You have full access to this article via your institution.

Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

Queen Iberian harvester ants (Messor ibericus) can give birth to ants of their own species (left) and, using a cloning trick, offspring of a different one (Messor structor, right).Credit: Jonathan Romiguier, Yannick Juvé, Laurent Soldati

Iberian harvester ants (Messor ibericus) rely on hardy workers that are hybrids of their own species and another one, Messor structor. But the queens don’t bother keeping any M. structor males around: they make their own. M. ibericus queens can lay eggs that contain only M. structor DNA in their nuclei. They then mate with those M. structor ants to produce the hybrid workers. In effect, M. ibericus has domesticated M. structor and its genome, says evolutionary biologist Jonathan Romiguier, who co-authoured the research.

The planet’s capacity to store carbon-dioxide emissions deep underground is much smaller than previous estimates suggest. A new estimate suggests that geologic carbon-storage space could run out as early as 2200, so we can’t rely on it too much to meet the desperate need to slow climate change. Then there’s the question of where: some of the places with the most storage potential, such as Indonesia, Brazil and some countries in Africa, could end up holding the bag for a problem they didn’t create. Russia, the United States and Canada have both the space and the money to more easily step up to the plate. But the real solution, it will not surprise you to hear, is to slash fossil-fuel emissions now, write the researchers.

A highly lethal type of brain tumour, glioblastoma, often steals key nutrients to aid its aggressive growth — a habit that can be exploited to slow the cancer’s spread. Researchers fed mice with certain kinds of glioblastoma a diet that lacked serine — a crucial amino acid — and found that the rodents’ tumours grew more slowly. The animals also lived longer.

Features & opinion

Academics looking to get into bed with big tech companies such as Alphabet, Meta or Microsoft might be tempted by vast R&D budgets, proprietary data and innovative tools. But academics might also be wary of ethical concerns and conflicts of interest. “Successful collaborations not only acknowledge that conflicts can arise, but also commit to creating formal procedures for resolving them,” writes Steven Currall, the executive director for academic–corporate initiatives at Harvard University.

Highly targeted antibody-based treatments have been game-changing for people with moderate to severe psoriasis — a painful skin condition that also comes with a high risk of developing cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and arthritis, and can take a toll on mental health. But these antibody therapies, which selectively take out the inflammatory molecules that drive the disease, have a major drawback: they must be taken for life. Or at least that’s what was thought. Now large clinical trials are trying to find out why some people who have to cease treatment for other reasons remain psoriasis-free. “Ten years ago, I thought we wouldn’t cure psoriasis in my lifetime,” says clinical dermatologist Curdin Conrad. “Now, I think we’ll be able to cure some patients within the decade.”

This editorially independent article is part of Nature Outlook: Skin, a supplement produced with the financial support from LEO Pharma A/S.

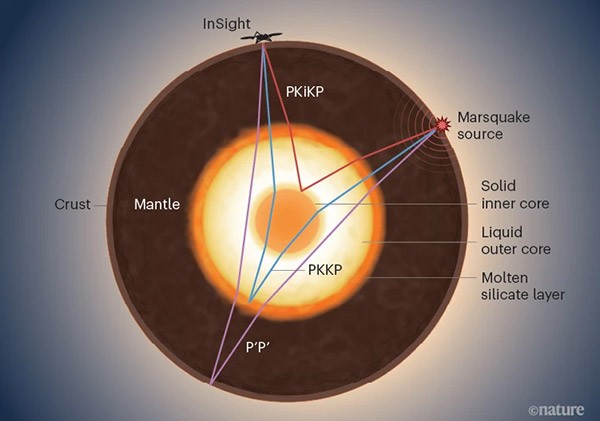

Infographic of the week

Data from NASA’s InSight lander suggests that Mars has a small, solid inner core about 600 kilometres across. InSight detected the seismic waves that passed through the planet’s layers during marsquakes, giving scientists a glimpse beyond its rocky crust and mantle, and the liquid outer layers of its core. “The presence of an inner core in Mars and the lack of a magnetic field in the present day suggests that the crystallization mechanism that drives the creation and evolution of the inner core is proceeding slowly,” writes planetary scientist Nicholas Schmerr. (Nature | 8 min read)

Briefing readers know that once you have seen two molluscs mate, you will never forget it. Illustrator Giselle Clarkson thought it was an experience not to be missed for Ned, a common garden snail (Cornu aspersum) with a very unusual left-spiralling shell that she found in her garden. Ned’s mirror-image body means its reproductive organs are also reversed — requiring an equally opposite mate. Should you spot a likely lover, Clarkson and New Zealand Geographic have started a campaign to find Ned’s perfect match.

While we all root for Ned, why not take a moment to let me know your feedback on this newsletter? Your e-mails are always welcome at [email protected].

Thanks for reading,

Flora Graham, senior editor, Nature Briefing

• Nature Briefing: Careers — insights, advice and award-winning journalism to help you optimize your working life

• Nature Briefing: Microbiology — the most abundant living entities on our planet — microorganisms — and the role they play in health, the environment and food systems

• Nature Briefing: Anthropocene — climate change, biodiversity, sustainability and geoengineering

• Nature Briefing: AI & Robotics — 100% written by humans, of course

• Nature Briefing: Cancer — a weekly newsletter written with cancer researchers in mind

• Nature Briefing: Translational Research — covers biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma