A brain scan (artificially coloured) produced by magnetic resonance imaging. Credit: K H Fung/Science Photo Library

A brain implant can decode a person’s internal chatter – but the device works only if the user thinks of a preset password1.

The mind-reading device, or brain–computer interface (BCI), accurately deciphered up to 74% of imagined sentences. The system began decoding users’ internal speech – the silent dialogue in people’s minds — only when they thought of a specific keyword. This ensured that the system did not accidentally translate sentences that users would rather keep to themselves.

The study, published in Cell on 14 August, represents a “technically impressive and meaningful step” towards developing BCI devices that accurately decode internal speech, says Sarah Wandelt, a neural engineer at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in Manhasset, New York, who was not involved in the work. The password mechanism also offers a straightforward way to protect users’ privacy, a crucial feature for real-world use, adds Wandelt.

Avoiding eavesdropping

BCI systems translate brain signals into text or audio and have become promising tools for restoring speech in people with paralysis or limited muscle control. Most devices require users to try to speak out loud, which can be exhausting and uncomfortable. Last year, Wandelt and her colleagues developed the first BCI for decoding internal speech, which relied on signals in the supramarginal gyrus, a brain region that plays a major part in speech and language2.

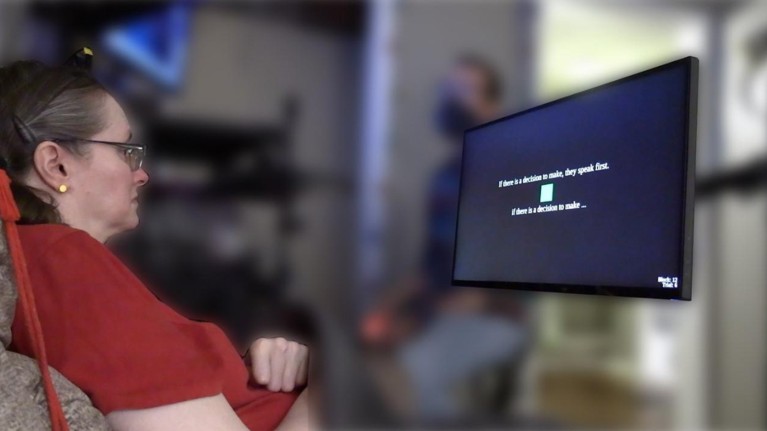

A study participant who has trouble speaking clearly because of a stroke uses the brain–computer interface.Credit: Emory BrainGate Team

But there’s a risk that these internal-speech BCIs could accidentally decode sentences users never intended to utter, says Erin Kunz, a neural engineer at Stanford University in California. “We wanted to investigate this robustly,” says Kunz, who co-authored the new study.

First, Kunz and her colleagues analysed brain signals collected by microelectrodes placed in the motor cortex — the region involved in voluntary movements — of four participants. All four have trouble speaking, one because of a stroke and three because of motor neuron disease, a degeneration of the nerves that leads to loss of muscle control. The researchers instructed participants to either attempt to say a set of words or imagine saying them.

Recordings of the participants’ brain activity showed that attempted and internal speech originated in the same brain region and generated similar neural signals, but those associated with internal speech were weaker.

Brain implant translates thoughts to speech in an instant

Next, Kunz and her colleagues used this data to train artificial intelligence models to recognize phonemes, the smallest units of speech, in the neural recordings. The team used language models to stitch these phonemes together to form words and sentences in real time, drawn from a vocabulary of 125,000 words.

The device correctly interpreted 74% of sentences imagined by two participants who were instructed to think of specific phrases. This level of accuracy is similar to that of the team’s earlier BCI for attempted speech, says Kunz.