Just in May of this year, the Soviets struck a ground target from orbit. Never mind that they didn’t intend to; in fact, never mind that there are no ‘Soviets’ anymore. A piece of Cosmos 482, a rocket intended for Venus that broke up during launch way back in 1972, finally came back home after a 50-year road trip circumnavigating the Earth. Where did it crash? Uh… no one really knows, actually. Maybe near Indonesia. This thing weighed half a ton and wasn’t moving slowly as it fell back to Earth. It didn’t hit a populated area, but it easily could have. And as near-space gets more and more congested, the odds of a catastrophe like that are only getting bigger.

A recent science article in npj Space Exploration lays out the growing risk, and it’s not exactly a comforting read. There’s no real agreed upon framework for which country (or now, company) can put how many objects into orbit; there’s not even a formal way to coordinate space traffic to prevent accidents. The U.S. was building out such a service, the Traffic Coordination System for Space, but that’s on the chopping block in the Trump administration’s proposed budget cuts. Other than that, the U.S. Space Force can track space objects, notify satellite operators of an impending collision, and then just hope that the operator does something about it. And… that’s it, really.

One could argue that this has been an unacceptable problem since the dawn of the space age, and I wouldn’t disagree. As astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell recently told EarthSky, meteor-size space debris have been crashing down to Earth with regularity for the past 60 years. Most of these are uncontrolled, uncoordinated, and even untracked descents. The reason none of them have hit populated areas is because of luck. Yes, luck. Sleep well tonight! The only saving grace was that these crashes were relatively infrequent, because there just wasn’t that much stuff up in space. That last part is changing fast, and that’s making the Earth a more dangerous place to live.

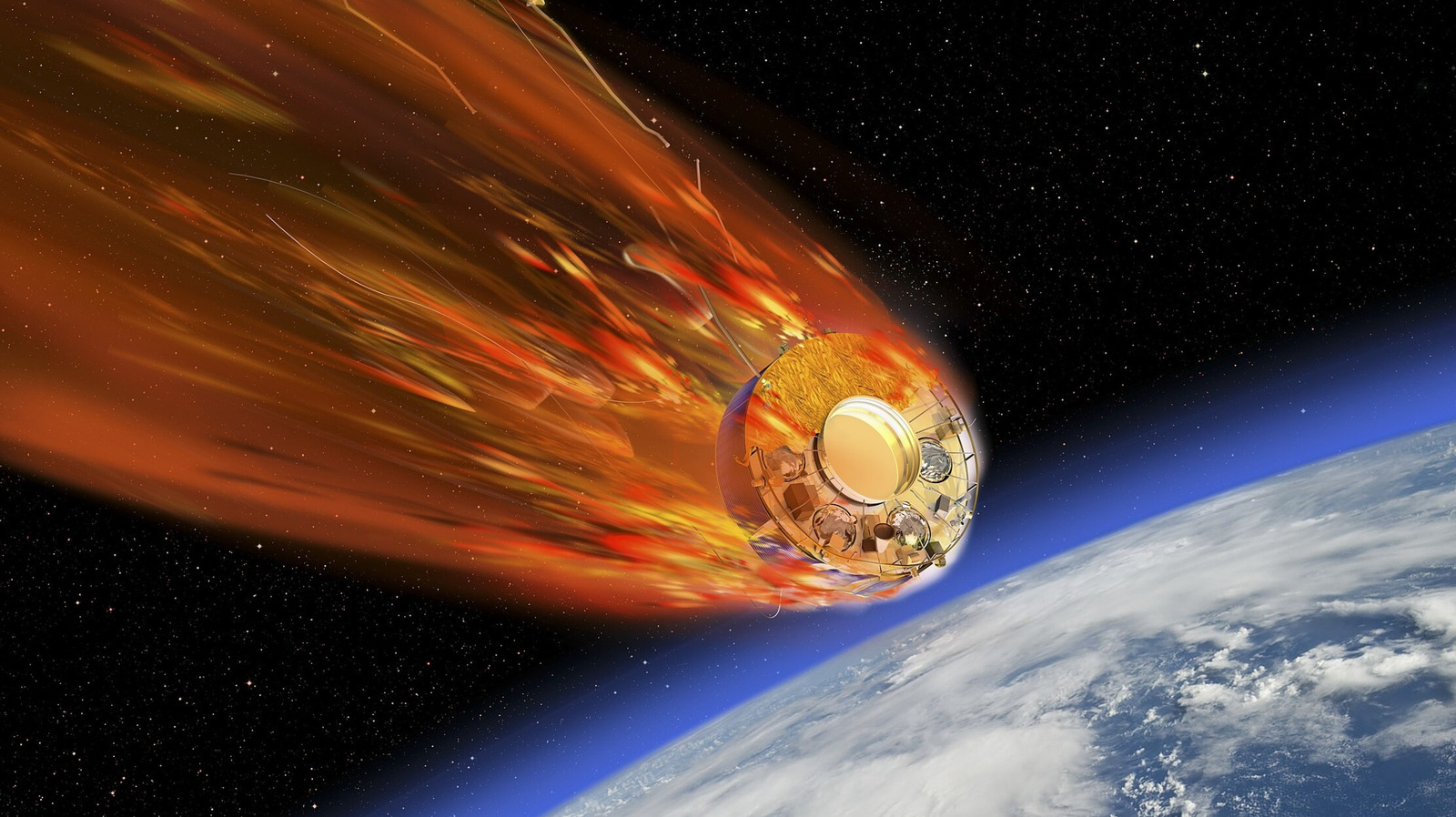

The blazing death of LEO satellites

Most satellites only live for around five years, after which they are often intentionally lowered to allow atmospheric drag to pull them out of orbit. That way, they don’t stay in low earth orbit (LEO) for long periods as space junk. But what about those satellites that die before they can be repositioned, or that were never designed for that in the first place? Well, it turns out that even LEO has trace amounts of atmosphere, causing just enough drag to de-orbit the satellite anyway. That’s uncontrolled, though, meaning nobody knows where the thing will come down.

Usually, the satellite burns up in atmosphere. That may cause its own problems (is vaporized metal in the atmosphere a good thing?), but at least there’s nothing left to crash. Sometimes, however, an intact chunk survives, which becomes a kinetic threat to anything beneath it. And the larger the returning object, the more likely that a heavier piece will remain solid.

Recent history isn’t great here. China, which is getting increasingly aggressive with its space plans, seems to be prioritizing speed over any kind of safety. The country put some 20-ton rockets into space, which then fell back to Earth uncontrolled; one piece hit Borneo, another fell in West Africa. Again, these avoided hitting population centers by using luck. But besides a country putting big things into space, we also need to start worrying about companies putting lots and lots of small things into space.

Orbital congestion

As this chart from the European Space Agency shows, the number of objects being put into LEO has skyrocketed in the last five years. This is almost entirely down to SpaceX, which in turn is almost entirely down to its Starlink constellation. The service currently operates over 8,000 orbiting satellites, and its ambitions are to get somewhere around 42,000 up there eventually. Meanwhile, competing companies like Amazon are beginning to put their own constellations into LEO; also meanwhile, China has two of its own constellations that it wants to start spinning up.

If even half of all these proposed satellites get up there, that is a huge increase in the total number of objects in LEO (there’s currently only 20,000 tracked objects total). As it stands, Starlink satellites do tens of thousands of maneuvers, every single year, just to avoid hitting stuff. Get even one of those maneuvers wrong, and that’s potentially a crash. The odds of that go up exponentially for every new satellite, and, well, there’s a lot of new satellites coming.

Whose fault is any of this?

I know all of this may sound scary, but rest assured: the actual treaties governing this stuff are decades out of date. As the npj Space Exploration article says:

The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 holds launching states responsible for any harm caused by their space activities, whether from debris, malfunctioning satellites, or uncontrolled reentry. The Liability Convention of 1972 further specifies that any damage to another country by space objects requires compensation from the responsible state.

Great! So, uh, where would Indonesia go to get their recompense from that Soviet crash? Even if you could argue that the modern Russian state should pay it, good luck making that happen. And even if you could do that, payment doesn’t seem like an answer to a half-ton object potentially hitting a city center. There’s no real precedent for what happens in that case, and again, there’s no framework for space traffic management or de-orbiting.

In the meantime, crashes are only going to get more frequent, and it’s only a matter of time before a major incident (or near-incident) occurs. Hopefully, this new space age we’re in will incentivize governments to preemptively work out some new treaties or agreements. Until then, watch out for Soviets. From space.