Union members protest against federal cuts at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan, in April 2025.Credit: Jim West/Getty

The administration of US President Donald Trump is hacking away at funding for research institutions — aiming, it says, to eliminate waste and bias in government-funded research. This is disrupting science in ways that are rippling well beyond laboratories and lecture halls. Here, Nature’s Careers team looks into some of the figures that might indicate wider disruptions to the scientific enterprise.

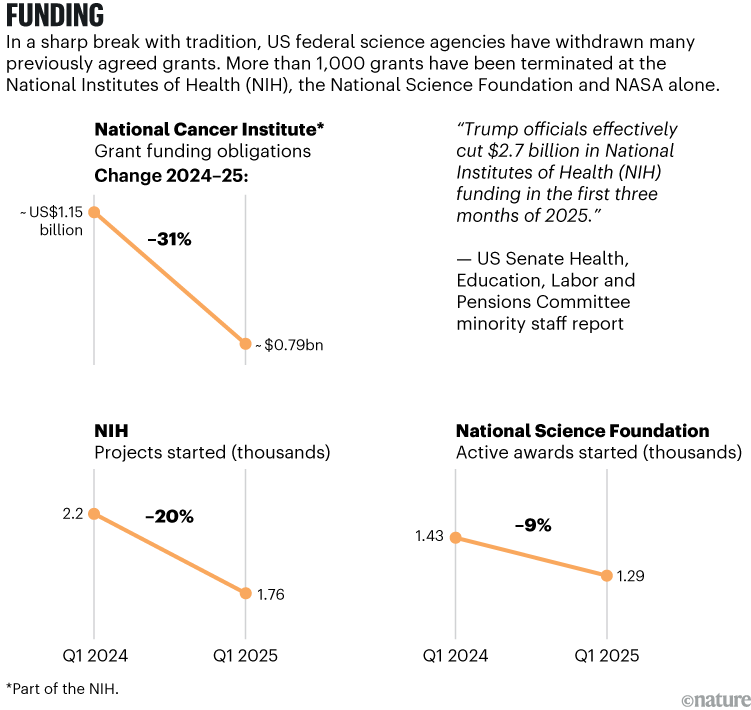

The number of active grants awarded by federal funding bodies has fallen strikingly, and companies that provide products to scientists — from basic vials to sophisticated cell analysers — are reporting a downturn in demand from academic and government customers. Their concerns are exacerbated by the president’s announcements of tariffs on foreign imports, which have triggered retaliatory trade restrictions in other countries. Some companies are predicting price rises fuelled by increased import costs.

Most of the people who have directly lost grants are principal investigators, but early-career researchers are being affected as well, warns Jason Owen-Smith, a sociologist who leads the Institute for Research on Innovation and Science (IRIS) consortium at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Drawing on IRIS data, Owen-Smith estimates that nationwide, federal grants to universities support about 646,000 researchers. About 48% of those are students and trainees, he says.

People outside academia will also be affected. “A whole lot of businesses in a really wide range of industries, from local restaurants to construction companies to specialized manufacturing companies,” Owen-Smith says, “are going to see a hit to their bottom line as a result of the cuts.”

However, not all areas of scientific activity have declined in the first quarter of 2025 — some have even picked up. For instance, the US National Bureau of Economic Research in Cambridge, Massachusetts, published more working papers in January, February and March this year than in the same period of 2024. Globally, publication rates for preprints, journal articles and other research content also continue to increase, consistent with long-term trends. But publication takes time, so this method of measuring scientific output will be slower to reflect trends than will some other metrics.

At the end of the first quarter, just a few months into the Trump administration, uncertainty about the future of US science reigned, as Nature’s charts show. Some statistics are pulled from small subsections of the scientific enterprise, such as sales from a single supplier. Others, including the number of federal grants awarded to US scientists, reflect more fundamental shifts.

Overall, the picture is gloomy, says Andrew Castaldi, a market specialist at Temblor, a risk-assessment company based in Redwood City, California. “To me, the federal science funding cuts will make it harder for any industry to build off the work done by the scientists employed by the government,” he says. “No single entity has the capacity to make up what is lost. In effect, the private sector’s innovations will diminish.”

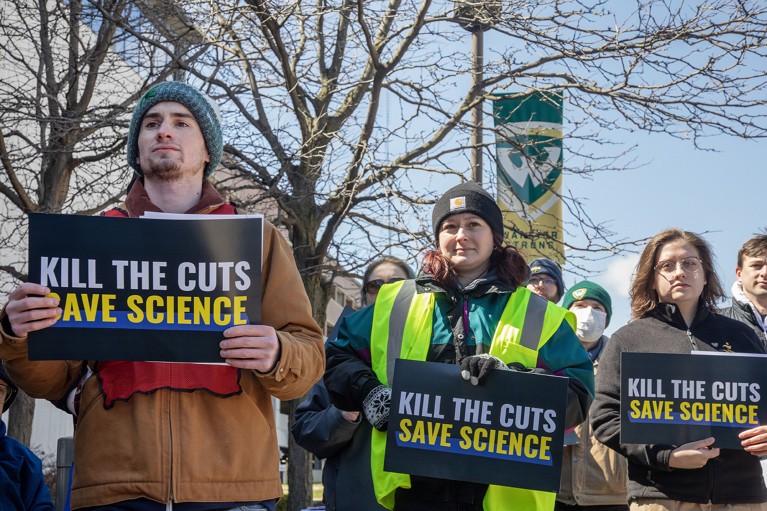

Grants withdrawn

US federal science agencies have retracted many grants (see ‘Funding’). More than 1,000 grants were terminated between 20 January and the end of March at three government agencies: the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Science Foundation (NSF) and NASA. Many more have been flagged for scrutiny on the grounds that they promote diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI), or because research in areas including vaccines and HIV is being de-emphasized. This is destabilizing careers.

Source: NIH Reporter; nsf.gov

The situation is changing fast, however. Since the end of March, many more grants have been cancelled. The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), of which the NIH is part, now lists more than 7,000 terminated contracts. But on 16 June, a US judge ruled that many of these cancellations were illegal, and ordered that they be restored. And Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachussetts, is locked in an ongoing legal battle with the federal government after its research funding was specifically targeted.

Supplier and demand

Falling revenues have affected scientific-product suppliers of every size (see ‘Lab equipment’). For some, a drop in US academic and government sales is offset by other sectors, so overall revenues have not declined. But even these companies are predicting future losses, which might have spooked investors.

Source: Agilent; Addgene; Avantor; Waters; BD; Thermo Fisher Scientific; Illumina; Bruker

Let’s get together

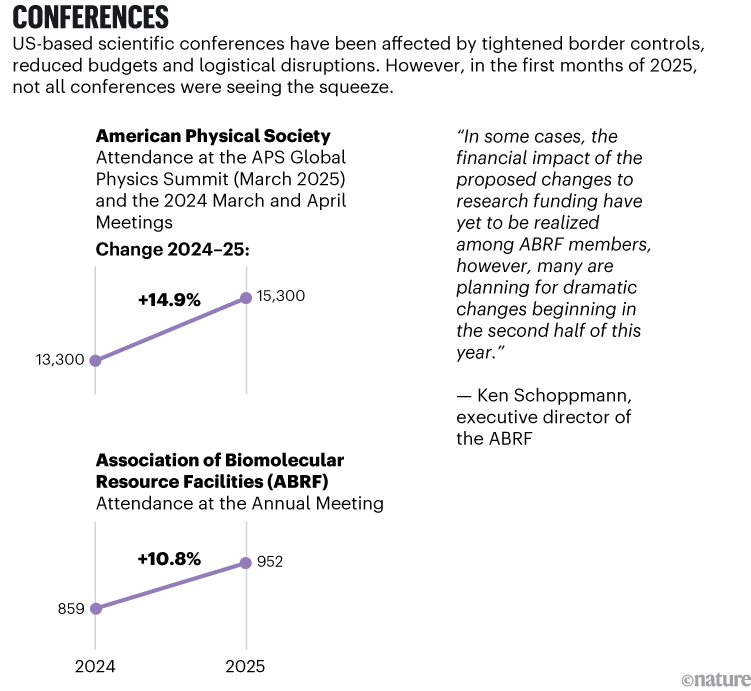

Some international researchers are reluctant to travel to the United States amid increases in border controls. Even US researchers are travelling less, given cuts in travel budgets at some institutions. And some conference organizers have had to postpone or cancel events, or relocate them to other countries. However, in the first three months of 2025, not all US-based scientific conferences had yet been affected (see ‘Conferences’).

Source: APS; ABRF

Lease on life sciences

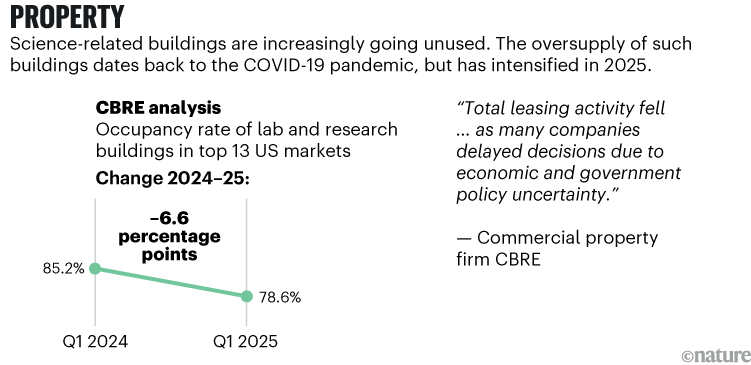

Nationwide, science-related buildings are standing empty (see ‘Property’). This is particularly notable in Boston, Massachusetts, where 25% of the lab or research and development (R&D) property inventory is vacant, compared with 14% in the previous year, according to the commercial property firm CBRE in Dallas, Texas.

The Boston–Cambridge area has a high concentration of universities, life-sciences companies and related vendors, and is the biggest US market for life-sciences property. Across the United States, demand for such buildings started to fall during the COVID-19 pandemic, but it has intensified in 2025. Companies are delaying leasing decisions owing to uncertainty, although some are looking to increase their US operations in response to tariffs on foreign manufacturing.

The effects will probably cascade into residential housing. Donna Ginther, an economist at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, anticipates a downturn in the property market, saying: “If you have fewer graduate students, it’s going to affect housing demand.”

Source: CBRE Insights report

Job cuts

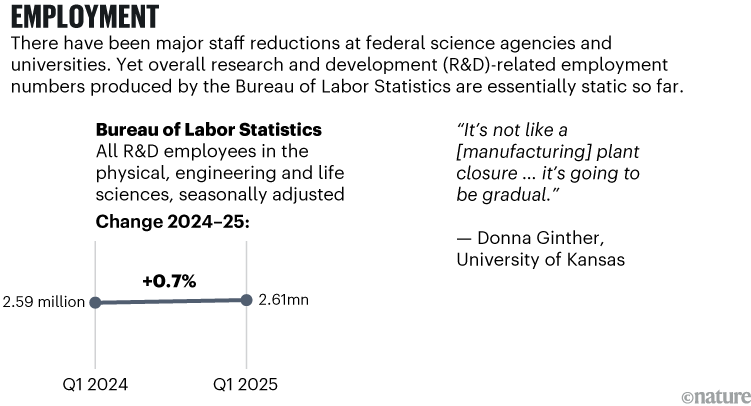

When it comes to employment, the larger effects of funding cuts and tariffs will take time to materialize, Ginther says. Thousands of staff positions have been cut from federal science agencies including the NIH, based in Bethesda, Maryland; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia; and the Food and Drug Administration, based in Silver Spring, Maryland. Yet overall R&D-related employment figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics barely shifted between the first three months of 2024 and the first three months of 2025 (see ‘Employment’).

Source: BLS Employment Statistics survey

Change might be coming. A spokesperson for the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston notes: “Payroll employment in the Boston–Cambridge–Newton metro area, which has a tech-heavy economy, is down 0.3% in March 2025 from one year earlier.” And some universities are cutting staff, students and programmes, whereas others are seeking stopgap solutions to funding shortfalls.