Many of Alex Kachkine’s earliest memories revolve around two core passions. One is engineering. Kachkine’s great-grandfather built bridges, their grandmother developed autopiloting systems for Soviet fighter jets, and their parents have engineering degrees. Kachkine spent their childhood building things. Following in the family’s footsteps, they say, was a foregone conclusion. The other passion — a lifelong interest in art — came about by chance. While on a childhood school trip to the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio, Texas, a tour guide showed the students a seascape by the French Impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir. The subject is hard to visualize close up; only by stepping back does the image fully resolve.

Read the paper: Physical restoration of a painting with a digitally constructed mask

“That was so intriguing to me that I ditched the group, and they had to come find me later,” Kachkine recalls. “I went back to that room and kept walking back and forth in front of this little Renoir piece. From that point on, it just became apparent that I really cared about art.”

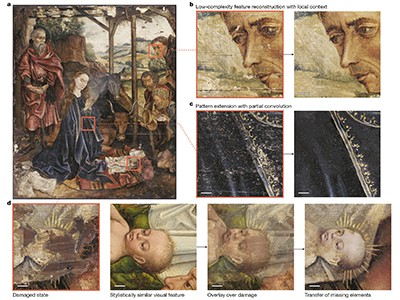

Today, these two preoccupations continue to be drivers in Kachkine’s life, spanning both their career as a graduate researcher in mechanical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge and their extracurricular activities. Kachkine has become an avid art collector and recently developed a restoration method in which they use digital tools to create a ‘mask’ of pigments that can be printed and varnished onto damaged paintings (see ‘Adoration restoration’). The method, detailed in a study published in Nature, reduces both the cost and time associated with art restoration and could one day give new life to many of the paintings held in institutional collections — perhaps as many as 70% — that remain hidden from public view owing to damage (A. Kachkine Nature 642, 343–350; 2025).

The obvious path

Kachkine’s early interest in engineering found a ready outlet in high school, at which they spent their final two years in an accelerated biotechnology course run through Austin Community College in Texas.

Joseph Oleniczak, one of the instructors, began working with Kachkine around 2016, and was immediately struck by their talent. As well as teaching, Oleniczak co-founded a company called Fabrico Technology, also in Austin, to help academics to commercialize their intellectual property. When Kachkine began duel undergraduate degrees in mechanical engineering and economics at the University of Texas at Austin in 2018, Oleniczak hired them to create the hardware and software for a bacterium-detection assay being developed by researchers at the university.

Digitally constructed mask brings a damaged painting back to life

“Of all of the students that I’ve had — and I’ve had some phenomenal ones — Alex is the only one we’ve ever brought on,” Oleniczak says. Fabrico eventually licensed Kachkine’s inventions back to them so that they could start their own company, GeneTiger, that same year. Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Kachkine received a grant from the US National Science Foundation to develop a SARS-CoV-2 detection assay, which the University of Texas at Austin used to screen employees on campus.

“It wasn’t really diagnostic, but if there was a positive, we could encourage people to go get a proper PCR test,” Kachkine says. “I remember the first day we got a real positive. I’d never had that moment of an invention of mine actually being relevant to someone.”

After graduation, Kachkine started looking for jobs but found that many positions required a graduate degree. That’s how, in 2021, Kachkine joined the laboratory of Luis Fernando Velásquez-García, a microsystems engineer at MIT. Like Kachkine, Velásquez-García’s research group defies easy classification, bridging engineering with fields such as aeronautics, astronautics, satellite technology and nanotechnology, and mass spectrometry.

“The lab is not affiliated with any particular part of the university, and we really are our own distinct thing,” Velásquez-García says, adding that when he first came across Kachkine’s application, he thought that their core competence in hard science and entrepreneurial mindset would gel well with the group. “That’s great for where we work, because we create things that often don’t exist yet.”

As a child, Kachkine was captivated by art.Credit: Alex Kachkine

Kachkine’s thesis work tackled a long-standing challenge: developing and optimizing ion sources in mass spectrometry. All mass spectrometers include a device for converting the sample material into a stream of charged particles that the machine can analyse. As they dove into the technology, Kachkine realized what a big role evaporation has in the efficiency of mass spectrometers — “we’re working with microlitre-scale liquids that disappear in seconds,” they explain — yet how little other researchers account for that fact when designing and optimizing their own equipment. “It turns out evaporation is freaking complicated,” Kachkine says. When they looked at the papers that had been published over the past decade that highlight improvements in efficiency, many of the unexpected results they found could be explained by evaporation.

Velásquez-García says that this work, which ultimately allowed the lab to create better, more-efficient devices (A. Kachkine and L. F. Velásquez-García in 21st Int. Conf. Micro and Nanotechnology for Power Generation and Energy Conversion Applications 38–41; IEEE, 2022) exemplifies Kachkine as a scientist: understated, but methodical and dedicated. “If there’s something [they want] to figure out, even if it’s complicated, [they] will spend the time,” Velásquez-García says.

Breathing life back into art

In their spare time, Kachkine continued to purchase and restore art, ultimately amassing dozens of works spanning multiple genres, from abstract expressionism to modernism. “Many people put their money into savings accounts, and I put money into art,” Kachkine says. “As someone with a degree in economics, I should probably know better, but they bring me a lot of joy.”

But to afford their hobby on a student’s budget, Kachkine has had to purchase damaged pieces. A few years ago, they bought a late fifteenth century painting known as the Adoration after Martin Schongauer, attributed to an unknown artist, that required significant restoration.

Meet the MIT engineer who invented an AI-powered way to restore art