A study published in 2022 by a team including African scientists showed that, in Kenyan women aged 15–20, one dose of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is as effective as multiple doses (R. V. Barnabas et al. N. Engl. J. Med. Evid. 1, EVIDoa2100056; 2022). Vaccination is crucial for preventing HPV infections, the main cause of cervical cancer, which kills more than 300,000 people worldwide each year.

Owing to this and other similar findings, in 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that medical caregivers switch from giving girls and young women the standard of three doses of the HPV vaccine to just one or two, depending on availability. This has saved millions of lives by reducing the costs and logistical challenges of vaccination (K. Prem et al. BMC Med. 21, 313; 2023). Yet, I suspect that — as with many other notable contributions that African scientists have made to global knowledge — hardly anyone in Africa has heard about this research.

Science communication will benefit from research integrity standards

Across Africa, there are very few outlets for science journalism. I work in Kenya on infectious disease. Here, The Daily Nation, the country’s most widely read newspaper, publishes a section on health just once a week, mainly highlighting health-care policies and reforms. Breaking news related to scientific discoveries appears only a handful of times a year.

Few journalists in Africa are trained in science. From what I’ve seen, even fewer researchers are trained in science communication.

Science-communication training has been offered in Europe and the United States for decades. Yet, in Kenya and many other African countries with considerable scientific output, such as Egypt, Nigeria and Uganda, no universities provide science-communication courses. (Training programmes are available in South Africa.)

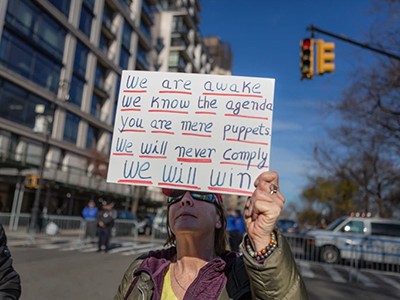

Misinformation poses a bigger threat to democracy than you might think

To try to spur a nation-wide conversation about science communication in Kenya, I organized a workshop in Nairobi last year with the support of various partners, including the University of California, Santa Cruz, which offers a well-regarded science-communication programme. Before the workshop, many of the 40 participants hadn’t even realized that a career in science communication was a possibility. This gap needs addressing.

During the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Kenya, conspiracy theories and misinformation spread rapidly through social media. Some religious leaders discouraged their congregants from wearing masks and getting vaccinated, thinking that the disease was a form of divine punishment for sinners. Conspiracy theories similarly spread across Uganda during its 2022 Ebola outbreak.

Currently, there is little climate-change denial in Kenya and other African nations. But as extreme weather events increasingly affect communities, there will be a higher risk of anti-climate messages being imported, particularly from the United States. In fact, some people received thousands of US dollars in donations — often from individuals with links to fossil-fuel interests — after posting debunked climate-change conspiracy theories.