When US President Donald Trump’s administration started slashing science funding in January, Nicole Maphis wasn’t especially worried about her research being affected. She studies the fundamental biology of Alzheimer’s disease, which didn’t strike her as a probable target.

The change in leadership came at a pivotal time for Maphis: she was finishing her postdoctoral studies at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque, and seeking a highly competitive grant from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). The grant aims to increase diversity in life sciences, and Maphis was eligible as a woman from a family with a low income. The funding, she hoped, would launch her into an independent role as a professor.

The trouble started in February. First, the funding opportunity to which she had applied disappeared. Then, a staff member at the NIH informed her that her proposal had been pulled from consideration. “I’ve never cried more as a scientist than in the last six months. To hear the NIH staff member say, ‘I’m so sorry but your application has been moved’, to what is essentially the trash, makes it seem that everything you’re doing is worthless,” Maphis says.

US Supreme Court allows NIH to cut $2 billion in research grant

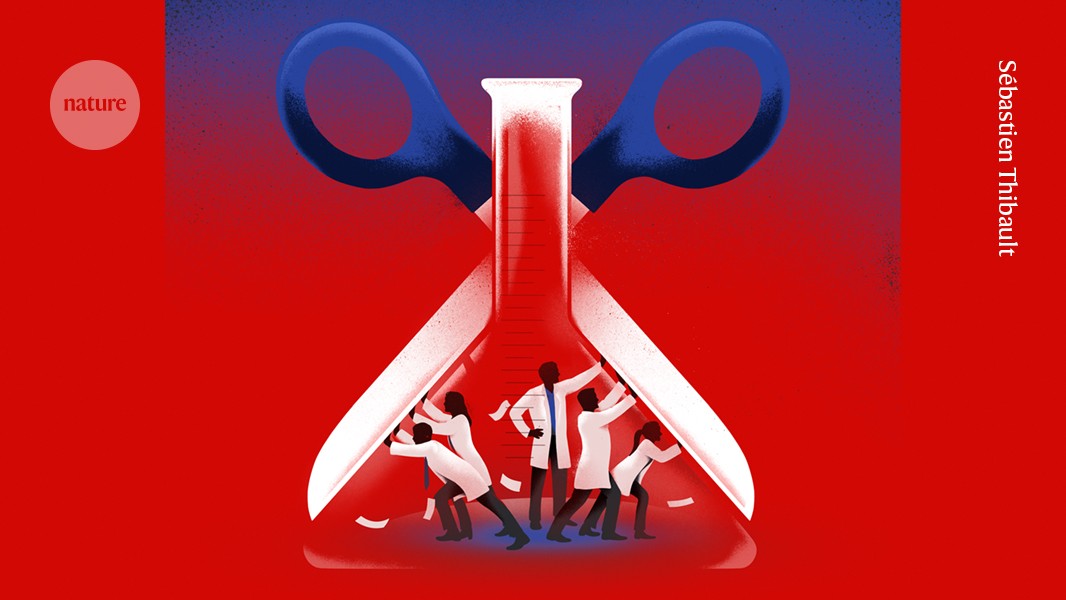

She had become ensnared in Trump’s war on anything with a connection to diversity, equity and inclusion. Maphis has been joined by thousands of other scientists who have been forced to halt their work as the administration continues to purge funding for science that doesn’t align with its ideological road map. This includes research on climate change, COVID-19, RNA vaccines, the spread of misinformation and the health of women and people from sexual and gender minorities (LGBTQ+).

But Maphis and other scientists are fighting back against the administration. Some, like her, are suing to reinstate grants. Some are collecting information about the budgetary carnage to keep a record of the administration’s actions and to help in lawsuits. Others are trying to spread the word about the damage that is being done, either publicly or secretly, often risking their own careers in the process.

Nature talked to several people who are leading the fight to reinstate funding, retain knowledge and protect institutions such as the NIH and the US National Science Foundation (NSF), two of the largest sources of public funding for basic research in the world. “We’ll have nothing left at the NIH if people don’t speak out about this,” says one staff member at the agency, who asked not to be named because they were not authorized to speak to the media.

Day in court

Maphis dreamt big as an undergraduate. She wanted to develop a vaccine against Alzheimer’s disease. Although it seemed far-fetched at the time, a decade later, she and her colleagues developed a candidate with promising results in mice and non-human primates. It can clear protein tangles, which are known to be linked to the disease, from the brain and it seems to improve cognitive function in the animals (N. M. Maphis et al. Alzheimers Dement. 21, e70101; 2025).

Watching her grandmother slowly succumb to the illness years ago was a big motivator for her research. “I haven’t been able to move away from it, knowing that there could be these modifiable risk factors that we’re not studying,” she says.

After her funding was put on pause, she sprang into action and joined the local chapter of Stand Up for Science, a non-profit organization that aims to combat the Trump administration’s policy and funding changes to the scientific enterprise. With this group, she led a middle-school science outreach programme for girls, wrote an opinion piece in her local newspaper and led a protest.

In March, Maphis heard word about a brewing lawsuit. She thought she had little to lose: “My career is already ruined, so I might as well do something about it,” she says. She reached out to the attorneys to explain her situation and joined the case when they filed suit in early April.

The case captured wide attention in June, when judge William Young at the US District Court for the District of Massachusetts in Boston ordered that hundreds of terminated research projects at the NIH be reinstated. He called the explanations that led to their cancellation “bereft of reasoning — virtually, in their entirety”, and he excoriated the Trump administration for what he saw as clear discrimination against racial, sexual and gender minorities. A spokesperson for the NIH’s parent agency, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), said at the time that the agency “stands by its decision to end funding for research that prioritized ideological agendas over scientific rigour and meaningful outcomes for the American people”.

Can NIH-funded research on racism and health survive Trump’s cuts?

In late August, the US Supreme Court put a key part of Young’s ruling on hold, allowing the administration to cancel up to US$2 billion in funding that had been on the chopping block.

This case will continue, along with several others by states, associations and individual scientists. In June, Nell Green Nylen, a specialist in water law and policy at the University of California (UC), Berkeley, filed a class-action lawsuit alongside several of her UC colleagues, alleging that the Trump administration has improperly cut research projects worth hundreds of millions of dollars. The fact that scientists, and not school administrators, are leading the push is meaningful, Green Nylen says. “It feels really important for us that there was something we could do as researchers to fight back and to make a difference for ourselves.”

Government scientists have been involved in these legal battles, too — behind the scenes. They have been exercising their whistle-blower rights by telling congressional officials, attorneys and reporters what is happening inside federal agencies, such as violations of long-standing policies and procedures that were put in place to maintain scientific integrity. Such concerns led one NIH programme official, who requested anonymity because they are not authorized to speak to the press, to take action.

They recall the precise day the NIH began to terminate grants: 28 February. “That was a crystallizing moment,” they say. “We all took an oath to the constitution to protect from enemies foreign or domestic — so I had to get in touch with those who had power to stop some of this.”

Data dredgers

One challenge in raising these cases against the government is that the extent of grant terminations, and the processes used to accomplish them, have been opaque. The Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), initially led by billionaire Elon Musk, was behind many of the cuts, and the chaotic way in which agencies were responding to its demands have made it difficult to track which funds the government cut and why.

Noam Ross co-founded Grant Witness to collect and collate information on cancelled funding.Credit: Shuran Huang for Nature

Noam Ross was familiar with the struggle to get information from hard-to-access government databases — what he calls “stubborn systems”. Ross, a computational ecologist and the executive director of rOpenSci, a non-profit initiative that aims to improve data accessibility in science, wondered if there was a way he could document which NIH grants were being terminated. He noticed that the few known terminations had all received modifications in an HHS system called TAGGS, short for Tracking Accountability in Government Grants System. Using these modifications as a proxy, Ross started logging terminated grants in a spreadsheet that he created with Anthony Barente, a data scientist at the pharmaceutical company Bristol Myers Squibb in Boston, Massachusetts.

In March, Scott Delaney, an environmental epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, began crowdsourcing information for a similar spreadsheet of terminated grants. “It was explicitly an effort to organize, to advocate, and then for me personally, to support litigation,” says Delaney, a former lawyer.

Later that month, Ross and Delaney joined forces to create what is now known as Grant Witness, a project to track the termination of grants. By early April, they had a spreadsheet with hundreds of grants listed. The database, and others like it, proved invaluable for reporters, activists and politicians who were trying to understand what was happening at the NIH. Weeks later, the pair expanded their efforts to include NSF grant terminations. Using data-dredging skills and crowdsourced reports, they pieced together a catalogue of cuts including detailed information about spending, down to the congressional district.

With a detailed database, it has been easier to show that the government disproportionately targeted research that could benefit women, or those from LGBTQ+ and minority ethnic groups. Judge Young mentioned the work of Grant Witness as the case against the Trump administration proceeded.

Scott Delaney tracks terminated research grants.Credit: Sophie Park for Nature

Government workers, again, have been part of the effort to track cancelled research grants. Shortly after DOGE was established at the NSF, hundreds were slated for termination. It was “scientifically meritorious work that’s being pulled back for partisan political reasons”, says one staff member at that agency. But information was limited. “It wasn’t really being tracked at all,” another NSF worker says. A spokesperson for the NSF declined to comment for this article.

Staff at the NSF banded together, looking for ways to collect data on terminated grants and make them public. Their tracking effort informed Ross and Delaney’s and helped to emphasize who was being targeted at the NSF. Although men receive around 60% of grants provided by the agency, 60% of the terminations were made to grants held by women.

About a month after the first terminations, the NSF published its own official list of cut grants. “I’m glad the NSF published the list,” says one staff member. “They should have done that to begin with.”

Getting the word out

Legal battles and data collection might not be enough if the public doesn’t care about the science that is being defunded. Many researchers noticed that the public’s perception of science was shifting well before Trump’s re-election.