You have full access to this article via your institution.

Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

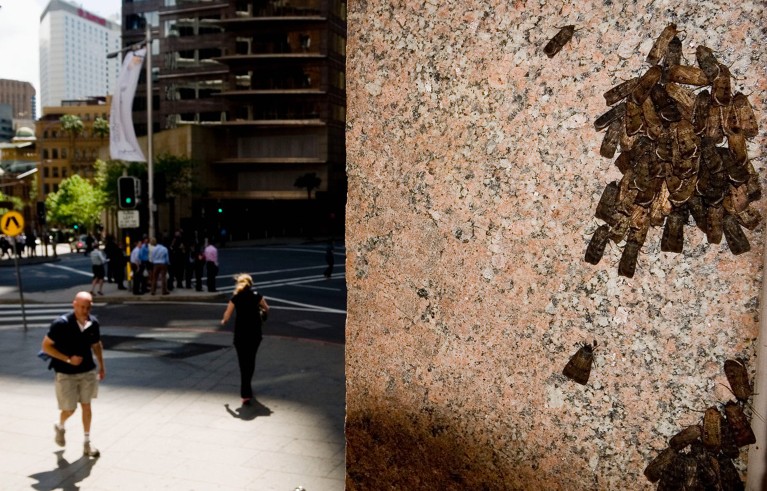

Bogong moths (Agrotis infusa) use the night sky to help navigate hundreds of kilometres.Credit: Tasso Taraboulsi/Polaris/eyevine

Bogong moths (Agrotis infusa) use the stars to navigate during long-haul travel — an ability previously identified only in humans, birds, and possibly seals. After emerging from their cocoons, the moths fly hundreds of kilometres across Australia to caves in the Australian Alps — caves they have never visited. Researchers tested the insects in a moth ‘flight simulator’ and found that they have two internal compasses: one using visual cues from the stars and another that relies on Earth’s magnetic field. The two skills act as fail-safes — the moths have an electromagnetic compass for cloudy nights, and a celestial one to use during events such as magnetic storms.

Researchers have used computer algorithms to design highly efficient synthetic enzymes from scratch, reducing the number of tedious hands-on experiments needed to perfect them. The products facilitate a chemical reaction that no known natural protein can, with an efficiency similar to that typically achieved by naturally occurring enzymes. One design was also 100 times more efficient than similar enzymes previously crafted using artificial intelligence. In comparison to enzymes that occur in nature, the algorithm’s creations are less complex and can’t grapple with multi-step chemical reactions, but they’re proof that the approach has promise.

The activity of certain neurons in the hypothalamus could be behind the impact that stress can have on sleep quality and memory. In mice, researchers found that stimulating neurons in a region called the paraventricular nucleus had a similar negative effect on sleep and performance in memory-related exercises to experiencing a stressful situation. Blocking these neurons helped the mice sleep a little better, and substantially boosted memory performance. Researchers say that treatments that target these neurons could slow the progression of psychiatric disorders that disrupt sleep and memory, such as post-traumatic stress disorder.

Reference: The Journal of Neuroscience paper

Ancient proteins and mitochondrial DNA extracted from the ‘Dragon Man’ fossil — a cranium found in northeastern China that is at least 146,000 years old — have confirmed that it belonged to a Denisovan, an archaic human group. The fossil is the first skull to be definitively linked to the group, which sheds light on what the ancient people looked like, putting an end to decade-long speculation.

Reference: Cell paper & Science paper

The ‘Dragon Man’ skull, shown here in a virtual reconstruction, had a prominent brow bone and was large enough to house a brain of a similar size to those of Neanderthals and modern humans. (Xijun Ni)

Features & opinion

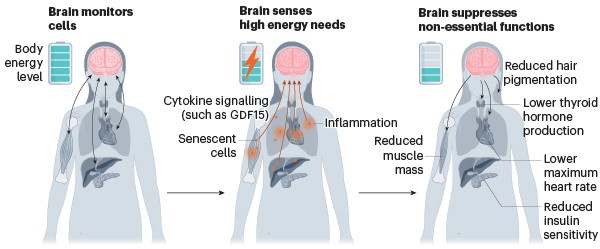

As people get older, a growing population of cells starts to consume more energy — perhaps because the cells accumulate damage that leads them to rev up processes such as inflammation. An emerging hypothesis suggests that the brain accommodates these energy-hogging ‘senescent cells’ by stripping resources from other biological processes, which ultimately results in outward signs of ageing, such as greying hair or a reduction in muscle mass. It’s one example of a growing understanding of how our brains control ageing and how psychological stress can accelerate the process at a molecular level.

As cells age and accumulate damage, some will enter a state of ‘senescence’. They secrete signalling molecules called cytokines, which indicate elevated energy demands to the brain. The brain, sensing this hypermetabolic state, compensates by suppressing energy usage in other parts of the body, resulting in some of the signs of ageing.

England is just about to launch a requirement that institutions protect students from harassment or sexual misconduct by staff members — but PhD students need specific protections, argues scholar and activist Anna Bull. PhDs work more closely with senior researchers than do other students, and can face brutal personal and career consequences if they choose to report an issue. In a toolkit they have developed for university leaders, Bull and her colleague Kelly Prince recommend strategies to prevent grooming, respond proactively to concerns and provide long-term support.

“South Africa is the beacon,” said Nobel-prizewinning cancer researcher Harold Varmus, a former director of the US National Institutes of Health, about the country’s contribution to medical research. Now that beacon is being snuffed out by the loss of significant funding from the United States. “This was American taxpayers’ money and we are incredibly grateful that’s how it was spent, but it wasn’t a gift or a charity,” says HIV researcher Lynn Morris, the deputy vice-chancellor of research and innovation at the University of the Witwatersrand. “These are competitive grants, and the data we produced benefited everyone.”

Today, as temperatures hit 30 oC here in the UK, I’m looking for ways to keep cool. My saviour could be a new, cement-based paint, which ‘sweats’ heat away. The porous paint can absorb water and release heat as the liquid evaporates, which can cool the surface in the same way that sweating cools our skin.

Unfortunately for me, the paint is still hot off the scientific presses, so I might struggle to get my hands on it. I guess I’ll just turn my fan up a notch.

Send your best tips on staying cool, or any feedback on this newsletter, to [email protected].

Thanks for reading,

Jacob Smith, associate editor, Nature Briefing

With contributions by Flora Graham

• Nature Briefing: Careers — insights, advice and award-winning journalism to help you optimize your working life

• Nature Briefing: Microbiology — the most abundant living entities on our planet — microorganisms — and the role they play in health, the environment and food systems

• Nature Briefing: Anthropocene — climate change, biodiversity, sustainability and geoengineering

• Nature Briefing: AI & Robotics — 100% written by humans, of course

• Nature Briefing: Cancer — a weekly newsletter written with cancer researchers in mind

• Nature Briefing: Translational Research — covers biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma