San Jose was flooded in 2017 when storm water in Coyote Creek was funnelled into the city.Credit: Noah Berger/AFP via Getty

Coyote Creek’s waters rose fast in February 2017 amid a series of storms. Rainfall filled the small river in northern California, which runs 103 kilometres from its headwaters near Morgan Hill to San Francisco Bay. In San Jose, where the river was forced into a channel tightly constrained by development, water surged from the creek. The resulting flooding forced 14,000 people to evacuate and caused more than US$73 million of damage.

In the wake of the disaster, environmental activists opposed to San Jose’s sprawl into Coyote Valley on the city’s southern edge saw an opportunity. Their plan was to convince San Jose officials that the city could avoid worse flooding by choosing not to pave over some of the last open space in the watershed.

Nature Outlook: Cities

Their approach has solid scientific roots. When land is paved, rain cannot soak into the soil, increasing the risk of flooding. One study1 found that, for every 1% increase in the area of roads, pavements and car parks, the annual flood magnitude in nearby waterways increases by 3.3%.

A growing understanding of this connection has led many cities to start de-paving small areas, digging and planting bioswales to absorb storm-water run-off, offering incentives for green roofs, and levying higher taxes on properties with a lot of impervious surface area. But the proposal by San Jose’s environmentalists was different. Their aim was not to make the city itself more permeable to water, but to reduce the risk of flooding by taking action upstream in the watershed, beyond the city’s urban footprint.

The 2017 flood provided the impetus to act. In the following year, San Jose’s voters approved a bond for about half of the $93 million required to buy 380 hectares of North Coyote Valley. “I don’t think we would have considered putting it on the ballot, or even considered that flooding was an issue, until we were devastated by the water damage in San Jose,” says the city’s current vice-mayor, Pam Foley.

The city of San Jose and conservation organizations have invested more than $120 million in purchasing 600 hectares of land in north and mid Coyote Valley. In 2021, the city council voted unanimously to change the land-use designations for the area, effectively barring any new development.

San Jose’s conservation of Coyote Valley reflects how land care is increasingly seen as crucial to managing flood risk. This marks a radical departure from the twentieth-century approach of trying to engineer water into submission. Conventional flood defences might also be needed, but San Jose is not alone in adopting more-natural methods of water management.

More than climate

As the climate warms, the atmosphere can hold more water. In San Jose, this is causing both more-intense droughts and larger storms bringing heavy rain — a recipe for damaging floods. But climate change is not the only culprit behind the increased flooding and losses, says Dominik Paprotny, a geographer at the University of Szczecin in Poland. “It’s always assumed that the flood losses are going up and it’s due to climate change,” he says, but in reality “it’s a complex, human-related process”.

In August, Paprotny and colleagues published a study2 breaking down the various drivers of flood risk across Europe. They found that development that degrades the environment is “more relevant than climate change” in causing flood losses, he says.

Since 1992, cities around the world have built homes and businesses on floodplains spanning an area the size of Ukraine. This development encourages people to move into harm’s way. Floodplains exist to absorb floods, so people living on them are highly likely to encounter water damage sooner or later.

The fact that people continue to build in places that are likely to flood is partly the result of misaligned incentives, says Paprotny. Insurance companies and national governments typically compensate flood losses, or individual property owners take the hit. Developers and local authorities are rarely on the hook. “For them, there is only the benefit,” he says.

In the city of Szczecin, Paprotny has seen numerous tower blocks built in a formerly marshy area of the Odra River. He expects them to experience flooding as the rise in sea level increases. About 100 kilometres downriver, the coastal town of Międzyzdroje has approved a residential building right on the beach. “Local authorities have fantasies of building everything, everywhere,” Paprotny says.

Short-sighted planning and the expansion of paved areas are not the only factors that increase a city’s flood risk. Healthy soil contains more than half of Earth’s species, including microorganisms, springtails, arachnids, worms and fungi, which turn their mineral home into a matrix that absorbs vast amounts of water. But both inside the city limits and in the wider watershed, pesticides used in lawns and industrial agriculture are killing these creatures, decreasing the soil’s ability to hold water.

The good news is that flood managers have much more agency over the local environment than they do over global climate change.

Restoring rivers

Throughout history, cities have sprouted along waterways. As residents and industry polluted the rivers and the demand for centralized real estate grew, cities across the world have followed a standard development plan: fill in wetlands and creeks, or bury them in underground pipes, and then build on top. The small percentage of urban waterways that remain at the surface have typically been straightened, in a misguided attempt to avoid flooding by speeding the water away. The subsequent scouring and erosion prompted people to protect the banks with sandbags or concrete.

Milwaukee’s Kinnickinnic River went through this transformation in the 1960s. Its watershed, one of six that run through the Milwaukee metropolitan region into Lake Michigan, is the most heavily urbanized in Wisconsin. In the past few decades, straightening and paving rivers has fallen out of favour globally, says Bill Graffin, public-information manager for the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District (MMSD), which serves more than 1 million people.

Curves, rocks and vegetation are being reintroduced to Milwaukee’s Kinnickinnic River.Credit: Bill Graffin

Conventional concrete flood control narrows the space for water and accelerates the flow through rivers. This makes them dangerous in storms. “When they’re full, they’re extremely powerful and fast-moving: 20 feet per second, with a pressure of 400 to 500 pounds,” Graffin says. Milwaukee has seen numerous drowning deaths. “If you fall in, there’s a good chance you’re not getting out.”

As climate change brings more-severe deluges, concrete channels cannot cope. “It’s the intensity that really throws a wrench into urban planning,” says Graffin. A storm in mid-August this year brought 37 centimetres of rainfall in one area of the county, with an average of 25 centimetres over a 24-hour period. “We got nailed,” he says. The subsequent flooding damaged public infrastructure and more than 4,500 homes and commercial buildings, causing $76 million in damages. Building concrete solutions that can deal with the increased volume from the biggest rainfall events “can get very, very, very costly”, Graffin says. “Green infrastructure can be done cost-effectively.”

With that in mind, Milwaukee is expanding the volume for flood waters by restoring the Kinnickinnic River to a more natural state. The MMSD is beginning to remove the industrial flood channel and revive more natural aspects to the river, such as reintroducing curves, rocks and streamside vegetation, in eight projects along the waterway and 12 more in its wider watershed.

The plan, which is projected to cost $496 million, is to expand the lateral space for water, allowing it to slow down. To make space, the MMSD has acquired 83 nearby properties. According to Graffin, there was little opposition from owners because their homes had repeatedly flooded, year after year. “They were thankful to see us knock on the door,” he says.

Like San Jose, Milwaukee is also looking beyond the city’s footprint to make space for water. Its Green Seams programme is buying undeveloped land, often in natural wetlands. “As soon as we make that purchase, we put that conservation easement onto the land so that it can’t be developed,” says Graffin. The roughly 2,300 hectares of land protected so far, at a cost of $30 million, can store more than 11 billion litres of water. By contrast, a 26-hectare flood storage basin in the city cost $100 million and can hold only 1.2 billion litres.

Reverse engineering

An economic study3 by the non-profit organization Resources for the Future, based in Washington DC, bears out the efficacy of using natural wetlands for flood protection. The researchers found that when US communities invest in protecting a wetland, about half of them save that much money in five years by avoiding flood damages. And flood mitigation can benefit properties 50 kilometres away.

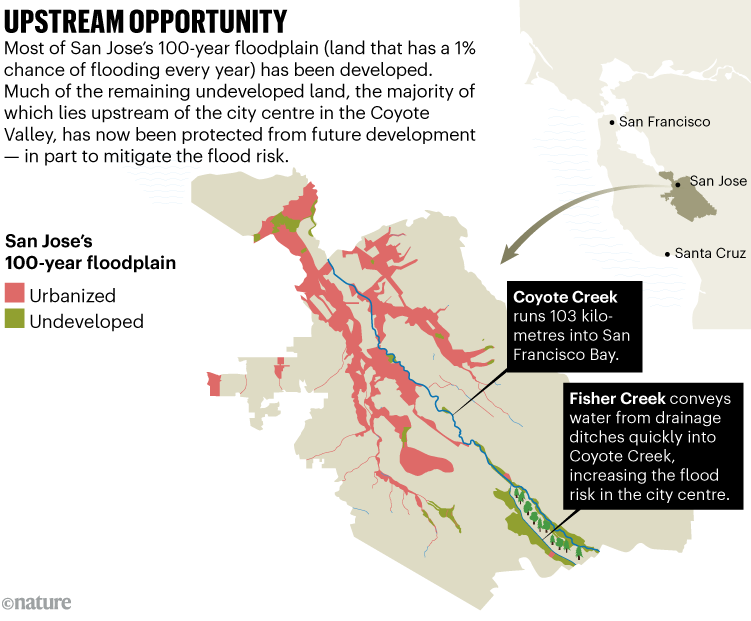

In San Jose, residents might not see such a rapid benefit. The land is still open, but previous changes made for the purposes of agriculture resulted in more water flowing into Coyote Creek. “Historically, a lot of the Coyote Valley area was actually this series of discontinuous streams and wetlands, and it didn’t have any kind of surface connection to Coyote Creek,” says Rachel Clemons, a watershed-restoration specialist at the Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority. Instead of resting on the valley floor, creating a habitat for wildlife or soaking down into the aquifer where it could find its way to Coyote Creek over a longer period of time, the water is funnelled straight into the creek and then through the centre of San Jose (see ‘Upstream opportunity’).

Engineering of the land began a century ago, by farmers who saw these seasonal wetlands as an obstacle to them growing good crops. In 1916, the farmers started digging drainage ditches leading to the creek, and laying underground tiles and gravel to route water towards the new channels. Their plan worked: water now drains quickly into the human-made Fisher Creek, which carries it swiftly on to Coyote Creek and through the city, Clemons says.

During the Silicon Valley boom in the 1990s, San Jose-based Cisco Systems was considering Coyote Valley for its headquarters. It built a weir, which blocks most of the water flowing from the southern Coyote Valley into Laguna Seca, a seasonal wetland to the north. When the dot-com bubble burst in the early 2000s, Cisco Systems abandoned the project — but the small dam remains. Water that would otherwise flow into Laguna Seca is instead “shuttling to Fisher Creek directly”, Clemons says.

The Santa Clara Valley Open Space Authority now manages the 600 hectares of conserved land in Coyote Valley and is working on a plan to partly restore the area’s historical ecology and hydrology. The authority’s natural resources manager, Aaron Hébert, says the agency is considering several restoration options. “All of them generally attempt to route some storm-flows from Fisher Creek into an expanded wetland complex in Laguna Seca,” he says, so not all of it pours into the city during peak flows. This would involve removing or notching the Cisco Systems dam to allow water to flow to Laguna Seca once again, says Clemons.

San Jose purchased the land in Coyote Valley “for the purpose of mitigating downstream flooding”, says Hébert. “Not developing the land is obviously a huge benefit for avoiding run-off and storm-water issues.” But breaching the dam so more water can reach the Laguna Seca floodplain “will also help downstream issues, fulfilling the city’s intent”, he adds.

Structures resembling the dams of beavers are built to slow the water in Coyote Valley.Credit: Open Space Authority

The Open Space Authority has started other work, such as altering an agricultural drainage ditch by installing two structures that resemble the dams built by beavers. Made of sticks and mud, the structures are inherently temporary, but they can nevertheless jump-start more-complex hydrology by slowing the flow of water, collecting sediment and allowing vegetation to sprout, which slows the flow further. It is “low-cost and simple”, Clemons says. The aim is to back-up surface water after storms and keep it from flowing quickly into the river. Individually, such projects create more wetland habitat for wildlife. If replicated throughout the region, they “could potentially have a significant [beneficial] effect on flooding, too”, Clemons adds.

A place for concrete

Even so, San Jose needs more than the restored natural hydrology of Coyote Valley to protect it from flooding, say representatives of the local utility company, Valley Water. Jack Xu, a senior engineer at the company, which manages surface water in the area, says that although projects in Coyote Valley offer “a little bit of benefit”, the valley makes up only a small percentage of Coyote Creek’s watershed. Most of it flows from the valley’s eastern foothills and is usually captured by a reservoir operated by Valley Water.

Hébert acknowledges the relative sizes of the watershed areas, but maintains that the Open Space Authority’s projects are still important. “Flooding is a cumulative impact, and every little bit you can do helps,” he says. “Sometimes just 1 foot less of water is the difference between damage and not.”

Valley Water has responded to the 2017 disaster by instituting some conventional forms of flood control. It is working on more than 7,600 metres of flood walls and other barriers along 14 kilometres of the creek; these are expected to cost $359 million, plus the cost of maintenance. From a financial perspective, Xu says, it would be better to give the creek more room. “We don’t have to maintain anything,” he says. “It would save everyone a lot of headache.” But Valley Water does not think this is an option in San Jose, because “there’s absolutely no room to widen the creek”, Xu says. However, the company did acquire 13 homes for the project.

If space can be made for water in and around cities, the benefits can be greater than simply reducing urban flooding. Such projects also protect against drought by moving water underground to feed local creeks, wetlands and rivers in the dry season. Recharging water underground also counteracts subsidence, the sinking that cities experience when they pump out too much groundwater. And de-paving helps protect against fires, because well-hydrated plants are less likely to burn.

Persuading city planners and utility companies to consider such benefits when making decisions can be difficult, because most cost–benefit analyses tend to focus on only one thing, such as how much a levee will reduce the flood risk for the neighbourhood directly behind it. Even when land-use planners understand the benefits, they can run into roadblocks if other government bodies in their watershed are reluctant to collaborate.

But nature’s jurisdictions are inviolable. “Water doesn’t obey city-limit signs,” said Graffin. “It obeys watersheds.”