Attached to the Very Large Telescope in Chile, the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) allows researchers to probe the most distant galaxies. It’s a popular instrument: for its next observing session, from October to April, scientists have applied for more than 3,000 hours of observation time. That’s a problem. Even though it’s dubbed a cosmic time machine, not even MUSE can squeeze 379 nights of work into just seven months.

The European Southern Observatory (ESO), which runs the Chile telescope, usually asks panels of experts to select the worthiest proposals. But as the number of requests has soared, so has the burden on the scientists asked to grade them.

“The load was simply unbearable,” says astronomer Nando Patat at ESO’s Observing Programmes Office in Garching, Germany. So, in 2022, ESO passed the work back to the applicants. Teams that want observing time must also assess related applications from rival groups.

AI is transforming peer review — and many scientists are worried

The change is one increasingly popular answer to the labour crisis engulfing peer review — the process by which grant applications and research manuscripts are assessed and filtered by specialists before a final decision is made about funding or publication.

With the number of scholarly papers rising each year, publishers and editors complain that it’s getting harder to get everything reviewed. And some funding bodies, such as ESO, are struggling to find reviewers.

As pressure on the system grows, many researchers point to low-quality or error-strewn research appearing in journals as an indictment of their peer-review systems failing to uphold rigour. Others complain that clunky grant-review systems are preventing exciting research ideas from being funded.

These are long-standing concerns. Peer review has been accused of being a sluggish, gatekeeping, bias-laden enterprise for as long as it has existed. But some data show that dissatisfaction is growing. Added strain on the system, such as the explosion of publications following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, has prompted interest in methods to boost the speed and effectiveness of peer review, with experiments at journals ranging from paying reviewers to giving more structured guidance.

Others argue that peer review has become too unreliable. They suggest radical reform, up to and including phasing out the practice entirely.

More recent than you think

Although it is often described as the bedrock of scientific endeavour, peer review as it is performed today became widespread among journals and funders only in the 1960s and 1970s. Before then, the idea of refereeing manuscripts was more haphazard. Whereas some journals used external review, many editors judged what to publish entirely on the basis of their own expertise, or that of a small pool of academic experts, says Melinda Baldwin, a historian of science at the University of Maryland in College Park who has studied the development of peer-review systems in academia.

But with massive increases in public funds for research, the volume of manuscripts pushed editors at all journals towards external review, to avoid overwhelming a small pool of reviewers. Even now, external reviewing is far from a monolithic standard. Rather, it is a diverse collection of checking and selection practices that differ between journals, scholarly fields and funders.

Peer reviewers unmasked: largest global survey reveals trends

What emerged in the late twentieth century is now facing a similar crisis: too many manuscripts and not enough reviewers. The science system is churning out ever more research papers1, but the reviewer pool doesn’t seem to be growing fast enough.

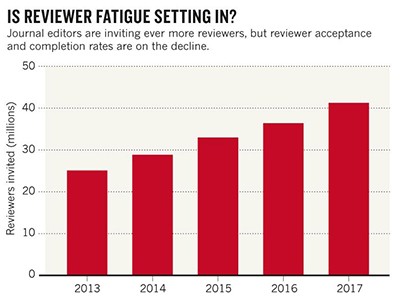

Evidence for the problem is largely anecdotal, because journals tend to keep their information private. But some data have emerged. In 2018, a report by the website Publons (now owned by the analytics firm Clarivate) analysed anonymized information from more than ten million manuscripts submitted during 2013–17 in a widely used peer-review workflow tool. The report found that, over time, editors had to send out more and more invitations to get a completed review (see go.nature.com/4k8xbfp). Publons, which also surveyed 11,000 researchers, warned of a rise in “reviewer fatigue”. More recently, fields from ophthalmology2 to microbiology3 have reported that more scientists are rejecting invitations to review. In a blog posted last month, analyst Christos Petrou, founder of the consultancy firm Scholarly Intelligence in Tokyo, analysed turnaround times for manuscripts across 16 major science publishers. He found that the average turnaround time from manuscript submission to acceptance is increasing — it is now at 149 days, compared with 140 in 2014: a rise of about 6% over the decade (see go.nature.com/4mkm29d).

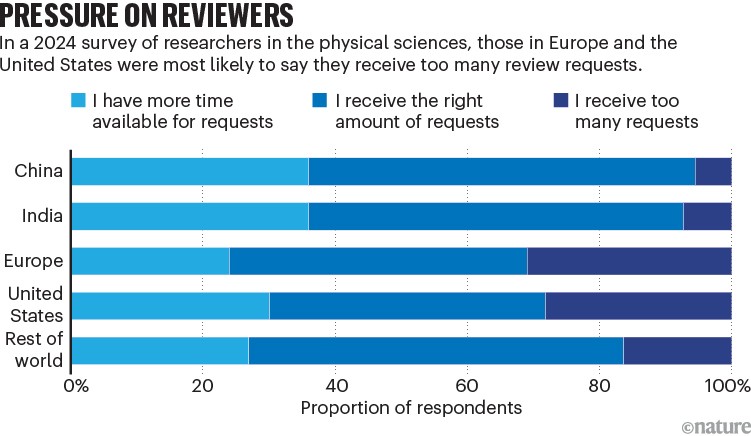

IOP Publishing, the publishing arm of the UK Institute of Physics in London, surveyed the experiences of researchers (mostly in the physical and environmental sciences) in 2020 and again in 2024. In 2024, half of the 3,000 or so respondents said that the number of peer-review requests they received had gone up over the previous three years (see go.nature.com/4h7gagv). On the encouraging side, only 16% said they received too many requests (down from 26% four years ago), but respondents from Europe and the United States were more likely to say this (see ‘Pressure on reviewers’).

Source: State of Peer Review 2024/IOP Publishing (https://go.nature.com/4JYSDTS)

Review rewards

Many experiments by funders and journals are aimed at incentivizing researchers to do more reviews, and getting them to send in their assessments more quickly.

Some journals have tried publicly posting review turnaround times, leading to a modest reduction in review completion time, mainly among senior researchers. Others hand out awards for productive reviewers, although there’s some evidence that such prizes led to reviewers completing fewer reviews in subsequent years, possibly because they felt they had done their bit4. Another idea is to change research-assessment practices: an April survey of more than 6,000 scientists by Springer Nature, which publishes Nature, found that 70% wanted their work evaluations to consider their peer-review contributions, but only 50% said they currently did so. (Nature’s news team is editorially independent of its publisher.)

The ultimate incentive might be financial. A debate about paying reviewers has swung to and fro for years. Supporters argue that it’s a fair reflection of the work and value that reviewers provide. In 2021, Balazs Aczel, a psychologist at Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest, and his colleagues estimated that reviewers worked for more than 100 million hours on reports in 20205. On the basis of the average salaries of academics, that’s a contribution worth billions of dollars. Critics, however, warn of conflicts of interests and perverse incentives if researchers are paid to review, and point out that most academics say they carry out reviewing duties in their salaried work time.

Potential reviewers rarely indicate why they refuse to review. But Aczel suggests that a growing number resent providing a free service that commercial publishers turn into profits. That point was made strongly by James Heathers, a science-integrity consultant based in Boston, Massachusetts, who in 2020 posted on a blog that he would accept unpaid review invitations only from society, community and other non-profit journals. Big publishers would receive an invoice for $450.

The move backfired, he jokes now. Although requests from commercial publishers stopped, those from the other categories went up.

Publishers trial paying peer reviewers — what did they find?

This year, two publications reported on the results of experiments to pay journal reviewers. Critical Care Medicine offered US$250 per report. Its trial, funded by the Canadian government, showed that the offer of payment made reviewers slightly more likely to take up requests (the proportion of invitations accepted rose from 48% to 53% ), with turnaround time boosted slightly from 12 to 11 days. Review reports were of comparable quality6. But the journal doesn’t have the resources to keep paying for reviews, says David Maslove, an associate editor on the journal and a critical-care physician at Queen’s University in Kingston, Canada.

By contrast, the Company of Biologists, a non-profit organization in Cambridge, UK, is continuing with paid review on its journal Biology Open after a successful trial. The journal paid reviewers £220 (US$295) per review, and — unlike Critical Care Medicine — told them it expected a first response within four days, to allow editors to decide on manuscript acceptance or rejection within a week of submission.

Every manuscript in the trial received a first decision within seven working days, with an average turnaround time of 4.6 business days7. That’s compared with the 38 days the journal was seeing with the standard review process. Journal staff agreed that review quality was upheld, says Biology Open’s managing editor, Alejandra Clark.

“If it is scalable, then we need to figure out how to finance it,” Clark says. “We would obviously like to avoid putting the burden on authors by increasing the APCs [article processing charges] to adjust some of the costs, but these are the discussions we’re having.”

Expanding the reviewer pool

Some funders are also struggling to get reviewers. “It has become increasingly difficult to find people who have the time or ability or want to assess our proposals,” says Hanna Denecke, a team leader at the Volkswagen Foundation, a private funder in Hanover, Germany. That’s despite reviewers being offered almost €1,000 (US$1,160) for a day’s work.

Like ESO, the Volkswagen Foundation has addressed this issue by asking applicants to review other proposals in the same funding round, a system called distributed peer review (DPR).

And on 30 June at a conference in London, UK funders announced a successful trial of DPR, which they showed could review grants twice as fast as a typical review process. To get around concern that reviewers might be negative about competitors, applications were split into pools. Researchers don’t review applications from their own pool and so can’t affect the chances of their own applications being accepted.

One reason the Volkswagen Foundation is keen on DPR is that it moves the decision-making away from senior and more established scientists. “One might say these are kind of gatekeepers who might keep other people out,” Denecke says.

Stop the peer-review treadmill. I want to get off

Straining under the weight of increased applications, some funders have turned to ‘demand management’ and will consider only one bid per university for a particular grant. But this just pushes the load of reviewing elsewhere, points out Stephen Pinfield, an information expert at the Research on Research Institute at University College London. “Institutions then have to run an informal peer-review process to choose which bid they can put forward. It’s just shifting the burden,” he says. Then there are the extra reviews of work and individuals that institutions must conduct to prepare for quality-assurance exercises, such as the UK Research Excellence Framework.

“Very few analyses of the peer-review system take this informal stuff into account at all. And yet it’s enormously time consuming,” Pinfield says.

Ultimately, the most scalable solution to the labour problem at funders and journals is to widen the pool of reviewers. The bulk of the growth in research papers that need reviewing comes from authors in less-established scientific nations, points out Pinfield, whereas reviewers tend to be drawn from the same pool of senior academic experts in the West.

A 2016 study suggested that 20% of scientists did between 69% and 94% of the reviewing the previous year8. “The peer-reviewer pool is smaller than the author pool,” Pinfield says. “I think people are feeling that pressure.”

One issue is that editors naturally gravitate towards asking reviewers who they think do a good job and send reports on time. By expanding their pool of reviewers, they might end up with reviews that are of lower quality or less accurate — a point made by biologist Carl Bergstrom at the University of Washington in Seattle and statistician Kevin Gross at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, in an analysis of the pressures on peer review. Their work was posted as a preprint in July9.

Many science publishers are now using technology to help automate the search for a wider pool of reviewers. In 2023, for instance, a tool that allows editors to search the Scopus database to find reviewers on the basis of subject expertise and other criteria was integrated into the Editorial Manager manuscript system used by many journals worldwide. Other publishers have launched similar software.

Another idea that’s catching on is joint review: an established academic is paired with an early-career researcher, which brings in a new reviewer and trains them at the same time.

Improving efficiency and quality

One way to make reviewing more efficient — and perhaps improve quality — is to give referees a series of clear questions to address. This format is known as structured peer review.

Last year, researchers published the results of a rigorous test of how referees respond to this idea.

“As an editor, you get peer-review reports that are not always thorough. Structured peer review is an attempt to actually focus them on questions that we want answers to,” says Mario Malički, a publication-practices specialist at Stanford University in California and co-editor-in-chief of the journal Research Integrity and Peer Review. He did the research with Bahar Mehmani, a publishing-innovation manager at Elsevier in Amsterdam.

In August 2022, Elsevier ran a pilot in which it asked reviewers to address nine specific questions when they assessed papers submitted to 220 journals. Malički and Mehmani looked at a sample of these manuscripts that had been assessed by two independent reviewers. They found that reviewers were more likely to agree with each other on final recommendations, such as whether the data analysis was correct and the correct experiments carried out, than in manuscripts assessed before the trial started10. (Reviewers still didn’t agree often, however: agreement was 41%, up from 31% before the trial.)

Elsevier now uses structured peer review at more than 300 of its journals. Other journals have instituted variants on the idea.

Asking questions seems to help expose gaps in review knowledge, Malički adds, with referees more likely to say that someone else should check technical aspects such as the statistics or the modelling.

Boosting the quality of reviews is also an argument made by those pushing for greater transparency in the peer-review system – by encouraging journals to publish reports alongside published papers, and referees to put their name to them.

Transparent peer review to be extended to all of Nature’s research papers

Advocates argue that this could boost the status of review reports and so encourage more people to agree to write them. And it could also help to address the criticism that many journals publish shoddy research, which lessens trust in the rigour of the peer-review process writ large. Working out whether reviewers have made an honest attempt to examine a paper or simply waved it through with little scrutiny is hard, because peer review at journals has conventionally been confidential.

Pinfield agrees that publishing reviews could boost quality: “If reviewers know their work is going to be made publicly available, it is reasonable to assume that they will ensure the quality of the review is good.”