As part of her work on the Inuksiutit project, Jessica Penney travelled to Mittimatalik, a community in the northern part of Baffin Island in Nunavut, Canada.Credit: Peter Loovers

As a sociologist and an Inuk who was raised in Canada’s northernmost city — Iqaluit in the territory of Nunavut — Jessica Penney has spent much of her professional career studying the country’s Inuit communities. During this time, she has seen growing threats to the food security, cultural practices and mental health of the Inuit and other northern Indigenous peoples.

Inspired by her community connection with the people of Nunavut, Penney studies Inuit health, environmental issues and food sovereignty — the right of Indigenous communities to control their own food sources and access — from her current base at Toronto Metropolitan University. She is also a co-investigator on the Inuksiutit Project, an initiative by the University of Aberdeen, UK, and York University in Toronto to promote local control of food in Nunavut.

Penney shares with Nature her research journey.

Tell us about your path from Iqaluit to a career in academia.

Iqaluit may seem small and remote, but with just over 8,000 people, it’s a large town by Inuit standards, and it’s the cultural hub of Nunavut. All of the issues I study as a sociologist — food sovereignty, poverty and the resonance of native traditions — are Nunavut issues.

Nature Spotlight: Canada

The educational system in Nunavut has some challenges. There’s a serious lack of Inuit teachers and resources. For the last two years of secondary school, I attended an international school on Vancouver Island on a full scholarship. After being exposed to so many cultures, I wanted to attend university abroad and I applied to universities all over the United Kingdom. The University of Glasgow offered me a scholarship in my preferred field of sociology and public policy, so the choice was easy.

I stayed at the University of Glasgow for my master’s and PhD degrees, although I never lost my focus on the Indigenous peoples of northern Canada. Every summer, I would go back to Nunavut to work for the health-policy department, so I was able to link up my studies with my actual work. I did my master’s in global health, and that also helped me start to see some of the connections between health and social issues in my community, as well as links to environmental issues, especially those relating to climate change.

My PhD thesis explored the social, political and economic disruptions caused by the Muskrat Falls hydroelectric project, which dammed the Churchill River in the eastern province of Newfoundland and Labrador and was completed in 2021 at a cost of roughly Can$13 billion (US$9.3 billion). I interviewed local Inuit to document their concerns about the project and its anticipated environmental impacts. The dams changed the lives of locals, including their ability to hunt and fish, and many felt powerless and voiceless as construction went ahead.

Why is food sovereignty and security such a pressing issue in Nunavut?

Wherever they live, people should always have some control over their food supply. But control is slipping away in Nunavut. Most food has to be shipped from the south, and the few grocery shops in Nunavut are incredibly expensive — with some items priced at two to three times the national average — and stock limited supplies that are often of poor quality. In Nunavut, a family-sized box of cereal can cost nearly Can$18.

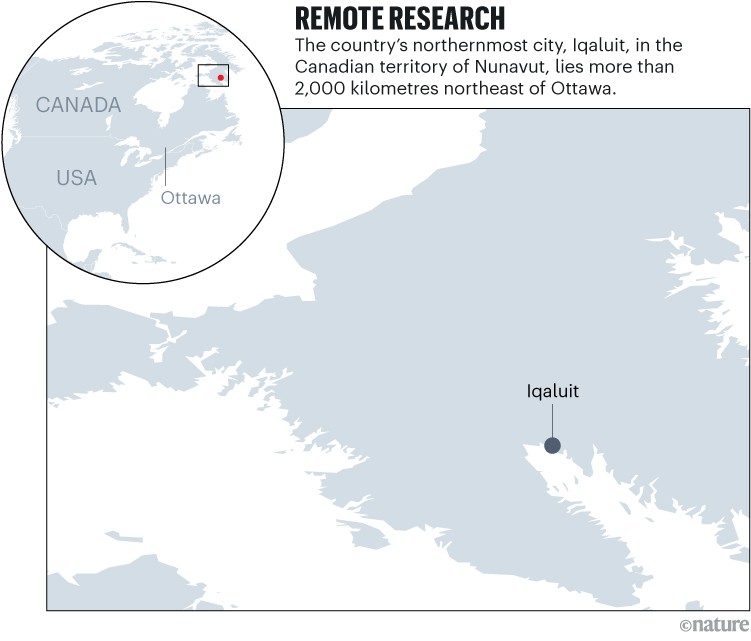

Traditional methods for harvesting food are also under threat. The sea ice around my hometown of Iqaluit (see ‘Remote research’) and many other northern communities is less stable and dependable than it was a few decades ago, which means that local hunters have a harder time finding and reaching ringed seals (Pusa hispida), a major part of the traditional diet, clothing and culture. Inuit eat seal meat, blubber and organs. They still turn seal skins into trousers and parkas. Hunting, sharing and using seal products is a focus of community bonding and Inuit identity.

Climate change isn’t the only challenge. The Canadian government has been considering listing ringed seals as a species of concern, a designation that could greatly limit hunting. As part of this effort, the government surveyed people in Nunavut. As noted by my Inuksiutit Project colleagues, the questionnaire was available only in English and French, which greatly limited input from Inuktut-speaking people who have some of the deepest knowledge of seal populations and have the most at stake. The survey was also conducted online, which limited input from elders and those without iInternet access.

In February, I co-authored a piece in The Conversation that documented the ongoing food security crisis faced by Inuit children in Nunavut. Canada’s 2022 Indigenous Peoples Survey found that 80% of Indigenous children in the territory live in households experiencing food insecurity. In that article, my co-authors and I advocated for the renewal of a federal voucher programme that provides Can$500 per child each month for groceries, and another Can$250 for children under four for formula milk and nappies. The programme had been at risk of expiring, which could have been catastrophic.