You have full access to this article via your institution.

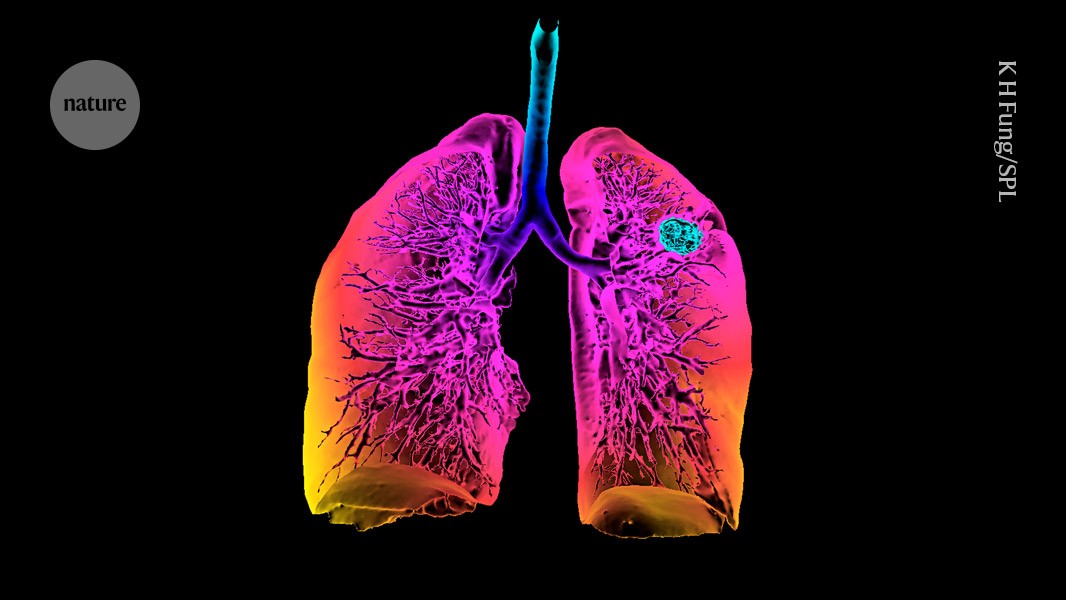

Nature’s modelling shows that previously awarded NIH grants that could be at risk today include funding for a project investigating whether computed-tomography scans improve detection of lung cancer. Credit: K H Fung/Science Photo Library

In 2011, researchers discovered that, compared with radiography (X-rays), computed tomography (CT) scans improved detection of lung cancer, reducing deaths by one-fifth (The National Lung Screening Trial Research Team N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 395–409; 2011).

Their study, which has been cited almost 10,000 times, was made possible by a US$57-million National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant that funded a research institute at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Without that grant, “we would not be able to identify what is still today the largest single way of reducing deaths from lung cancer”, says lead author Denise Aberle, a radiology researcher at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine.

What research might be lost after the NIH’s cuts? Nature trained a bot to find out

Yet if the team was seeking grant funding now, the work might not have happened. That’s the conclusion of an analysis by reporters and data scientists in the Nature Careers and Nature Index teams. They trained a machine-learning model on existing NIH grants that have been cancelled since Donald Trump began his second presidential term and applied it to previously awarded NIH grants, to see which ones would have been at risk of cancellation. The grant that funded the lung-cancer-screening study was among those at risk.

Some 5,000 grants worth around $4.5 billion have been frozen or cancelled so far, as Nature’s news team has reported. Despite ongoing lawsuits, efforts to reinstate the cut funding remain an uphill battle. It is, of course, the US government’s prerogative to decide its spending priorities, including directing funding towards some broad areas of science and away from others. But the fact that a credible simulation of the administration’s current policies found that life-saving work, with huge societal and economic benefits, might have been cancelled shows the self-defeating folly of how those policies have been implemented — and the need for an urgent change of approach.

As of now, the NIH has not published any methodology or criteria for cancellation, and it has not announced how these decisions are being made. The agency has not replied to several requests from Nature to explain its methods. But we do know some things.

Exclusive: NIH to dismiss dozens of grant reviewers to align with Trump priorities

We know, for example, that NIH grant reviewers are being replaced with people whose stated views are more aligned with the administration’s priorities. And in March, The New York Times scanned US government websites and found directives to remove 200 words and phrases, among them ‘equitable’, ‘pregnant people’ and ‘systemic’ — such as in systemic racism — in line with executive orders issued by the White House.

In June, the investigative-journalism organization ProPublica spoke to a whistle-blower who explained how he used artificial intelligence to identify candidate grants for cancellation at the Department of Veterans Affairs. Independent researchers we have spoken to say that the NIH might have used this approach.

The Nature analysis used data from two sources to train its model: the NIH’s database of publicly accessible grants, called RePORTER, and Grant Witness, a website that tracks cancelled grants.

The results are eye-popping. More than 1,000 grants, worth almost $5 billion, had a 60% or higher likelihood of cancellation. The research funded by these grants resulted in 50,000 papers, which together have attracted three million citations. The work likely to have been cancelled is not only in fields targeted by the Trump administration, such as transgender health or diversity, equity and inclusion programmes. In the model and at the NIH, they run the full gamut of science: from public-health programmes to basic research into genetics, immunology and cancer.

Destructive decisions

However the cancellations were decided on, the impact on science and on scientific careers will be huge. We will certainly never know what research — and public benefit — might have come from the billions of dollars of science that have now been lost.

Judge rules against NIH grant cuts — and calls them discriminatory

But hammering through vast swathes of publicly funded research without consulting the people doing that science, without a clear rationale for decisions, methodology or technique, isn’t in the interests of science, the US taxpayer or, indeed, the world at large. It is inexplicable and destructive. At the very least, decisions on individual grants should still be peer reviewed by specialists in the relevant field.

For many researchers in the United States, a practical response to the current situation might well be to attempt to adjust, to tick the right boxes, to avoid any words that might upset an algorithm and to hope that reason soon prevails again. But there is still a risk that this approach to funding science will become both normal — and contagious. For governments in other countries, the United States, as the world’s pre-eminent science power, is showing that it is normal to interfere with grant-assessment panels. At that point, the integrity of science might well be gone for good.

That hasn’t happened yet. But now we can see just how much is at risk. The US government — and governments elsewhere tempted to go down a similar route — should take note.