While competing manufacturers from motorsport’s fledgling days, like Peugeot and Renault, have survived into the 21st century, the drivers of the late 19th century have faded from popular memory. The behind-the-wheel stars of that bygone century were as famous as their counterparts today, and millions of people followed their lives in and out of competition through newspapers. One incident immortalized on newsprint was when Albert Lemaître, the winner of the 1894 Paris-Rouen, stood trial for murdering his wife a dozen years after his historic victory. Despite admitting to committing the heinous act, Lemaître’s attorney was able to convince the jury to acquit him using a now-antiquated defense, a crime of passion. The only thing that was missing was a low-speed car chase across Paris.

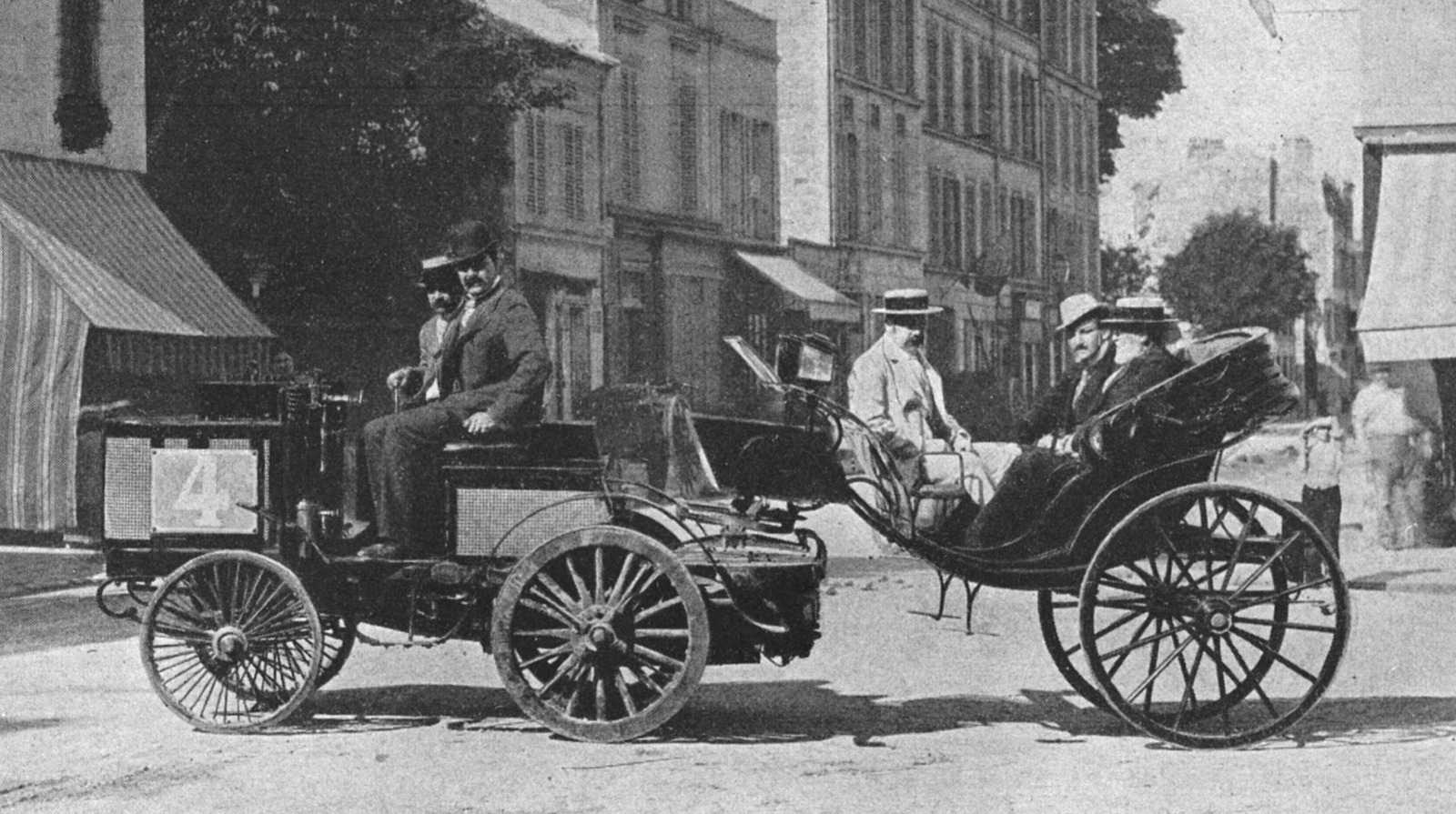

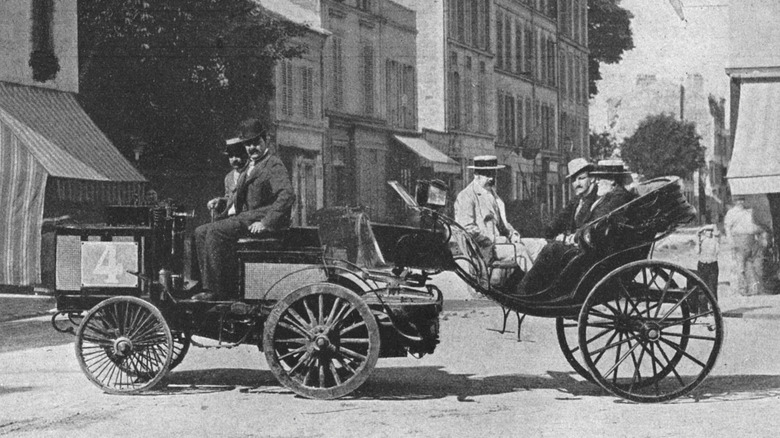

The 1894 Paris-Rouen was the first organized competitive motor race. Earlier events often touted as the first ever race featured lumbering steam-powered road-going locomotives that couldn’t be realistically operated by a single person. Le Petit Journal, Paris’ leading newspaper and the race’s organizer, imposed regulations that favored true automobiles, a vehicle intended for personal use by an individual. These requirements controversially secured the victory for Lemaître. Comte Jules-Albert de Dion was the first to complete the 78-mile course from the French capital to Normandy with a time of six hours, 48 minutes. However, officials disqualified the Comte de Dion’s steam-powered car because it required a second person to operate; a stoker to tend the boiler’s fire. The victory was awarded to the 30-year-old Lemaître, the second-place finisher. His Peugeot Type 7, powered by a 3.7-horsepower Daimler engine, crossed the line three minutes behind De Dion.

The disqualification sparked a grudge that launched the Tour de France

The victory wasn’t a life-changing achievement. The appeal of these early contests was based on the novelty of early cars and the members of high society competing. Drivers were a few years away from becoming celebrities solely through winning races. Lemaître, a merchant’s son, raced as a lavish pastime while working as a champagne exporter. He continued competing for the rest of the 1890s, but never claimed another major win. Admittedly, the manufacturers had the most on the line.

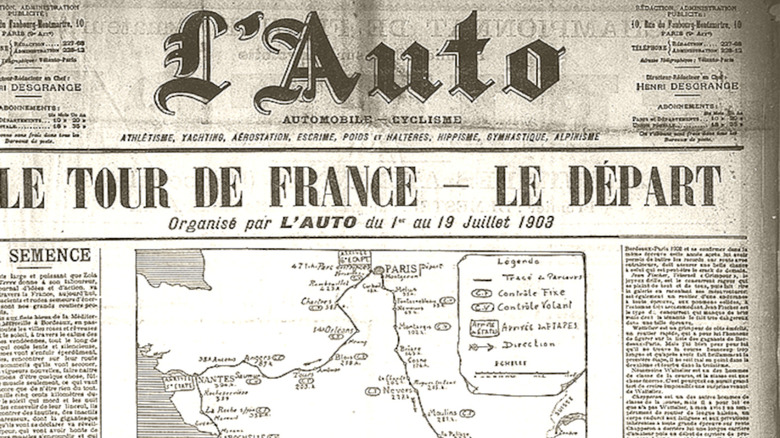

The disqualification sparked a grudge between the Comte de Dion and Pierre Giffard, Le Petit Journal‘s editor. The nobleman co-founded one of the world’s largest automakers back then, De-Dion-Bouton, and was racing a vehicle produced by the company. Later that year, the grudge would become a full-blown feud as the two ended up backing opposite sides in the Dreyfus affair, an antisemitic political scandal that rocked France for the next decade. When Giffard left Le Petit Journal in 1896 to become the editor of Le Vélo, the Comte de Dion sought to shutter the progressive sports newspaper. He partnered with tire magnate Édouard Michelin and industrialist Adolphe Clément to launch a rival sportspaper, L’Auto. While unsuccessful at first, their fortunes changed after L’Auto founded a bicycle race in 1903, the Tour de France. According to “The Tour de France: A Cultural History”, the race’s inaugural edition more than tripled the newspaper’s circulation. Le Vélo closed up shop the following year.

L’Équipe, the post-World War II successor of L’Auto, is still in print today as France’s largest daily sports newspaper. Its sister company, Amaury Sport Organisation, organizes the Tour de France as well as the Dakar Rally.

If his heart broke, then you can’t send him to the rope

Lemaître’s name would appear on the pages of Parisian newspapers multiple times in 1906. The September 7 issue of most papers covered his murder trial at the Seine Court of Assizes. In late February, his wife Lucie Lemaître had filed for divorce. She had reconnected with a former fiancé and rekindled their romance. Albert and Lucie had been married since 1900. A few weeks after leaving him, she asked to return to pick up her belongings. He agreed. When Lucie returned and an argument broke out after he pleaded for her to stay. According to Le Figaro‘s account of the trial, Lucie said, “No, I don’t want you anymore. Besides, I don’t need your dirty money; I’m getting everything I need.” Lemaître then grabbed a revolver and fired three shots. He shot Lucie twice before turning the gun on himself, shooting himself in the head. Lucie died, but he recovered from his injuries. After hearing the news of Lucie’s murder, the former fiancé committed suicide by shooting himself.

Contemporary reporting had nothing but praise for the eloquent defense mounted by Lemaître’s defense attorney, Mr. Dussyanne. This trial’s equivalent of a black leather glove was a letter that Lemaître sent to Lucie just days before the murder and attempted suicide. Dussyanne read the letter before the court in which his client begged his wife not to leave him. He admitted in the letter that he would kill himself if she didn’t stay and that he’d like one last kiss before committing suicide. It was enough evidence to convince the jury to acquit Lemaître on the basis that it was a crime of passion, meaning his emotional state impacted his ability to think rationally. The court’s audience applauded the verdict.

Yes, prosecutors couldn’t stand the crime of passion defense

If you’re frustrated that someone could get away with murder to a round of applause, you’re not the only one. The French Ministry of Justice was frustrated that juries would consistently use “crime of passion” as a means of acquitting defendants. According to a paper in the Journal of Social History, a ministry statistician in 1894 found that the acquittal rate for murders soared from 15% to 34% between 1860 and 1890. For assaults, the acquittal rate went from 27% to 78%. The prevailing theory in the 1890s was that juries believed that the potential sentences for defendants were too harsh.

The jury also might not have viewed Lucie as a victim for leaving her husband. Lucie calling Lemaître’s money dirty is a line that stands out in the trial’s coverage. Again, Lemaître was a champagne exporter. Like in the United States, there was a temperance movement in 1900s France that was closely associated with the women’s suffrage movement. When the French Union for Women’s Suffrage formed in 1909, the organization promoted itself with the tagline, “French women want to vote – against alcohol, slums and war.” While a prohibition was never imposed, the country would ban absinthe in 1915. France would be one of the last countries in Europe to enact women’s suffrage. Charles de Gaulle and the French Provisional Government granted women the right to vote in 1944 after the country’s liberation during World War II. To round things off, it took until 1975 for crimes of passion to be repealed from France’s penal code.