolved for each dataset individually. Sequences were dereplicated using the usearch87 v.11 command usearch -fastx_uniques -sizeout and then resolved into ASVs using usearch -unoise3 -minsize 2. ASVs from all individual datasets were combined with the 16S sequences from SILVA v138.1 SSURef NR99 (ref. 19) and dereplicated using usearch -fastx_uniques. The ASVs were sorted based on their abundance across the MFD dataset by mapping the trimmed sequences against the ASVs with usearch -search_exact -dbmask none -strand plus -matched. The matched sequences were dereplicated using usearch -fastx_unique -sizeout, and sequences which did not originate from the MFD samples were appended. The complete database was processed using AutoTax18 v.1.7.6 to create the MFG 16S reference database. As the MFG database was found to contain sequences representing chloroplast and mitochondrial 16S rRNA genes, as well as pseudogenes, we performed additional filtering to create the final MFG database. To inform this filtering, we undertook extensive manual evaluation of the phylogenetic tree and sequence alignments in ARB102 v.7.0 to establish a reproducible method for removing non-16S rRNA gene sequences. These steps included removing (1) all sequences that shared less than 70% identity with their closest match in the SILVA v138.1 SSURef NR99 database19, as these most likely represent pseudogenes and would lead to inflated phylum level diversity; (2) ASVs with de novo placeholder names and best hits in SILVA v138.1 SSURef NR9919 against Mitochondria or Chloroplast; (3) ASVs with de novo phyla placeholder names and top hits against Rickettsiales and less than 75% identify, as these also probably represent mitochondrial sequences that are not represented in the SILVA database; (4) ASVs representing de novo phyla covered by only a single ASV; (5) ASVs with a better hit in the MIDORI2 GB257 mitochondrial database103 than in SILVA19 v138.1 SSURef NR99, which, at the same time, share >75% identity (> 1,000 bp alignment length) to the MIDORI2 GB257 (ref. 103) hit. Finally, ASVs that were assigned to de novo phyla but shared >70% identity with a Patescibacteria hit were assigned to Patescibacteria. The species-level clustered (98.7% identity) version of the MFG 16S reference database was created by subsetting the MFG 16S reference database to those representing the 98.7% clustering centroids created during the AutoTax18 processing based on their ASV numbers.

Database evaluation

To evaluate the coverage of the MFG database, we classified 16S gene fragment reads (13.1 million) extracted from representative metagenomes based on the 10 km EU reference grid of Denmark (see the ‘Spatial thinning’ section) and 16S rRNA gene V4 OTUs clustered at 99% identity (2.26 million) from the GPC project23 using our database, as well as SILVA 138.1 SSURef NR99 (ref. 19), GreenGenes2 (ref. 22) and the complete 16S rRNA database from GTDB R22034 using the SINTAX classifier63, after which, the percentage of reads classified at different taxonomic ranks was determined. The analysis was conducted using R78 v.4.3.2 using tidyverse93 v.2.0.0 and vegan94 v.2.6-6.1.

Short-read 16S rRNA gene classification

Hidden Markov models (HMM) were made from Rfam104 v.14.7 seed alignments for Archaea (RF01959), Bacteria (RF00177) and Eukarya (RF01960) using hmmbuild (HMMER105 v.3.3.2). Metagenomic reads from rRNA gene fragments were extracted from the quality-filtered metagenomic reads using the constructed models with nhmmer106 (HMMER v.3.3.2) with the settings –incE 1e-05 -E 1e-05 –noali. In the case of multiple hits for the same metagenomic read, the best domain hit was selected based on the bit-score. The 16S reads were filtered for hits within the region between position 8F98 and 1391R99 primer binding sites for Bacteria (Supplementary Data 7) and the 20F100 and SSU1000ArR101 primer binding sites for Archaea (Supplementary Data 7). The 16S reads were taxonomically annotated using the SINTAX classifier63 and the MFG 16S reference database with the confidence cutoff set to 0.8. The output was aggregated to the individual taxonomic levels using R78 v.4.4.1 and the tidyverse93 v.2.0.0 package. Reads not classified at the given taxonomic level were assigned to ‘unclassified’.

Spatial thinning

To investigate the effect of spatial autocorrelation on community composition, we performed a distance decay analysis across the levels of the MFD ontology. The spatial autocorrelation was modelled using a logarithmic decay model of Hellinger-transformed Bray–Curtis similarity (1 − Bray–Curtis dissimilarity) as a function of spatial distance. Spatial distances were calculated from longitude and latitude with the codep107 v.1.2-3 package (function geodesics) using the Haversine formula. A pseudocount of 0.1 m was added between samples with a spatial distance of zero. Community similarity was calculated using the metagenomic 16S rRNA gene fragments aggregated at the genus level from samples with more than 1,000 observations. This led to a dataset with 10,001 samples and 38.4 million observations, which was subjected to random subsampling without replacement to a depth of 1,002 observations using ampvis2 (ref. 108) v.2.8.9 (functions amp_load and amp_subset_samples). After transformation, relative abundances were Hellinger-transformed using vegan94 v.2.6-6.1 (function decostand) before calculation of Bray–Curtis dissimilarity using the package parallelDist109 v.0.2.6 (function parDist) and summarized using hexbin110 v.1.28.3. The modelling was restricted to MFDO1 habitats showing spatial separation of samples, excluded Bornholm, and was limited to spatial distances ≤300 km. These filtering criteria lead to the inclusion of 9,121 samples. We made individual models for comparisons within and between the same habitat categories across all five levels of the habitat ontology. We found that at 10 km and on the MFDO1 level and above, the spatial effect becomes negligible. To address the effect of spatial autocorrelation on community composition we made a spatially thinned dataset using the 10-km reference grid of Denmark82. For each MFDO1 habitat, we chose sample representatives by selecting the sample with the lowest mean Bray–Curtis dissimilarity to the other samples of that MFDO1 habitat in the same cell. This led to a spatially thinned subset of 2,348 samples.

Effect of drying on diversity metrics and community composition

We performed 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing of the V4 region on replicate samples originating from two different lots at an agricultural experimental station. The samples were processed as triplicates which were either subsampled the day of collection and immediately frozen and stored in the freezer for +6 months and then subsampled, or dried at either room temperature (25 °C), 40 °C, 60 °C or 80 °C overnight and then stored for +6 months. The dried samples were rewetted with PBS before subsampling and DNA extracted using the DNeasy 96 PowerSoil Pro QIAcube HT Kit (QIAGEN) as described above. We investigated normality (function shapiro_test) and homoscedasticity (function levene_test) of the amount of extracted DNA using the package rstatix96 v.0.7.2. Based on the results obtained, we chose a nonparametric approach to test the significance of the differences. We used a Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test (function kruskal_test) combined with two-sided post hoc pairwise Mann–Whitney U-test comparisons (function wilcoxon_test) from rstatix96 v.0.7.2. The Bonferroni procedure was applied to adjust for multiple testing.

DNA was diluted to 5 ng μl−1 using NFW and standard amplicon libraries were prepared as described previously77. In brief, the amplicon libraries were prepared as one 50 μl reaction, which was subsequently split into two 25 μl reactions. Then, 25 cycles of PCR were performed on the duplicate samples, which were subsequently pooled and cleaned using 0.8× CleanNGS SPRI beads (CleanNA) and washed twice with 80% ethanol and eluted in NFW. Another 8 cycles of library PCR were performed on up to 10 ng of amplicon template and cleaned with 0.8× CleanNGS SPRI beads (CleanNA). The final libraries were quantified and pooled equimolarly to produce the final sequencing libraries. Each 25 μl amplicon PCR reaction consisted of 4 μl sample/NFW (target: 20 ng DNA), 1 µl UV-treated NFW, 25 μl PCRBIO 2× Ultra Mix and 20 μl abV4-C tailed amplicon primer mix (1 μM, 400 nM final concentration). The subsequent 25 μl library PCR was prepared with the cleaned PCR template in 2 μl sample/NFW (target: 10 ng DNA), 0.5 µl NFW, 12.5 μl PCRBIO 2× Ultra Mix (PCR Biosystems) and 10 μl adapter indexes (4 μM). After clean-up, libraries were pooled equimolarly. A detailed protocol can be found at GitHub (https://github.com/SebastianDall/HT-downscaled-amplicon-library-protocol).

The final library was sequenced on the Illumina MiSeq platform. ASV abundance tables were generated by running AmpProc v.5.1 (https://github.com/eyashiro/AmpProc) using the following choices: standard workflow, generate both otu and zotu tables, process only single-end reads, no primer region removal, amplicon region V4 and no taxonomic assignment. The 16S reads were taxonomically annotated using the SINTAX classifier63 and the MFG 16S reference database with the confidence cutoff set to 0.8.

We filtered the data to samples with more than 10,000 observations, which led to a dataset of 35 samples out of the original 36 and a total of 1.65 million observations. We performed random subsampling without replacement to a depth of 36,975 observations using ampvis2 (ref. 108) v.2.8.9 (functions amp_load and amp_subset_samples).

We used ampvis2 (ref. 108) v.2.8.9 to investigate community composition (function amp_heatmap) and to perform exploratory ordination analysis (function amp_ordinate) using Hellinger-transformed Bray–Curtis dissimilarities of ASVs with more than 0.01% relative abundance in any sample. We used ampvis2 (ref. 108) v.2.8.9 to calculate observed ASV richness (function amp_alphadiv) and Bray–Curtis dissimilarity (function vegdist) after Hellinger-transformation (function decostand) of relative abundances using vegan94 v2.6-6.1. We investigated normality (function shapiro_test) and homoscedasticity (function levene_test) of both observed ASV richness and Bray–Curtis similarity (1 − Bray–Curtis dissimilarity) using the package rstatix96 v.0.7.2. On the basis of the results obtained, we chose a nonparametric approach to test the significance of the differences. We used a Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test (function kruskal_test) combined with two-sided post hoc pairwise Mann–Whitney U-test comparisons (function wilcoxon_test) from rstatix96 v.0.7.2. The Bonferroni procedure was applied to adjust for multiple testing. We performed a PERMANOVA to access the effect of treatment on the community composition (as measured as Hellinger-transformed Bray–Curtis dissimilarity) and partitioned the variance by contrasts using vegan94 v.2.6-6.1 (function adonis2). In both cases 9,999 permutations were used.

Evaluate the variable treatment effect in agricultural soils from MFD

We selected samples in the metagenomic 16S rRNA gene fragment dataset from either the pool of dried samples (n = 2.617) or frozen samples (n = 385) but excluded the frozen samples from lowland soils. To ensure spatial separation, we selected the representative samples from the spatially thinned subset while considering the different type of crops. This procedure led to the selection of 30 dried and 30 frozen samples. The sampling points were visualized on a map of Denmark using the ggplot111 extension ggspatial112 v.1.1.9 and the base map from rnaturalearth113 v.1.0.1. We performed a principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of Hellinger-transformed Bray–Curtis dissimilarities. Principal coordinate decomposition performed with the ape114 v.5.8 package (function pcoa). We evaluated dispersion of the habitats using vegan94 v.2.6-6-1 (function betadisper). The significance of the overall dissimilarity between habitats was evaluated using ANOSIM (function anosim) using vegan94 v.2.6-6-1 with 9,999 permutations. We performed a PERMANOVA to access the effect of treatment on the community composition using vegan94 v.2.6-6.1 (function adonis2) with 9,999 permutations.

Diversity metrics

Based on the sampling methodology and DNA extraction summaries, we limited the analysis of diversity metrics to surface sediment and topsoil from environments with a minimum of nine sample representatives. We filtered the data to samples with more than 4,000 and 6,000 reads in the nearly full-length 16S rRNA gene UMI dataset and the nearly full-length 18S rRNA gene dataset respectively. For the diversity calculations, we combined the samples from ‘temperate heath and scrub’ and ‘sclerophyllous scrub’. We performed random subsampling without replacement to a level of 4,008 and 6,235 for the 16S and 18S rRNA gene data, respectively using vegan94 v.2.6-6-1 (function rrarefy). After this procedure, the nearly full-length 16S rRNA UMI dataset comprised 309 habitat-representative samples, 76,052 species-representative OTUs and 1.2 million observations, while the numbers for the nearly full-length 18S were 363 samples, 10,356 species representative OTUs and 2.2 million observations. Finally, the nearly full-length 18S rRNA gene data were transformed to presence and absence.

For the prokaryotic communities, the beta diversity was evaluated from the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrix (see the ‘Spatial thinning’ section) calculated from the metagenome-derived 16S rRNA gene fragment dataset. After subsetting to the spatially thinned set of samples and filtering to the environments used in analysis of alpha and gamma diversity, the matrix encompassed dissimilarities between 1,954 samples. For the eukaryotic communities, we calculated Jaccard dissimilarity on the nearly full-length 18S rRNA using the package parallelDist109 v.0.2.6 (function parDist) due to sparsity of 18S rRNA gene reads in the metagenomic data.

Alpha diversity was calculated as observed OTU richness using ampvis2 (ref. 108) v2.8.9 (function amp_alphadiv). We investigated normality (function shapiro_test) and homoscedasticity (function levene_test) of the groups using the package rstatix96 v.0.7.2. Owing to multiple cases of non-normality, a nonparametric approach was applied. Significance of differences in the observed richness was statistically tested using a Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test (function kruskal_test) and two-sided post hoc pairwise Mann–Whitney U-test comparisons (function wilcoxon_test) from rstatix96 v.0.7.2. The Benjamini–Hochberg procedure was applied to adjust for multiple testing. A compact letter display was made using the function multcompLetters from package multcompView115 v.0.1-10 using a confidence threshold of 0.05. Gamma diversity was estimated after transforming the prokaryotic data to presence and absence, by using rarefaction and extrapolation with Hill numbers of order q as implemented in the iNEXT95 v.3.0.1 package (function iNEXT). The end point of extrapolation was fixed at 100 samples and gamma diversity reported as Hill–Shannon using order q = 1. Differences between groups were inferred from the 95% confidence intervals. Beta diversity was evaluated at both mean within-habitat and mean between-habitat level. Differences in beta diversity were visualized using the stats78 v.4.4.1 package (function hclust, method ward.D2) on the between-habitat Bray–Curtis dissimilarities, with the confidence of the habitat-splits calculated using 100 iterations with the bootstrap116 v.0.1 package (function bootstrap). The analysis was conducted using R78 v.4.4.0 using tidyverse93 v.2.0.0.

Exploratory PCoA

We explored differences in community composition between different habitats by performing PCoA on the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrix calculated from the metagenome-derived 16S rRNA gene fragment dataset (see the ‘Spatial thinning’ section) and from the Jaccard dissimilarity matrix of nearly full-length 18S rRNA gene dataset of presence and absences. For the prokaryotic metagenomic-derived data, we removed samples from subterranean environments, samples from drinking water treatment plants and habitats with less than 20 sample representatives, the matrix encompassed Bray–Curtis dissimilarities between 9,643 samples. For the nearly full-length eukaryotic data, we used the same data as for calculations of alpha and gamma diversity resulting in a matrix of Jaccard dissimilarities between 363 samples. Principal coordinate decomposition was performed with the ape114 v.5.8 package (function pcoa). We evaluated dispersion of the habitats using vegan94 v.2.6-6-1 (function betadisper). The significance of the overall dissimilarity between habitats was evaluated using ANOSIM (function anosim) using vegan94 v.2.6-6-1 with 999 permutations. To evaluate how much of the variance could be explained by the MFDO1 habitat levels we performed a PERMANOVA (function adonis2) using vegan94 v.2.6-6-1 with 999 permutations. We expanded the analysis using a contrasts analysis also using adonis2 and 999 permutations.

Habitat classification

The habitat classification analysis was performed using R78 v.4.2.3 according to the workflow described in Supplementary Note 5. The microbial relative abundances at the genus level of the 16S gene fragments were summarized at higher taxonomic levels (family to phylum) by summing up the abundances of populations with the same taxonomy. Taxa observed with a relative abundance >0 in at least 25 samples were retained for subsequent analysis. The resulting five tables were screened for multicollinearity using the function vifcor (th = 0.7) from the package sdm117 v.1.1_18 wrapped in a block-wise script for efficiency. Considering the block-wise implementation, it is not guaranteed to find the optimal solution, but the shuffling at each iteration increases the chances of approaching it. The microbial data were filtered for a minimum (n = 25) of species observations, spatially thinned (by habitat class) with a minimum distance of 5 km using the function thin_by_dist from tidysdm118 v.0.9.5. The ontology was used to create five different target variables, one for each ontology level, but only classes with at least 50 observations and whose class names were not ending with ‘NA’ were retained for modelling. The modelling was carried out with the package tidymodels119 v.1.1.1, which allows the creation of model workflows. The functions cited in this section belong to tidymodels119 or its dependencies unless otherwise stated. The data were split (stratified by class) in training and test set (70/30 split) using the function initial_split and, in the training data (70% of the filtered set), the minority classes were upsampled using the SMOTE algorithm from the package themis120 v.1.0.3 with a ratio equal to 0.5. The predictor variables (microbial relative abundances) were centred on the mean, scaled to unit variance and used to build a random forest model (from the package ranger121 v.0.16.0). The models’ hyperparameters mtry, trees and min_n were tuned using a fivefold cross validation using the function vfold_cv with v = 5 and repeats = 5; leading to 25 fits from fit_resample and an equal number of evaluation points per hyperparameters’ combination. The best model was selected and evaluated on the test set (30% of filtered data). Moreover, the variable importance (impurity) was retrieved for the best model. Several steps in the workflow involve random choices (Supplementary Note 5), therefore, to smoothen the effects of randomness, the workflow was repeated 25 times starting from the spatial thinning. Global metrics such as F1 (micro and macro), PR-AUC and Kappa were collected after the validation using the function collect_metrics. We collected a total of 25 best models, one for each combination between predictors (phylum, class, order, family, genus) and targets (sample type, area type, MFDO1, MFDO2, MFDO3). The analysis of the false negatives was performed by collecting, for each class in each fold and iteration the number of associated misclassified samples, using the function conf_mat from the package yardstick122 v.1.3.0. A null distribution of false negatives was computed by multiplying the previous number by the fraction of samples in each class (except for the class in exam). A two-tailed paired t-test was performed using the function t_test from the package rstatix96 v.0.7.2.

Core analysis

Abundant and prevalent genera were identified from the spatially thinned dataset across each level of the MFD ontology using a prevalence and relative abundance filter of 50% and 0.1% respectively. Investigation of shared genera was performed using UpSetR123 v.1.4.0 and ComplexUpset124 v.1.3.3. We screened the core genera for candidates related to habitat disturbance and visualized their abundance and prevalence across the different MFDO1-level habitats. We mapped all 16S rRNA genes from metagenomic bins (see below) against the MFG 16S reference database (98.7% identity) using usearch87 v.11 usearch_global, with the flags -top_hits_only and -strand both. We then identified genera associated with nitrogen cycling and investigated their abundance and prevalence across the MFDO1 habitats.

Metagenomic assembly and binning

Trimmed shallow metagenomic reads were assembled using MegaHit125 v.1.2.9 with the following options: –k-list 27,43,71,99,127 –min-contig-len 1000. Metagenomes smaller than 1 Mb were omitted from further processing. In total, 10,042 assemblies were used for genome recovery.

To maximize the recovery of low coverage MAGs, the SingleM40 v.1.0.0beta7 ‘pipe’ subcommand with the default GTDB R214 metapackage126 was first run on the metagenomes to generate archive OTU tables of single-copy marker gene sequences (combined with SingleM summarize across all samples). Bin Chicken127 v.0.9.6 was then run on those tables using the command ibis coassemble –max-coassembly-samples 1 –max-recovery-samples 10 –singlem-metapackage S3.2.1.GTDB_r214.metapackage_20231006.smpkg.zb, to match the single-copy protein sequences across samples and choose the 10 most similar samples for each sample for multisample binning. The reads for the selected samples were mapped to the assemblies using Minimap2 (ref. 128) v.2.24 with the -ax sr option and SAMtools129 v.1.16.1 with samtools view -Sb -F 2308 – | samtools sort options. The jgi_summarize_bam_contig_depths command of MetaBAT2 (ref. 130) v.2.12.1 was used on the mapping files to acquire contig coverage values, which were used as input for binning through MetaBAT2 (ref. 130) with the following options: -m 1500 -s 100000.

The recovered MAGs were quality-assessed using CheckM2 (ref. 131) v1.0.2 to acquire MAG completeness, contamination values and were taxonomically classified using GTDB-Tk132 v.2.4.0. Bakta133 v.1.8.1 with Bakta database v.5.0 (type full) was used to annotate the MAGs and acquire bacterial rRNA and tRNA counts, while for archaeal MAGs, tRNAscan-SE134 v.2.0.9 and barrnap135 v.0.9 with the corresponding archaeal databases were used to acquire tRNA and rRNA counts. CheckM2 (ref. 131) completeness and contamination values, together with the observed rRNA and tRNA counts, were used to classify the MAGs according to MIMAG136 guidelines, and only medium- or high-quality MAGs were kept for further analysis. The MAGs were dereplicated using dRep137 v.2.6.2 with the -sa 0.95 -nc 0.4 settings. MAG coverage values were calculated using CoverM138 v.0.6.1, with the -m mean setting.

Representation of the metagenomic microbial community by these short-read-assembled MAGs in each sample was assessed using SingleM40 v.0.18.0 (default GTDB R220 reference metapackage139 v.4.3.0) through the appraise subcommand that compares the OTUs of 59 single-marker copy genes found in the metagenomic reads and MAGs. In brief, the SingleM pipe subcommand was first applied to individual trimmed short-read metagenomes (with a minimum of 100 bp) and individual short-read assembled MAGs to identify OTU sequences of these 59 marker genes in both types of datasets. For each type of dataset (that is, short-read data and MAGs), OTU tables were then combined using SingleM summarize and passed through the SingleM appraise subcommand (under the default cut-off for species-level estimates) to compare the OTU tables of both data types for determining the bacterial and archaeal community recovered by the short-read assembled MAGs.

For ‘Candidatus Nitrososappho danica’ and ‘Candidatus Nitronatura plena’, we conducted a targeted reassembly to retrieve the highest quality possible genome representatives for the type material. Long-read assemblies of MFD06229 (containing ‘Candidatus N. natura’) and MFD09848 (containing ‘Candidatus Nitrososappho danica’) were taxonomically classified with mmseqs2 (ref. 140) v.14.7e284 using the uniref100 database141 (12 October 2024 download date). For reassembling MFD06229.bin.1.58 (NCBI: GCA_974707355.1), reads mapping to contigs classified as the Nitrospirota phylum were extracted using the Samtools129 v.1.20 “view -q 20 -m 1000” command and assembled with myloasm142 v.0.1.0. The acquired circular contig was extracted as a separate genome bin. For MFD09848.bin.1.115 (NCBI: GCA_974504955.1), reads mapping to contigs of the Nitrososphaerota phylum were extracted with the Samtools view -q 20 -m 1000 command and assembled using Flye143 (v.2.9.3) with the following settings: –nano-hq, –meta, –extra-params min_read_cov_cutoff = 12. A MAG was then recovered through manual binning and curation by comparing the reassembled contigs to the original MFD09848.bin.1.115 genome.

Novelty and prokaryotic fraction estimation

To assess sample novelty in each shallow metagenome, microbial profiles were estimated by SingleM40 v.0.18.0 (default GTDB R220 reference metapackage v.4.3.0) using the SingleM pipe subcommand. Essentially, OTUs of 59 single-copy marker genes were first identified from the shallow metagenomes and compared against those found in the reference genome database to assign taxonomic classifications for the identified OTUs. The overall taxonomic profile for each metagenome was then condensed from the OTU tables of all the different markers. Sample novelty was expressed in terms of the proportion of microbial community characterized by the current reference genome database that encompassed most recent advances in genome mining. This was achieved by taking the ratio between the sum of the total coverage at the species level and the sum of total coverage at all taxonomic levels based on the condensed taxonomic profiles (hereafter, known species fraction). To compare novelty between metagenomes from MFD and NCBI public metagenomes, published SingleM40 profiling results for NCBI datasets were used for comparison with the MFD datasets. NCBI datasets were grouped into NCBI_Water, NCBI_Soil, NCBI_Sediment and NCBI_Human based on the original metadata labelling in the original SingleM publication using the habitat mapping in Supplementary Table 3. NCBI_Human refers to the human gut metagenomes in NCBI, and they were used as a reference point for a well-studied system.

To investigate the improved species representation of the microbial community by the short-read assembled MAGs, the MAGs were added to the default GTDB R220 SingleM metapackage139 v.4.3.0. This was done using the SingleM supplement subcommand applying dereplication at 95% similarity and CheckM2 (ref. 131) quality filtering of 50% completeness and 10% contamination for all MAGs to be supplemented. In total, 4,507 dereplicated and novel species representatives from 19,253 MFD MAGs were added to the new metapackage. The microbial community was then reanalysed based on this new metapackage supplemented with the short-read constructed MAGs using the SingleM renew subcommand.

Genome quantification

We quantified the microorganisms across Denmark using the MFD MAG catalogue as reference and the full set of short-read metagenomes with sylph41 v.0.6.1. First, we indexed the reference and the samples using the sketch command and the default parameters. The command profile was used to profile the sample sketches against the genome sketches. We extended the microbial taxonomy from GTDB34 R220 to include the dereplication cluster identifier calculated by dRep137 v.2.6.2 (see the ‘Metagenome assembly and binning’ section). We incorporated the microbial taxonomy using the utility script sylph_to_taxprof.py and then extracted the quantification matrices with the utility script merge_sylph_taxprof.py. The taxonomic abundance was aggregated from individual genome to species clusters in R78 v.4.2.3 using the tidyverse93 v.2.0.0 package. For analysis of genome abundances of AOA species cluster TA-21 sp02254895 cluster 98_1, one sample was randomly selected from each 10 km reference cell within each MFDO3 level. Only MFDO3 levels represented in at least 10 different 10 km reference cells were included in the analysis, to exclude habitat types only being present in a confined area of Denmark. We investigated normality (function shapiro_test) and homoscedasticity (function levene_test) of the groups using the package rstatix96 v.0.7.2. Owing to non-normality, a nonparametric approach was applied for comparison of groups. Pairwise comparison was performed between each group (MFDO3) against all (base mean) using a one-sided Mann–Whitney U-test (function wilcoxon_test).

Gene-centric investigation of short-read metagenomes

A dereplicated set of the species representatives from the GTDB34 release 214 and the genomes from Earth’s microbiomes4 GEM database was created using fastANI144 v.1.32 removing all GEMOTU genomes with >96% average nucleotide identity over >50% aligned fragments to a GTDB34 species representative. The resulting 97,227 genomes (85,205 GTDB and 12,022 GEMOTU) were annotated using anvi’o145 v.8 with gene calling using Prodigal146 v.2.63.

The total protein complement of the 97,227 genomes was used as a query in a DIAMOND147 v.2.1.8 search against preliminary protein datasets of cytoplasmic NarG/NxrA, the two distinct versions of periplasmic NxrA/NarG (exemplified by Nitrospira and Nitrotoga, respectively), and AmoA/PmoA with a score cut-off of 100. True-positive hits were selected using an alignment score ratio approach as previously described148,149, resulting in 1,068 AmoA/PmoA sequences, and 10,254 cytoplasmic NxrA/NarG sequences, 665 periplasmic NxrA/NarG sequences of the Nitrospira clade, and 581 periplasmic NxrA/NarG sequences of the Nitrotoga clade. To search the short-read metagenome data for AmoA and NxrA/NarG functional genes, we created several new GraftM39 v.0.14 search packages: Archaeal AmoA, Bacterial AmoA, cytoplasmic NxrA/NarG and periplasmic NxrA/NarG. The AmoA/PmoA sequences were split into 823 bacterial and 245 archaeal sequences to create two specific GraftM packages. Moreover, the two periplasmic NxrA/NarG sequence databases were combined to make one GraftM package.

Multiple-sequence alignment of protein sequences was performed with MAFFT150 v.7.490. TrimAl151 v.1.4.1 was used to trim minimum 20% amino acid representation. IQ-TREE152 v.2.2.0.3 was used to generate phylogenetic trees of protein sequences, using the ultrafast bootstrap approximation option and 1,000 iterations. For NxrA/NarG and bacterial AmoA trees, the ModelFinder153 option was applied (best-fit models pNXR: LG + R6, cNXR: LG + F + R10, Bacterial amoA: LG + F + R8). The model applied for the archaeal AmoA tree was WAG + R. ARB102 v.7.0 was used to reroot and group trees, followed by visualization in iTOL154 v.6. Trees used for GraftM39 v.0.14 package generation are shown in Supplementary Fig. 10. Inclusion of protein sequences of NxrA and AmoA obtained through this study was filtered based on length of the protein product, with a cut-off of 200 amino acids for AmoA and 600 amino acids for NxrA. Gene phylogeny was ascertained using GraftM39 v.0.14 on the forward shallow metagenomic reads with search mode hmmsearch+diamond along with a conditional E-value threshold of 10−10. The samples were filtered to include at least 500,000 reads (Supplementary Note 9). The output was aggregated to the individual clades using R78 v.4.4.1 and the tidyverse93 v.2.0.0 package. A full overview of all clades without aggregation is shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. Read abundance was normalized by HMM-alignment length (bacterial AmoA: 744 nucleotides, archaeal AmoA: 648 nucleotides, pNXR: 3,411 nucleotides, cNXR: 4,092 nucleotides) reported in RPKM. To reduce the complexity and describe the habitats with interesting nitrifier distributions, only the major soil types from MFDO1 habitats ‘soil, agriculture, fields’, ‘soil, natural, bogs, mires and fens’, ‘soil, natural, forests’, ‘soil, natural, grassland formations’ and ‘soil, urban, greenspaces’ were included in the main analysis. Agricultural samples from reclaimed lowlands were included in the ‘soil, agriculture, fields’ category. Analysis of the remaining habitats is provided in Supplementary Note 9. Read abundances were Hellinger-transformed using vegan94 v.2.6-6.1 (function decostand) before calculation of Bray–Curtis dissimilarity with the package parallelDist109 v.0.2.6 (function parDist) and performing the principal coordinate decomposition with the ape114 v.5.8 package (function pcoa). Samples were clustered within MFDO2 habitats using hierarchical clustering with the stats78 v.4.4.1 package (function hclust, method=ward.D2). As the MFDO2 for samples within ‘soil, natural, forests’ was not descriptive, being either ‘temperate forests’ or ‘forest (non-habitattype)’, the MFDO3 was used in the clustering of forest samples. A least squared distance linear model was used to calculate the linear correlation between RPKM of Nitrospira clade B amoA (dependent variable) and Palsa-1315 nxrA (independent variable) using the stats78 v.4.4.1 package (function lm). Spearman’s rank correlation was calculated using stats v.4.4.1 package (function cor.test).

Linkage of AOA MAGs to the major terrestrial amoA clades

The nucleotide sequences of all full-length amoA genes encoded in the 890 AOA genomes in the GlobDB155 (release 220) were exported using anvi’o145 (v8 development version). These 679 amoA sequences were combined with the 1,206 amoA sequences in the dataset from ref. 46 and aligned with Muscle5. The alignment was trimmed by removing the first 128 and last 41 positions using TrimAl151 v.1.5.0 to only include the 591 aligned positions used to create the phylogeny of ref. 46. A phylogeny was calculated based on the trimmed alignment with IQ-TREE152 v.2.4.0 using the GTR + F + I + R10 model selected by ModelFinder153. The GTDB R220 taxonomy of the GlobDB genomes encoding amoA sequences was matched to the amoA clades by manually inspecting the phylogeny. For the terrestrial Nitrososphaeraceae, the genera assigned by GTDB-Tk132 v.2.4.0 directly corresponded to the specific clades in the amoA phylogeny defined previously46. A translation table for the amoA and GTDB taxonomies of the Nitrososphaeraceae is provided in Supplementary Data 3. For the Nitrosopumilaceae (including the Nitrosotalea genus), a direct translation between amoA clades and GTDB genera could not be made for all clades defined in either amoA or concatenated marker gene phylogenies due to incongruencies in the topologies of the amoA and concatenated marker gene phylogenies.

Phylogenomic investigation of nitrifier genera, and Nitrobacter-like NxrA containing MAGs compared to NxrA gene phylogeny

We identified MAGs encoding Nitrobacter-like NxrA sequences of at least 600 amino acids in length within the family Xanthobacteraceae genera BOG-931, Bradyrhizobium, JAFAXD01, Pseudolabrys and VAZQ01. The MAGs encoding Nitrobacter-like NxrA sequences were selected for phylogenetic analysis, alongside species that belonged to the genus level GTDB34 R214 groups BOG-931, Bradyrhizobium, JAFAXD01, Pseudolabrys and VAZQ01, and also met the >90% genome completeness and <5% genome contamination thresholds using CheckM2 (ref. 131) v.1.0.2. The single recovered Nitrobacter MAG from this study was also included, as well as representatives from GTDB34 R214 for context, for example, the species representatives present for BOG-931, JAFAXD01, VAZQ01 and manually selected isolates from Bradyrhizobium and Pseudolabrys. The specific Nxr groups were assigned based on the updated GraftM package and classification tree. The phylogenomic tree was constructed using GTDB-Tk132 v.2.3.2 and the de_novo_wf on all bacterial MAGs. The multiple-sequence alignments of 120 single-copy proteins were subset to the genomes of interest using fxtract156 v.2.3. This alignment was used as input for IQ-TREE152 v.2.1.2 using the WAG + G model and -B 1000 using UFBoot. The tree was visualized in ARB102 v.7.0 for rerooting by the Methylopilaceae isolate outgroups and analysis, and further processed in iTOL154 v.6.

The cytoplasmic NxrA tree was built using Nitrobacter-like NxrA sequences of at least 600 amino acids in length from Xanthobacteraceae-family MAGs, along with known NxrA from Nitrococcus and Nitrobacter, and outgroup NxrA sequences from Nitrospira, Scalindua and Brocadia. Alignment, trimming and tree-generation was done using MAFFT150 v.7.490, TrimAl151 v.1.4.1, IQ-TREE152 v.2.2.0.3 with ultrafast bootstrap approximation and 1,000 iterations, using substitution model LG + F + R10.

Phylogenomic trees for known nitrifier genera as well as the putative genera examined in this study were created by subsetting the GTDB-Tk de_novo_wf trees for the bacteria and archaea. Trees were investigated and refined using ARB102 v.7.0 and iTOL v.6 as above, with final refinements in Inkscape v.1.4.2.

Metabolic investigation of nitrifier MAGs

Metabolic reconstruction of the short-read MAGs was conducted using DRAM157 v.1.4.6 and the KEGG database158 release 109. DRAM.py annotate was run using the default settings, followed by DRAM.py distil. Key nitrification and Calvin–Benson–Bassham-cycle genes were searched based on KO identifiers in the DRAM annotations.tsv output file and incorporated into the genome trees. Gene synteny was displayed using R78 v.4.4.1 and the gggenes111 v.0.5.1 package. To annotate carbohydrate active enzymes, dbCAN HMMdb159 v.13 (released 14 August 2024) was used on the dbCAN3 webserver, and hits were filtered (E < 10−15, coverage >0.80) as described previously48. Peptidases were identified with DRAM based on the MEROPS peptidase database160 (downloaded 1 July 2024) and were filtered to not include any hits to unassigned peptidases or non-peptidase homologues.

Data exploration and visualization

Data analysis was conducted in RStudio 2024.04.2 and 2023.12 using R78 v.4.2.3 to v.4.4.0 using tidyverse93 v.2.0.0. Data were read with either data.table161 v.1.15.4 or readxl162 v.1.4.3. Summary statistics are either reported as median or as mean ± s.d. where applicable. The colour scale for the MFOD1 levels of the ontology was made using wesanderson163 v.0.3.7. To ensure that continuous gradients were colour blind friendly, colours from viridisLite164 v.0.4.2 were used. Plots were made using ggplot from tidyverse93 v.2.0.0, patchwork165 v.1.2.0, ggpmisc166 v.0.5.6, ggpubr167 v.0.6.0 and ggtext168 v.0.1.2 and combined using Adobe Illustrator 2024 and Inkscape v.1.4.2.

Sample permissions

All necessary permits for sample collection were obtained before fieldwork. All samples were collected within the Danish Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ); therefore, the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit-Sharing does not apply. The Danish EEZ does not include any indigenous territories; accordingly, the CARE (collective benefit, authority to control, responsibility, and ethics) principles were not applicable to this work.

Etymology

Description of ‘Candidatus Nitronatura plena’ gen. nov., sp. nov.:

‘Candidatus Nitronatura plena’ (ni.tro.na.tu’ra. From L. neut. n. nitrum, nitrate, and N.L. fem. n. natura, nature; N.L. fem. n. Nitronatura, meaning ‘nitrogen and nature’, symbolizing a lineage associated with nitrogen cycling in natural ecosystems; ple’na. L. fem. adj. plena, full or complete, referring to the capacity for complete ammonia oxidation by clade B comammox). This taxon is represented by the circular closed Nitrospiraceae MAG GCA_974707355.1, recovered from a sphagnum acid bog. The complete protologue is provided in Supplementary Data 8.

Description of ‘Candidatus Nitrososappho danica’ gen. nov., sp. nov.:

‘Candidatus Nitrososappho danica’ (ni.tro.so.sap’pho. From L. masc. adj, nitrosus, full of natron, here intended to mean ‘nitrous’; and N.L. fem. n. Sappho, latinized form of the Greek poet’s name Σαπφώ. N.L. fem. n. Nitrososappho, is used here as a metaphor for resilience and persistence, in this case, of an archaeal ammonia oxidizer found in environmentally disturbed or constrained habitats; da’ni.ca. N.L. fem. adj. danica, Danish, referring to the origin of the sample and wide distribution in Denmark). This taxon is represented by the archaeal MAG (comprising 8 contigs) GCA_974504955.1, recovered from the sediment of an urban rainwater basin; however, the species is also widely present in agriculture. The complete protologue is provided in Supplementary Data 8.

The proposed names were registered at SeqCode under the register list seqco.de/r:xueh5m88.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.