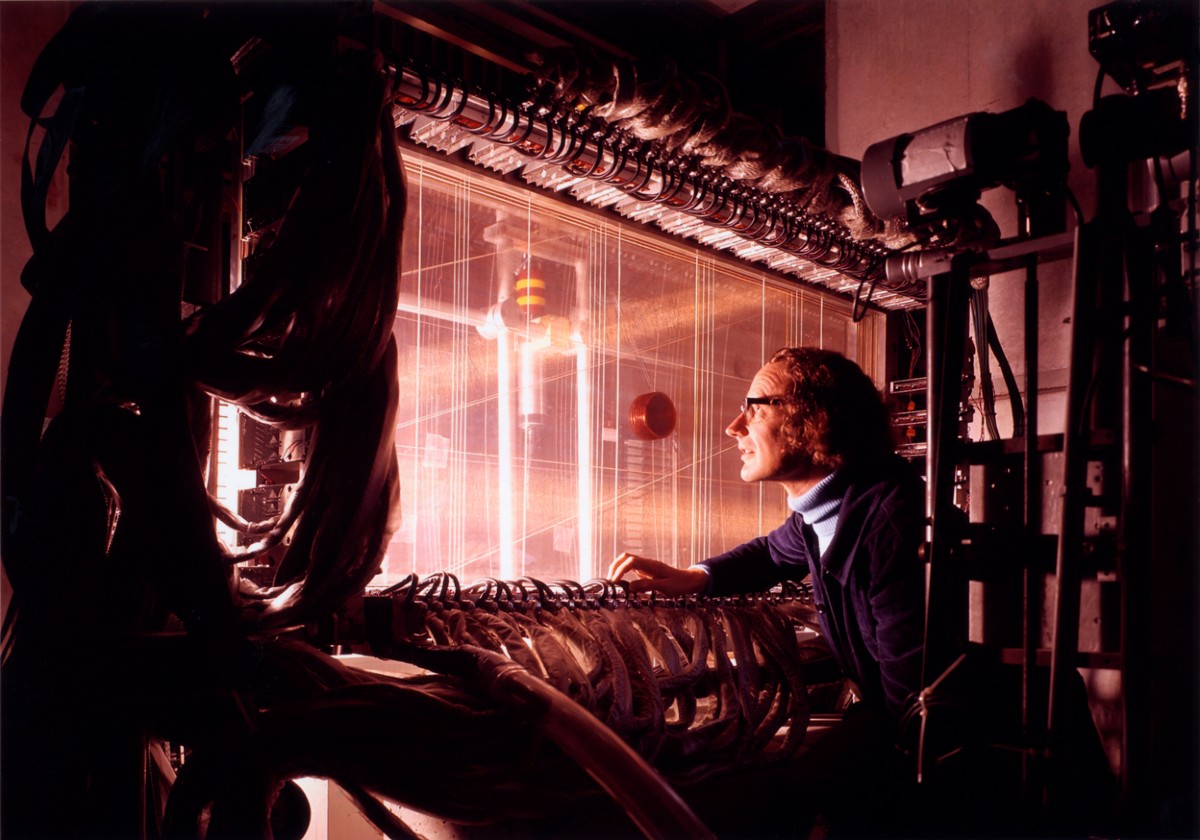

Running experiments as part of a career journey can be as productive as time in the lab.Credit: CERN/Science Photo Library

In 2024, one of us (M.B.) stepped into a writing workshop run by the other. As we chatted after the session, it became clear that we had both navigated dramatic career shifts, sometimes following an impulse, and other times more deliberately. We realized that we were both drawn to the idea of rethinking career paths as a process of experimentation.

For A.-L.L.C., this began in 2017, when she left her job in digital health at Google’s campus in Mountain View, California. She simply quit — no plan, no safety net, just the conviction that this career wasn’t right for her. The loss of her work identity and the financial stress that followed were anxiety-inducing, and she regretted taking the jump without fully considering what to explore next.

In 2019, while in a neuroscience master’s programme at King’s College London, A.-L.L.C. grew curious about science communication, so she decided to try a career experiment, rather than make an impulsive leap. Inspired by scientific methodology, she designed a test and trial phase: writing 100 articles on a wide range of topics in 100 days for her personal website.

During career exploration, small, intentional experiments, such as this one, can turn uncertainty into insight and shrink the psychological distance between the current situation and what comes next.

Charting a new course

Because English wasn’t her first language, A.-L.L.C. had significant doubts about whether she could translate complex research into engaging content. But over those 100 days, she discovered unexpected benefits: the joy of feedback from readers and developing skills she hadn’t anticipated, such as visual storytelling and building a dedicated following and community. Most importantly, the experiment shifted her perspective. She realized that her career path didn’t have to be an either–or choice between researcher and science communicator. In fact, the synergy between the roles made her stronger in both.

Anne-Laure Le CunffCredit: Vanity Studios

Similarly, after 17 years on an academic path with the goal of becoming a professor in neuroscience, M.B., then based at the University of Magdeburg, Germany, found himself increasingly curious about start-ups and how research could be applied to build technological solutions. But instead of leaving research for something unfamiliar, he began exploring his interest while still in academia, treating his exploration of the start-up world as an experiment.

In 2019, he started a new project: every Friday for six weeks, he reached out to a neuroscience-focused start-up to arrange informal coffee chats. One that stood out was MedEngine, a Berlin-based company developing Flytta, a tool for passively tracking motor and non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. The firm’s work overlapped with his own research, and they began exploring ways to collaborate. Later that year, MedEngine provided input on a successful grant application that M.B. led, one aspect of which was using Flytta for the early detection of Parkinson’s disease. The experience helped him to establish his first connections with the start-up world while remaining rooted in academic research.

Then, in 2020, M.B. began a new experiment — working five hours a week as a scientific editor at the health-tech start-up neotiv in Magdeburg, Germany, gaining experience translating research findings to create an app for the early detection of memory problems related to Alzheimer’s disease. That first step led him to co-found his own start-up, Alois — a digital companion that sets reminders and stores memories as voice notes to help people with early-stage dementia to maintain their independence. After meeting his co-founders at a hackathon, they began working on the idea. They soon after joined an incubator programme while M.B. was still in academia.

The start-up didn’t work out, but the experience was invaluable. It highlighted the differences between business and academia: decisions had to be made quickly and with limited information; collective teamwork took precedence over individual expertise; and, most significantly, the focus was on solving a real problem, not just advancing knowledge.

How to run an experiment

The goal of a career experiment isn’t to land your next job — it’s to learn. Experiments can lead you down curiosity-driven rabbit holes and open up unexpected paths. Just like in research, some will confirm your hypothesis, and others will disprove it. In fact, a ‘failed’ career experiment can be just as clarifying as a successful one by helping you to rule things out.

Matthew Betts

For both of us, this experimental approach has led us to varied and interesting roles. A.-L.L.C.’s career experiment became the foundation for the Ness Labs newsletter, which today has more than 100,000 subscribers, and led to her book, Tiny Experiments, published this year. She has remained in academia, working as a neuroscience researcher at King’s College London. M.B. now runs MJB Consulting in Berlin, his own health-tech consultancy, and leads guided workshops for PhD students and postdocs on curiosity-driven career experimentation.

Here are five tips for crafting a career experiment:

Choose your hypothesis. Decide what question you’re asking, and how you can frame it to create a clear test. For example: “Do I enjoy translating research for industry?”, “Am I energized by mentoring and teaching?” or “Does consulting work align with my skill set?”