International waters, also known as the high seas, make up 61% of the ocean and cover 43% of Earth’s surface — amounting to two-thirds of the biosphere by volume. They have been exploited since the seventeenth century for whales, and from the mid-twentieth century for fish, sharks and squid, depleting wildlife. Now, climate change is reducing the productivity of the high seas through warming and through depletion of nutrients and oxygen. Proposals to fish for species at greater depths and mine the sea bed threaten to wreak yet more damage, putting the ocean’s crucial role in maintaining the stability of Earth’s biosphere at risk.

Less than 1% of the area of the high seas is protected, however. This is because there has been no globally accepted mechanism to do so beyond Antarctica. The United Nations High Seas Treaty was agreed in 2023 to fill this governance gap and expand the number of marine protected areas in international waters. It is crucial to protect at least 30% of the world’s oceans by 2030, as agreed under the Global Biodiversity Framework in 2022.

To save the high seas, plan for climate change

But the High Seas Treaty could take years to come into force. Sixty countries are required to ratify it; as this article was published, only 28 had done so. Processes and mechanisms are yet to be set up. And its implementation is likely to be hampered by a lack of data, disagreements about divisions of responsibilities and the perennial problems associated with multilateralism.

Given the urgency of addressing the climate and biodiversity crises, the world can’t wait another decade to fix the problems humans have created. Ocean life is too precious and important to lose, and shifts in the chemical and physical environments of the sea, once made, will be irreversible on timescales of centuries to millennia.

As world ocean specialists and policymakers convene this week at the UN Ocean Conference in Nice, France, we make a case for permanent protection of all international ocean waters from fishing, sea-bed mining, and oil and gas exploitation.

Oceans store carbon and nutrients

The high seas are home to an immense diversity of wildlife, including megafauna, such as cetaceans, turtles, tuna and sharks that migrate over vast distances. They also play a crucial part in Earth’s carbon cycle, which is essential for life and the balance of gases in the atmosphere. Indeed, with an average depth of 4,100 metres, the high seas are the planet’s largest and most secure carbon sink.

The crucial role of marine life in the high seas influences the global carbon cycle through two mechanisms: the biological pump and the nutrient pump. In the biological pump, fish and invertebrates living in the twilight ‘mesopelagic’ zone (at depths of 200–1,000 metres) comprise billions of tonnes of biomass and undertake daily vertical migrations, feeding by night near the surface and returning by day to the deep, where they deposit carbon-rich faeces. Without this cycle, atmospheric carbon dioxide levels could be 200 parts per million higher, and Earth possibly 3 °C warmer, than under pre-industrial conditions1.

The nutrient pump is important because dead plants, animals and their faeces sink from shallower to deeper layers of the ocean. Much of the high seas experiences limited mixing — warmer surface waters float on top of colder, denser and darker water — so marine life in the sunlit upper 200 metres is limited by low nutrients. Marine megafauna, such as bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus), sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) and leatherback turtles (Dermochelys coriacea), dive deep to feed and return to the surface to breathe, thermoregulate or digest their prey. Faeces and urine produced near the surface transfer nutrients from deep to shallow water, boosting production of biomass, which takes up dissolved CO22.

Krill fishing in the Southern Ocean.Credit: Associated Press/Alamy

This upward nutrient pump has been slowed by centuries of intensive exploitation, beginning with the whaling industry, which resulted in the collapse of cetacean populations across the entire ocean by the mid-twentieth century. Fishing of the high seas came later, beginning with Japanese long-distance tuna fisheries in the 1930s, expanding to longline fishing for billfish (Istiophoridae) and sharks in the 1950s, deep-sea bottom trawling of seamounts and continental slopes from the 1960s and 1970s, and squid ‘jigging’ (using lights to attract squid) from the 1990s.

Five priorities for a sustainable ocean economy

Encouraged by government subsidies3, fishing in the high seas has intensified — involving an estimated 3,500 boats in 20184. This has depleted many fished species and caused serious collateral damage to wildlife and habitats, driving iconic and vulnerable species, such as some albatrosses (Diomedeidae), oceanic whitetip sharks (Carcharhinus longimanus) and leatherback turtles, to become critically endangered.

Pressure is now mounting to fish at greater depths, despite very limited understanding of the structure and function of deep-sea ecosystems. Although mesopelagic species are mostly small and unsuitable for direct human consumption, government- and industry-sponsored researchers are looking for new sources of fishmeal and oil to supply the burgeoning aquaculture industry.

Expansion of fisheries to deeper waters could reduce the amount of carbon that the oceans take up and deplete a key source of food for species such as tuna, sharks and dolphins. For these reasons, conservationists have argued for a moratorium on fishing in the mesopelagic zone5, helping to safeguard the estimated 59% of ocean carbon sequestration that happens in the high seas6.

No need to fish in the high seas

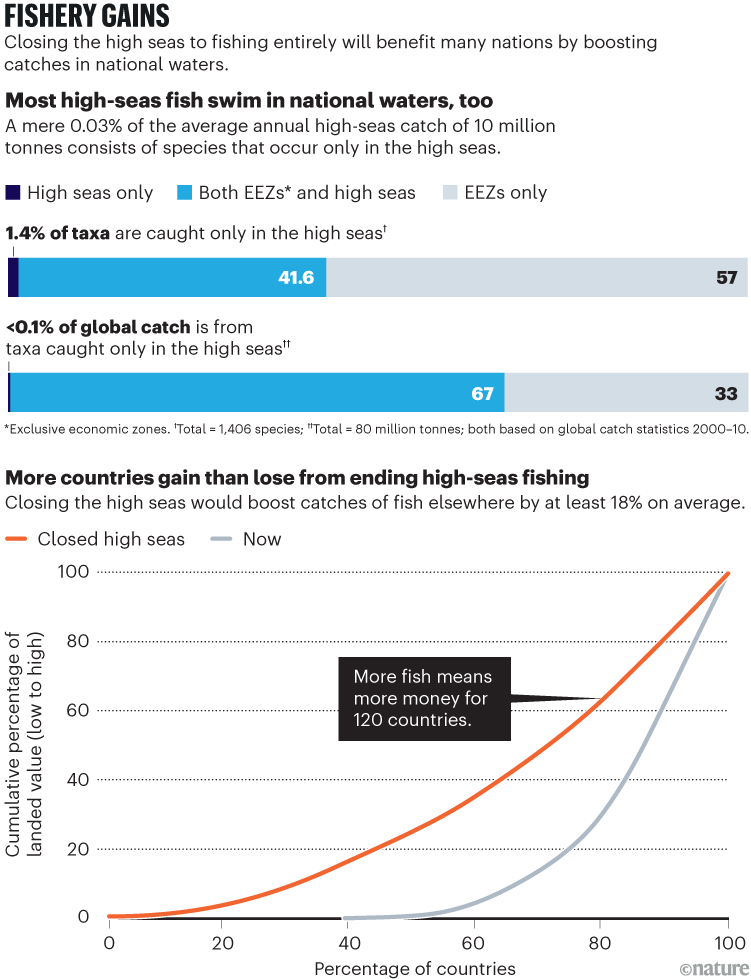

High-seas fisheries occur from the poles (for species such as krill, cod, Antarctic icefish and toothfish) to the tropics (for tuna, billfish, sharks and opah, for example). The devastating and poorly managed impacts of fishing were among the main motivations for the High Seas Treaty (formally known as the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction Agreement). Closing the high seas to fishing has been proposed before by academics7,8 and by a high-level panel made up of former heads of state, government ministers and policy experts9. There are compelling reasons to do so (see ‘Fishery gains’).

Source: Ref. 8

High-seas catches and profits are constrained by the sparseness of biomass in these remote regions10. This means that little of the global fish catch (less than 6%) comes from the high seas3, and most of this is destined for consumption in the high-income world. Food-security arguments, therefore, do not apply. Few countries have the capital to invest in high-seas fishing. Around 80% of the high-seas catch is landed by only six regions: the Chinese mainland, Taiwan, Japan, Indonesia, Spain and South Korea3.

Many of these fisheries are economically viable only because they are propped up by government subsidies. High-seas fishing generated profits of between US$3.8 billion and $5.6 billion in 2014, but with subsidies of $4.2 billion3. Costs are further ‘subsidized’ by low wages, and sometimes by forced or slave labour, with human-rights abuses prevalent.

Guess how much of the ocean floor humans have explored

Not fishing these remote waters would save taxpayer money and prevent publicly funded declines in endangered, threatened and protected species, as well as immense damage to the sea bed and open-water habitats. High-seas species are currently fished using destructive and polluting methods, with limited oversight, little enforcement and weak governance under international law by regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs).

By-catch, by-kill and pollution problems are often extreme. Each year, pelagic longline fisheries kill hundreds of thousands of seabirds, thousands of turtles and millions of high-seas sharks.

In the 1990s, in addition to pursuing free-swimming tuna schools, ‘purse seine’ fisheries adopted satellite-tracked drifting fish aggregation devices (dFADs), which are rafts with a net or rope structure hanging beneath. As well as tuna (mostly juveniles), the large wall of netting collects other wildlife, such as turtles, dolphins, whale sharks and manta rays, which are often killed.

Between 2007 and 2021, upwards of 120,000 dFADs were deployed annually and drifted across 37% of the ocean11. Depending on the fishery, up to 90% of dFADs are lost or abandoned at sea12. Many RFMOs have taken steps to regulate their use, but the regulations are insufficient and poorly enforced12.

Frozen tuna for sale at a fish market in Tokyo.Credit: Kazuhiro Nogi/AFP via Getty

The sustainability of high-seas fishing is being placed at further risk by deoxygenation from warming and stratification. The global ocean has lost around 2% of its oxygen content over the past 50–60 years13. Deep-water deoxygenation is reducing the habitat volume for oxygen-demanding species, such as sharks and tuna, pushing them closer to the surface, where they are more easily caught. Lower levels of dissolved oxygen also lead to slower growth and smaller body size, reducing productivity and reproduction14 — effects that will be amplified by interactions between fisheries, deep-sea mining, climate change and habitat destruction.

Closing the high seas to fishing would support population recoveries of targeted species7. Fishers would have access to healthier, more productive stocks that spill into national waters, where they could be exploited with better governance and oversight — 98.6% of exploited high-seas fish straddle national waters8. Remote regions such as the high seas, when highly protected, generate greater conservation benefits for ocean wildlife relative to areas that are closer to humans15.

Fishing in national waters would be more equitable, expanding beneficiaries to include most fishing nations, many of them low- and middle-income countries. Sustainable catch volumes are potentially greater than present high-seas catches8. And population recoveries of ocean-going megafauna would help to compensate for deoxygenation-driven declines in productivity, as well as boosting the upward nutrient pump.