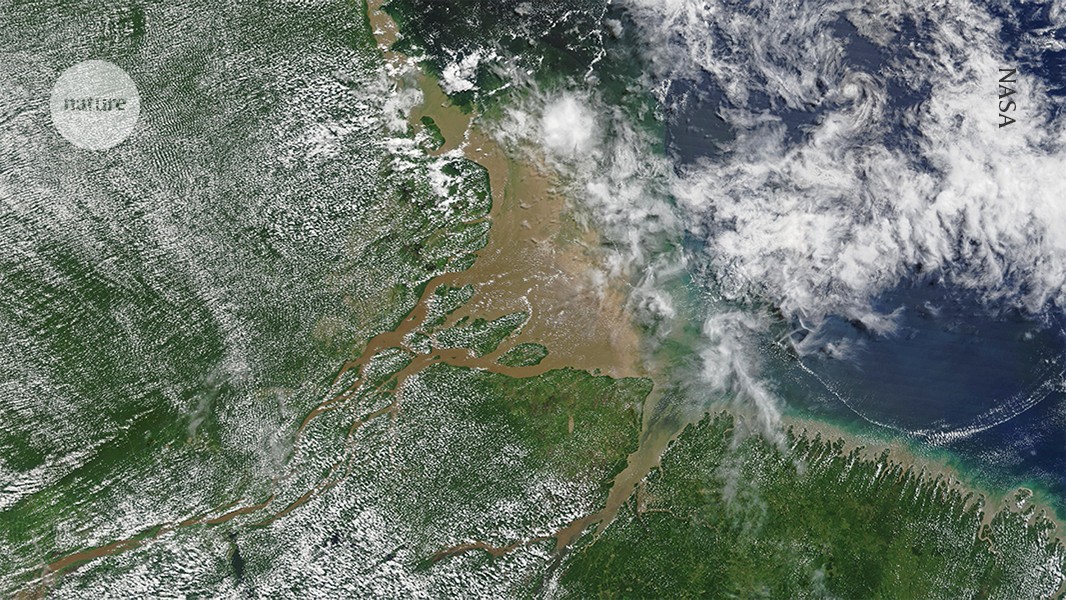

A tropical forest meets the Atlantic Ocean at the Amazon Delta.Credit: NASA/Alamy

As the world gathered in Belém, Brazil, for the COP30 United Nations climate conference, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva reignited an old but urgent debate: whether the multilateral process that has sustained climate diplomacy for three decades is still fit for purpose. His proposal for a global climate council — a smaller, more agile entity to lead negotiations and ensure that climate commitments are implemented — reflects mounting frustration with the slow pace of outcomes from the annual Conference of the Parties (COP).

How to fight climate change without the US: a guide to global action

Lula’s proposal deserves serious consideration. The COP process has become sprawling, performative and, at times, politically paralysed. Yet, as someone who helped to draft the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1991–92, I think that the answer is not to abandon this architecture, but to reform it.

When we negotiated the UNFCCC, our goal was to create a durable legal scaffold that was flexible enough to evolve with scientific understanding and national capacities for climate action. In 1992, there was no precedent for a framework that addressed an issue that spanned every economy, ecosystem and generation of people. We had the science, but not yet the institutions or political will to act at scale. The framework-convention model allowed successive protocols, decisions and mechanisms to develop.

That design has proven remarkably resilient. If someone had told me in 1992 that the world would still be negotiating climate action at COP30, I might have sighed. Yet, if they had told me that every nation would still be adhering to the same framework, guided by science and law, I would have been profoundly hopeful — as I am today.

Climate diplomacy is slow because it is systemic. It forces nations to reconcile competing imperatives — development versus decarbonization, growth versus justice, and responsibility versus capability. The principle of common but differentiated responsibilities was born from these tensions: recognition that all countries share the problem but not the same level of blame or means to act.

‘Almost utopian’: how protecting the environment is boosting the economy in Brazil

Progress has been incremental but cumulative. The UNFCCC, Kyoto Protocol and Paris agreement have created a coherent legal architecture for climate governance. The International Court of Justice delivered an advisory opinion in July, reaffirming that states have binding obligations to protect the climate, an indication of how far we’ve come.

Criticism of the COP process is understandable. Yearly gatherings of tens of thousands of people can seem detached from the crisis outside the conference halls. But dismissing COPs ignores their ability to provide universality, legitimacy and accountability. President Lula’s call for a leaner climate council acknowledges this frustration while maintaining the inclusivity of the COP process.