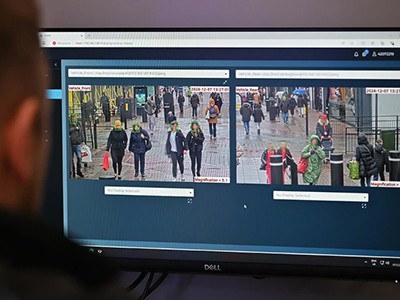

London’s police force is expanding its use of facial-recognition technology in public places.Credit: Leon Neal/Getty

The nature of scientific progress is that it sometimes provides powerful tools that can be wielded for good or for ill: splitting the atom and nuclear weapons being a case in point. In such cases, it’s necessary that researchers involved in developing such technologies participate actively in the ethical and political discussions about the appropriate boundaries for their use.

Read the paper: Computer-vision research powers surveillance technology

Computer vision is one area in which more voices need to be heard. This week in Nature, Pratyusha Ria Kalluri, a computer scientist at Stanford University in California, and her colleagues analysed 19,000 papers published between 1990 and 2020 by the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) — a prestigious event in the field of artificial intelligence (AI) concerned with extracting meaning from images and video. Studying a random sample, the researchers found that 90% of the papers and 86% of the patents that cited those articles involved imaging humans and their spaces (P. R. Kalluri et al. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08972-6; 2025). Just 1% of papers and 1% of patents involved only non-human data. This study backs up with clear evidence what many have long suspected: that computer-vision research is being used mainly in surveillance-enabling applications. The researchers also found that papers involving analysis of humans often refer to them as ‘objects’, which obfuscates how such research might ultimately be applied, the authors say.

This should give researchers in the field cause to interrogate how, where and by whom their research will be applied. Regulators and policymakers bear ultimate responsibility for controlling the use of surveillance technology. But researchers have power too, and should not hesitate to use it. The time for these discussions is now.

Wake up call for AI: computer-vision research increasingly used for surveillance

Computer vision has applications ranging from spotting cancer cells in medical images to mapping land use in satellite photos. There are now other possibilities that few researchers could once have dreamed of — such as real-time analysis of activities that combines visual, audio and text data. These can be applied with good intentions: in driverless cars, facial recognition for mobile-phone security, flagging suspicious behaviour at airports or identifying banned fans at sports events.

This summer, however, will see the expanding use of live facial-recognition cameras in London; these match faces to a police watch list in real time. Hong Kong is also installing similar cameras in its public spaces. London’s police force say that its officers will physically be present where cameras are in operation, and will answer questions from the public. Biometric data from anyone who does not have a match on the list will be wiped immediately.

Computer-vision research is hiding its role in creating ‘Big Brother’ technologies

But AI-powered systems can be prone to error, including biases introduced by human users, meaning that the people already most disempowered in society are also the most likely to be disadvantaged by surveillance. And, ethical concerns have been raised. In 2019, there was backlash when AI training data concerning real people were found to have been created without their consent. There was one such case at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, involving two million video frames of footage of students on campus. Others raised the alarm that computer-vision algorithms were being used to target vulnerable communities. Since then, computer-science conferences, including CVPR and NeurIPS, which focuses on machine learning, have added guidelines that submissions must adhere to ethical standards, including taking special precautions around human-derived data. But the impact of this is unclear.

According to a study from Kevin McKee at Google DeepMind, based in London, less than one-quarter of papers involving the collection of original human data, submitted to two prominent AI conferences, outlined that they had applied appropriate standards, such as independent ethical review or informed consent (K. R. McKee IEEE-TTS 5, 279–288; 2024). Duke’s now-retracted data set still racks up hundreds of mentions in research papers each year.

Science that can help to catch criminals, secure national borders and prevent theft can also be used to monitor political groups, suppress protest and identify battlefield targets. Laws governing surveillance technologies must respect fundamental rights to privacy and freedom, core to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Is facial recognition too biased to be let loose?

In many countries, legislation around surveillance technologies is patchy, and the conditions surrounding consent often lie in a legal grey area. As political and industry leaders continue to promote surveillance technologies, there will be less space for criticism, or even critical analysis, of their planned laws and policies. For example, in 2019, San Francisco, California, became the first US city to ban police use of facial recognition. But last year, its residents voted to boost the ability of its police force to use surveillance technologies. Earlier this year, the UK government renamed its AI Safety Institute; it became the AI Security Institute. Some researchers say that a war in Europe and a US president who supports ‘big tech’ have shifted the cultural winds.

For Yves Moreau, a computational biologist at the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium who studies the ethics of human data, the rise of surveillance is an example of ‘technological somnambulism’, in which humans sleepwalk into use of a technology without much reflection.

Publishers should enforce their own ethical standards. Computer-vision researchers should refer to humans as humans, making clear to all the possible scope of their research’s use. Scientists should consider their own personal ethics and use them to guide what they work on. Science organizations should speak out on what is or is not acceptable. “In my own work around misuse of forensic genetics, I have found that entering the social debate and saying ‘this is not what we meant this technology for’, this has an impact,” says Moreau. Reflection must happen now.