As the world grapples with difficult challenges — including how to manage water and the environment, help people to lead healthy lives, cope with climate change and develop technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) — fresh policy thinking is urgently needed. For the past ten years, the European Union has been trialling an unusual approach to gaining diverse perspectives, by bringing together scientists, artists, policymakers and the public through a series of transdisciplinary projects.

The SciArt Project was launched by the Joint Research Centre (JRC) of the European Commission in 2016 (see go.nature.com/4nv92cd). Unlike conventional art–science collaborations, SciArt includes policymakers from the beginning, and gathers input from communities. The goal is to produce more human-centred policies, for example, by better addressing the realities of how communities are affected by wildfires or water pollution, or how people can live alongside nature in conservation areas.

Here we outline how the project works and share some of its successes.

Open to learning

The project operates through thematic cycles called Resonances, each focusing on a priority area that is aligned with the EU’s objectives. For instance, the NaturArchy cycle, which ran from 2022 to 2024, focused on issues linked to the European Green Deal, including the legal rights of nature, nature-based solutions, Indigenous knowledge and economics beyond growth.

Science could solve some of the world’s biggest problems. Why aren’t governments using it?

Each cycle provides an opportunity for artists to immerse themselves in the research being conducted at the JRC, allowing them to develop works that reflect and question the policy implications of scientific advancements. In turn, scientists and policymakers are exposed to creative ways of thinking that challenge conventional methods and open up unusual possibilities for research and policy formulation1.

SciArt projects unfold through a carefully structured process, starting with an open call for artists to respond to a curatorial statement linked to a specific theme. Workshops, lectures and dialogues follow. These are held at a transdisciplinary summer school, where artists, scientists, scholars, curators and policymakers meet to discuss ideas and explore the intersections of their work.

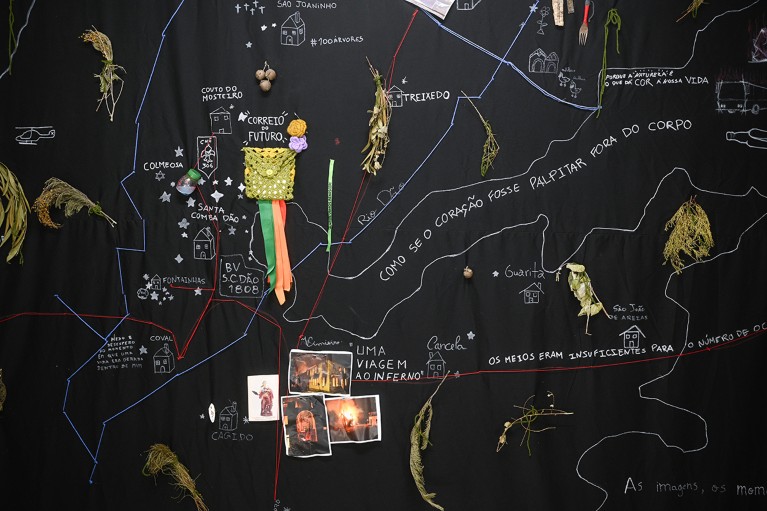

After the summer school, the artists enter a residency phase, during which they work closely with their scientific or policy counterparts to jointly develop an artwork grounded in research that reflects the issues discussed. Over the years, this collaborative process has produced 54 artworks and scores of community-engagement projects, often resulting in scientific innovation and spilling over into policies (see ‘Fresh perspectives’).

Through performances and immersive experiences, citizens can participate in dialogues about sustainability; policymakers can then use these insights to inform legislation that addresses public concerns. Through workshops, sensory experiences and storytelling, art–science collaborations allow people to reflect on their relationship with the environment, promoting behavioural shifts.

For example, the Haunted Waters project (see go.nature.com/42khtd2) showcases a cocktail bar of samples of contaminated water, each sent to the artist by a member of the public, alongside the sender’s personal story of that water body — thus blending citizen science with storytelling and myth. The bar’s visitors can learn about the main causes of chemical contamination in each sample by leafing through a menu. Haunted Waters sparks discussions on the difficulties of providing scientific advice on and designing policies to regulate thresholds of chemical cocktails in rivers and lakes.

Contaminated water samples sent in by contributors are on display in the installation Haunted Waters.Credit: Nonhuman Nonsense