When Calvin Santiago Lee decided to look beyond his home in the United States for a PhD position, finances played a decisive part. “I believed that unless I got extremely lucky in the US, there would be little chance of being financially stable during my PhD and having good career prospects thereafter,” says the theoretical computer scientist.

The global PhD landscape 2025

His current position working on category theory — a mathematical field related to programming languages and logic — at Reykjavik University in Iceland pays well and provides good work–life balance. “I feel like a valued member of society and can live a comfortable life while pursuing a PhD. I believe that even at top US institutions, this would not be a guarantee.”

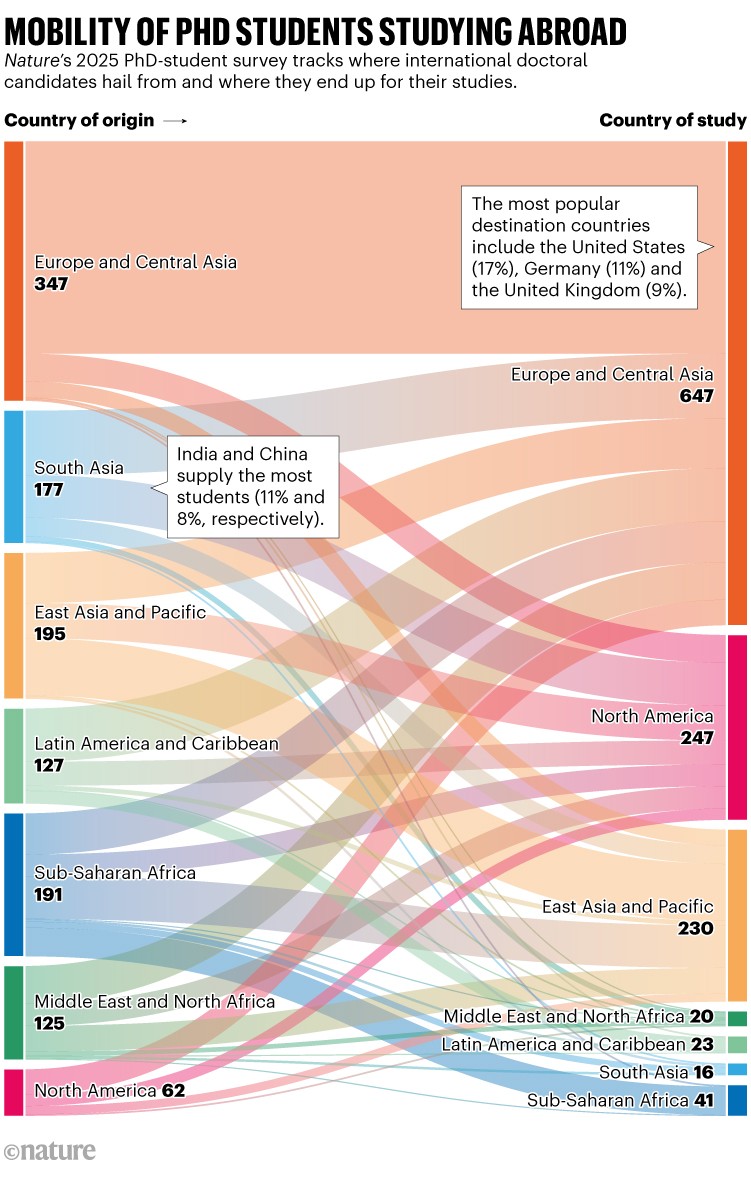

Lee’s move captures a sentiment shared by many young researchers. When Nature surveyed nearly 3,800 PhD students worldwide in May and June, about one-third were based outside their country of origin (see ‘Mobility of PhD students studying abroad’). Among the 1,232 respondents studying abroad, the most common reason for their move — cited by 43% — was “a lack of funding at home”.

That proportion is on a par with Nature’s two previous PhD surveys in 2019 and 2022, when around 45% of those earning a PhD abroad said finances had played a key part in their move. However, in both of those surveys, it was not the top reason. Instead, that was “to experience another culture”, chosen by roughly half of respondents (49% in 2022 and 46% in 2019). But this year, only 35% selected that option. (Note that some options have changed from previous surveys, which might have influenced respondents’ selections.)

Other motivations for studying abroad that have seen a drop include “more job opportunities post-study” (from 42% in 2019 to 35% in 2025) and “a lack of, or low quality, programmes at home” (40% in 2019 to 28% in 2025). Altogether, this suggests that students are making more-pragmatic decisions, guided by financial and career considerations rather than by personal exploration.

The numbers make sense, says Chris Glass at Boston College in Massachusetts, who researches trends in higher education. He says that shifting visa rules, uncertain post-study work permissions and geopolitical turbulence have “changed the calculus” for prospective PhD students globally. “International doctoral talent today demands tangible economic and scientific returns — not just the promise of experiencing another culture,” he adds.

Glass says that students are increasingly asking: “Will I be able to stay and build a research career? Are my skills marketable in the host country — and globally?” He thinks that it’s both an adaptive response to policy headwinds and a sign that students are optimizing their choices for impact and opportunity in a world in which “uncertainty is the norm”.

Political push

Politics is a minor motivation for moving abroad. Overall, just 7% of respondents say that political reasons influenced their decision, a share that has changed little since Nature asked the question in 2017.

How money, politics and technology are redefining the PhD experience

But among some nationalities, notably Russians and Americans, the proportion is higher. More than half (56%) of the 16 respondents from Russia studying abroad cited politics as a factor, as did nearly one-quarter (24%) of 46 students from the United States. By comparison, just 4% of respondents from India and 7% of those from China who were studying abroad said the same.

US students living and studying abroad said that repressive politics and the current presidential administration’s attitudes towards science and research were key reasons for their choice. Asked to elaborate on her reason for leaving, one woman studying in Switzerland simply wrote: “Trump…”

Tensions at home are also thwarting US students’ desire to move back after their PhDs. “I had planned to strongly consider returning to the United States but now those plans are, at a minimum, on hold,” says one in Australia, who requested anonymity out of fear of career repercussions. He says he has “little interest in returning to what amounts to a totalitarian regime” where people like him — a Jewish liberal in a polyamorous relationship — are “effectively targeted for maltreatment, harassment and potentially worse”.

He says that most of his friends who are early-career researchers back in the United States either have escape plans or are developing them. Australia is great, he says, because it’s more tolerant than the United States, and the physical infrastructure of roads and buildings “isn’t crumbling, like at home”. It’s also much safer. He used to keep his ‘stop the bleed’ kit clipped to his bag for instant access in case of a mass shooting. “Now, it’s just tucked in the bottom of my backpack.”

Russian PhD student Daniil Kiselev studies in France, where he connects with the culture, including this eighteenth-century self-portrait of French painter Joseph Ducreux.Credit: Daniil Kiselev

Daniil Kiselev, a PhD student originally from Russia, now at the University of Montpellier in France, left his home country in 2021. At the time, Russia had occupied Crimea, but the full-blown invasion of Ukraine had yet to happen. “Back then, options remained relatively rich. The path to work abroad was demanding, but straight and offered some visibility,” he says.