The Mjøstårnet in Brumunddal, Norway, was once the world’s tallest wooden skyscraper. Credit: Erik Johansen/NTB scanpix/Alamy

When the first skyscraper was built in Chicago in 1885 — a modest ten storeys — people were afraid to walk under the steel-framed building, fearing it would collapse. Today, as towers made of wood go up in cities around the world, the response is a similar mixture of wonder and fear.

People are concerned about the fire risk and the structural stability, but the truth is that wooden construction is healthier, both for people and for the planet. Buildings and construction are the largest source of anthropogenic greenhouse gases, responsible for nearly 40% of global emissions.

Nature Outlook: Cities

A building’s structural elements, typically steel and concrete, are “a huge component of that carbon footprint”, says Michael Green, architect and author of the 2017 book The Case for Tall Wood Buildings. “That means the most important thing we can do is change the materials we build with.”

Green’s firm, MGA, based in Vancouver, Canada, is designing what will be the world’s tallest wooden skyscraper: a 55-storey tower, the Marcus Center in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. It will take the title from Milwaukee’s 25-storey Ascent tower, which in turn outstripped the 18-storey Mjøstårnet in Brumunddal, Norway. Other wooden towers are springing up in Perth and Melbourne, Australia, as wooden skyscrapers around the world reach ever greater heights.

Spectacular though they might be, timber skyscrapers are not where a shift to wooden construction will have the greatest impact. The main gains will be found in the more numerous mid-rise buildings that make up a sizeable proportion of the world’s cities. But towers and other prestige projects offer an excellent opportunity to push the technology forward and demonstrate that wood can be just as safe as concrete and steel.

“To be honest, I’m not a fan of tall buildings,” Green says. “But I am a fan of reshaping the public’s perception of possibility.”

Urban carbon capture

People have been building with wood for millennia, and many low-rise residential buildings in North America and parts of northern Europe are made from it. But its use in mid-rise buildings, towers and other large structures was limited until the advent of engineered wood technologies, such as cross-laminated timber, in which several layers of wood are bonded at alternating right angles to improve the strength.

The result is fire-resistant timber that is strong enough to be used as the main structural component of large buildings; this is what specialists mean when they talk about ‘wooden construction’. Some components, such as lifts and heating, ventilation and air-conditioning systems, are still made of other materials, and the balance between structural wood and other infrastructural materials is partly why mid-rise buildings are an appealing target for wooden construction.

MGA, which works only in wood, calculated that building a 20-storey structure from wood instead of concrete would result in a net reduction of about 4,300 tonnes of carbon emissions, which is equivalent to the annual emissions of about 900 cars. Roughly one-quarter of that gain comes from avoiding the emissions produced during the energy-intensive production of concrete. The remaining three-quarters comes from carbon captured in the wood during the trees’ life, which is sequestered when the wood is used for construction, instead of being released back into the atmosphere when the wood is burnt or decays.

The smaller carbon footprint becomes even more obvious when the calculations are scaled up. In a 2020 study, researchers at Aalto University in Espoo, Finland, calculated that if 80% of the buildings constructed in Europe over the next 20 years were made of wood, that would sequester carbon equivalent to up to 50% of the emissions of the European cement industry (A. Amiri et al. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 094076; 2020). As well as sequestering carbon directly, wooden buildings also result in fewer emissions during construction and over their entire life cycle — about 25% less than non-wooden buildings, according to another study by the same group (A. Amiri and S. Junnila Environ. Res. Infrastruct. Sustain. 5, 025012; 2025).

Unlike concrete, which needs about 30 days to cure, wood provides structural support as soon as it is in place. Combined with the use of prefabricated wooden floors or walls, this can reduce construction times by 25% , which also lowers both emissions and cost.

In some cases, using wood could reduce the cost of materials, too, depending on the supply chains and building design. “It’s different in different countries and different building topologies,” says Ali Amiri, a postdoc at Aalto University, who led the emissions studies.

Green points out that these direct expenditures are only part of what he calls the “true cost of construction”. The other costs, such as noise pollution, are borne by society and often go unacknowledged, he explains. Building with wood, which Green says is quieter as well as quicker, might reduce these impacts, too.

Industry framework

Seppo Junnila, who worked on the emissions studies with Amiri, sees wooden construction as “a long-term solution to the climate challenge”. But realizing that potential will require changes in the construction industry, which is mostly unfamiliar with using wood in mid- and high-rise construction and is slow to innovate.

One problem is that the profit margins in the industry are quite small, so companies tend to stick to what they’ve done in the past, says Pierre Blanchet, who studies sustainable buildings at Laval University in Quebec, Canada. Combined with a lack of industry standards for working with wood, this means that techniques developed for one project are seldom reused on others, slowing down the adoption of wooden construction.

The adoption of a ‘wood first’ policy in British Columbia will boost the local timber industry.Credit: James MacDonald/Bloomberg via Getty

Governments could help to resolve these challenges. “We have regulations for fire performance and structural performance and acoustic performance,” says Blanchet, and there should also be strong regulations for the environmental impact of buildings, “especially the carbon impact”, he adds.

Regulations could be implemented slowly, Blanchet explains, starting with a requirement to report the carbon impact of new constructions, then putting a limit on it, and finally decreasing the limit. Such an approach “wouldn’t just promote bio-based materials” such as wood, he says. “It would also push the steel and concrete industries to decrease their environmental impact.”

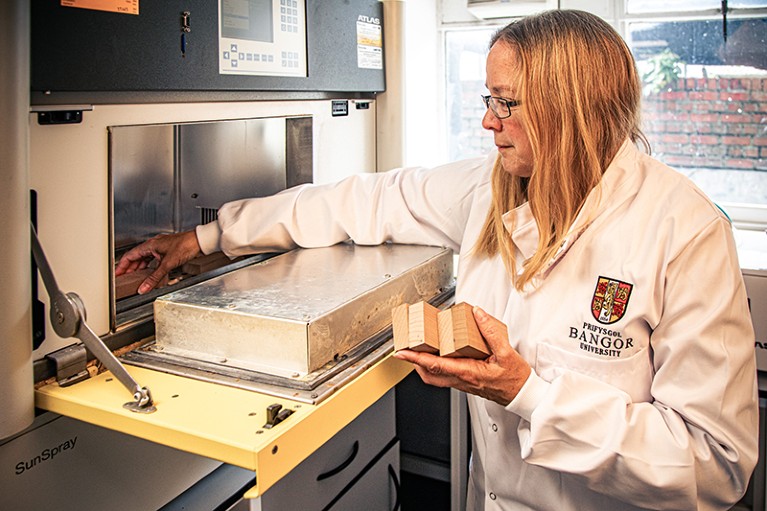

Governments also have the power to create market demand, and this would provide a reliable basis for the industry to develop the skills, standards and supply chains that are needed to support widespread wooden construction. Morwenna Spear, who studies wood modification at Bangor University, UK, authored a report with her colleagues that advised the Welsh government about the policy levers that are needed to promote an increase in wooden construction. “One of those would be to influence procurement to encourage people to use wood in buildings they’re directly financing, such as new public buildings,” Spear says. “That would stimulate the forest products’ value chain, sawmills and the wood industry.”

Morwenna Spear assesses the effects of UV light and rainfall on wood samples in an accelerated weathering chamber.Credit: Bangor University

This is already happening in parts of Canada. Anne Koven, a co-founder of the Mass Timber Institute at the University of Toronto, explains that provincial governments in Quebec and British Columbia have already instituted wood-first policies: contractors for public buildings are required to justify their decisions to use materials other than wood.

“I think that’s fantastic, because both of those provinces are economically dependent on the forestry industry,” she says. But it is important, she adds, that the financial benefits of building with wood are shared with those most affected by forestry. In Canada, this is often Indigenous people living in rural areas. “We have to think about how to push some of the economic benefits of wood further down the supply chain, back into those remote communities,” she says.

The many lives of wood

Much of Spear’s research focuses on extending the lifespan of wooden structural elements. The carbon sequestered in wooden buildings remains captured only as long as the wood is intact. If the wood is discarded and decays, or is burnt, the carbon will be released. From a climate perspective, it is therefore important to keep wooden elements in use for as long as possible, and this might include reusing or recycling them.

At the end of a building’s life, the fate of the timber elements depends on their condition. Ideally, large structural elements such as beams will have enough remaining integrity when taken down to be reused in another building as they are. “It’s best to keep it solid for as long as possible,” Spear says. Parts that are in worse shape can instead be chipped down to make particle boards, but this is a one-way street. Spear recommends combining wood particles of roughly the same size to increase the likelihood that the board can be reworked again.

The College of Forestry at Oregon State University has two buildings made from wood.Credit: Josh Partee/Michael Green Architecture

Spear is developing models to estimate the total life of wood that is reused and processed into different products. “You’ve got the lifespan of each product, and then you can add them up through the chain,” she says. “You can work out the net effect for taking a log from the forest and going through some notional sequences of lives, and model how long that carbon resides and how much of it exits the system.”

Understanding the material flows through cycles of reuse and reprocessing is important, not only to estimate how long carbon remains sequestered, but also to understand how incentives and other policy choices could affect the retention time. “The best and most effective thing we can aim to be doing is connecting the timber that comes out of a building with a second life in its solid state,” says Spear. This requires the creation of networks and markets “to connect the people who’ve got that material with people who’d like to do a project with it, to use it in its best state.”

No room for purists

Blanchet echoes this sentiment, but says that considerable work is needed to achieve it. “The holy grail is to be able to reuse it at the end of life. For concrete, that’s impossible,” he says, but it’s not straightforward for wood either. Many wooden elements will be contaminated by other materials, he explains. They might contain screws, for example, or they might be glued to other materials, or even coated with concrete for acoustic performance. This makes reuse more difficult. “Theoretically, it looks feasible. In practice, it’s not exactly the case,” Blanchet says. “From my point of view, there’s still a lot of work to do.”

Complexities such as these are why Blanchet thinks that wood will not always be the best or only way to build sustainably. “I strongly believe in wood’s environmental impact, I strongly believe in improving its durability, and I strongly believe in not using wood where it underperforms,” he says. “Using all materials in their proper place could lead to better, longer-life buildings and benefit society.”

Green, too, is cautious about people becoming purists over wood. “There’s a crossover point where you’re throwing so much wood at a problem, that arguably it would take less carbon to use steel,” he says. “People ask me whether I could build a large building like a stadium from wood. The answer is absolutely, you can. But you want to do the analysis of whether you should.”

More than a decade ago, Green was an early advocate of wooden construction. Since then, he has continued to think about improving the construction industry’s climate impact. His question now is what new structural material could replace the big four widely used in construction: wood, steel, concrete and masonry. One possibility, which he favours, would be creating a material from plant fibres that can be formed into organic, efficient shapes, minimizing waste and capturing carbon at the same time. “Wood is a fantastic solution,” he says, “but it’s not the best solution, not the forever solution. The best solution is something we don’t yet know about.”