It was the finger seen around the world.

In 2008, archaeologists working in Denisova Cave in southern Siberia, Russia, uncovered a tiny bone: the tip of the little finger of an ancient human that lived there tens of thousands of years ago.

The fragment didn’t seem remarkable, but it was well preserved, giving researchers hope that it harboured intact DNA. A team of geneticists led by Johannes Krause at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, removed 30 milligrams of bone and managed to extract enough intact DNA to analyse it. They were able to sequence the entire mitochondrial genome — and were shocked by what they found. The DNA did not match that of modern humans, or of Neanderthals, the other likely candidate1. It was a new population, which they dubbed the Denisovans, after the cave.

How Denisovans thrived on top of the world: mysterious ancient humans’ survival secrets revealed

When the team announced this result in March 2010, it caused a sensation. Up to that point, researchers had used preserved bones to identify every species or population of hominin — the group that includes modern and ancient humans and their immediate ancestors. “Denisovans were created from DNA work,” says palaeoanthropologist Chris Stringer at the Natural History Museum in London.

Nine months later came the second bombshell. Krause and his colleagues had obtained the entire nuclear genome from the finger bone, which yielded much more information. It showed that the Denisovans were a sister group to the Neanderthals, which lived in Europe and western Asia for hundreds of thousands of years. The team also described the discovery of a molar tooth, which, on the basis of its mitochondrial DNA, was Denisovan: it was unusually large, unlike teeth from modern humans or Neanderthals.

A replica of an ancient finger bone found in Denisova Cave. DNA extracted from this bone was used to first identify the Denisovan lineage.Credit: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

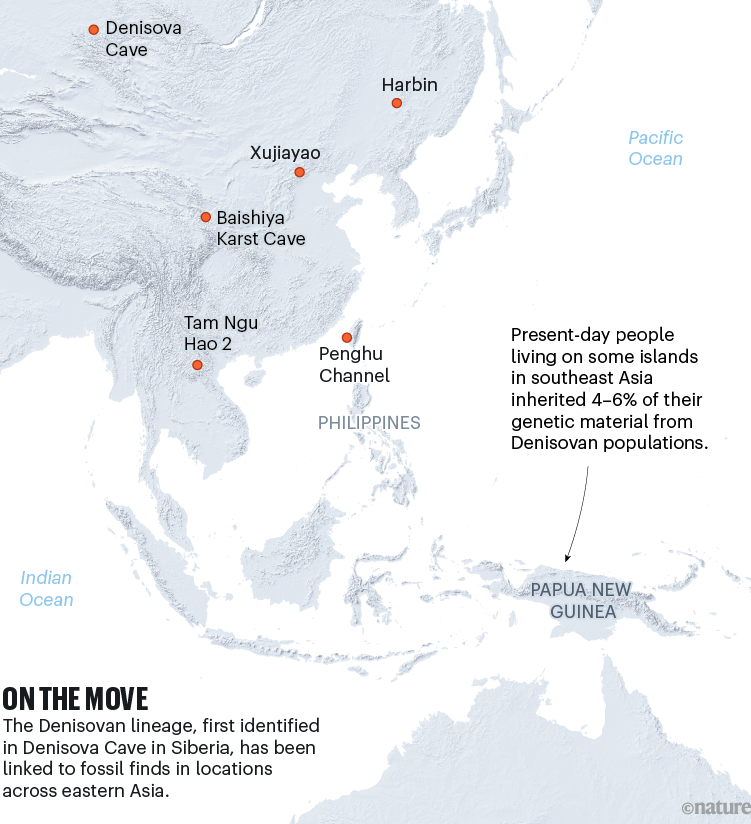

Even more surprisingly, the team reported that present-day people living on the islands of New Guinea and Bougainville in the southwestern Pacific Ocean have inherited 4–6% of their DNA from Denisovans, despite the fact that these islands are roughly 8,500 kilometres from Denisova Cave. This implied that modern humans interbred with Denisovans, and that Denisovans were once widespread across Asia2.

That finding triggered a frantic search for the Denisovans. If they had ranged as far as it seemed, where were the fossils? Had palaeoanthropologists not yet found them, or were they sitting unrecognized in museum collections? Researchers went back to the field and explored dusty museum drawers to try to uncover clues about this mysterious group of ancient humans.

Now, 15 years after the first report on this hominin, a handful of fossils have been identified as Denisovan, with varying degrees of certainty. Some are from the lofty heights of the Tibetan plateau; one was hidden in a well for decades; another was dredged from the bottom of the sea. They reveal a diverse, adaptable population that lived in frigid Siberia, at high altitudes and in the tropics — and researchers are scouring Asia for more evidence of them. What they have found so far could force a rethink of the origin of our species.

The invisible people

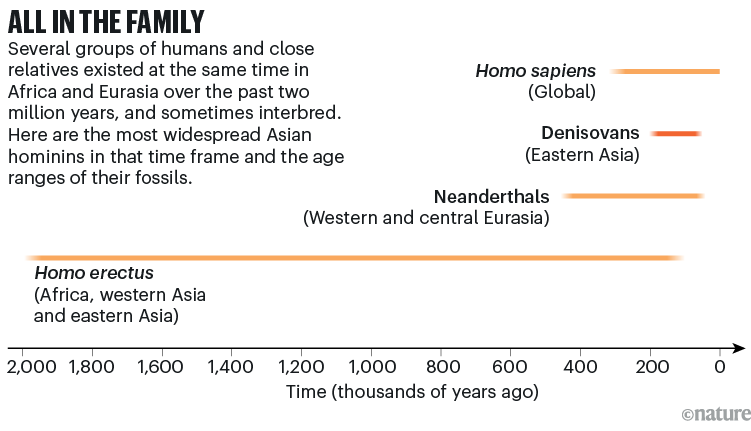

The story of hominins starts in Africa, where the oldest known species all lived. The earliest one found outside of Africa was Homo erectus, which inhabited what is now Georgia 1.8 million years ago and soon spread as far east as the island of Java in Indonesia3. Later came the Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis), which dispersed throughout Europe and western Asia, sometimes venturing as far as Denisova Cave. At the same time, the Denisovans were living in eastern Asia.

Our own species, Homo sapiens, was the last to evolve, appearing at least 200,000 years ago in Africa (see ‘All in the family’). One fossil find in Morocco suggests that modern humans might date back more than 300,000 years4. H. sapiens left that continent in several waves, eventually replacing all other hominins. But before they did, some of them mated with Neanderthals and Denisovans. Today, the highest levels of Denisovan DNA are found in the Ayta people of the Philippines, but Denisovan DNA is widespread in people from southeast Asia, including Papua New Guinea5.

Sources: H. erectus: A. I. R. Herries et al. Science 368, eaaw7293 (2020)/Ref. 3; Neanderthals: C. Stringer Curr. Biol. 35, R29–R31 (2025); Denisovans: S. Brown et al. Nature Ecol. Evol. 6, 28–35 (2022)/H. Xia et al. Nature 632, 108–113 (2024); H. sapiens: Nature https://doi.org/PM44 (2017).

When researchers set out to find Denisovan fossils, they discovered that one had been collected decades before — and had gone unrecognized.

“The fossil was found without context by a Buddhist monk,” says archaeological scientist Katerina Douka at the University of Vienna. In 1980, the monk had found a lower jawbone in Baishiya Karst Cave on the Tibetan plateau in China. For three decades “it sat in someone’s office”, says Douka, until it came to the attention of researchers, including geographer Fahu Chen at the Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, in Beijing. In a 2019 study, Chen and his colleagues extracted and analysed preserved proteins that identified the bone as Denisovan, and dated it to at least 160,000 years ago by measuring radioactive decay in the sediment stuck to the bone’s surface6.

Researchers collect sediment samples from Baishiya Karst Cave on the Tibetan plateau in China, where Denisovan bones and DNA have been found.Credit: Han Yuanyuan

The following year, many of the same team reported finding Denisovan DNA preserved in the sediments of Baishiya Karst Cave. This indicated that Denisovans were present there around 100,000 and 60,000 years ago, and that they might have stuck around until 45,000 years ago7. These two studies established that Denisovans lived successfully on the high-altitude Tibetan plateau. This fits with a 2014 genetic study, which found that modern Tibetans have inherited a Denisovan genetic variant that helps them to cope with low oxygen levels, presumably from ancient interbreeding between modern humans and Denisovans in that region8.

In parallel, another dramatic fossil find emerged more than 2,000 kilometres away, in northeast China: it looked like it might be a Denisovan, but the controversy over its classification has rumbled on ever since.

The secret skull

It started in the 1930s, in Harbin, China. An unidentified Chinese man, working for the Japanese forces who occupied that region of China at the time, discovered a hominin skull, recognized its value and hid it down a well. He kept it secret for decades, only revealing its location on his deathbed. His family recovered it in 2018 and donated it to a museum.

Siberia’s ancient ghost clan starts to surrender its secrets

A team led by palaeoanthropologist Xijun Ni at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing — and including Stringer — described the Harbin skull in 2021. They found it was at least 146,000 years old. The skull is large, with a cranial capacity comparable with that of modern humans. However, its shape does not match any described hominin species9. In a separate paper, Ni and others described this specimen as belonging to a new species: Homo longi (Dragon Man)10.

Several features of the Harbin skull, notably its big molar teeth, seemed like they might be a match for Denisovans. The same was true of a lone molar tooth found in 2018 at Tam Ngu Hao in the northern mountains of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic11. Protein analysis confirmed that the tooth was from a member of the genus Homo, but could not confirm the species. However, its shape resembled the molars from Baishiya Karst Cave, so the discoverers pegged it as a Denisovan. The fossil possibilities were starting to mount up.

Some researchers propose that this fossilized skull found in Harbin City in northeast China belonged to a Denisovan.Credit: Q. Ji et al./Innovation

Meanwhile, other researchers had been re-examining fossils excavated years earlier, such as a set of skull fragments discovered in the 1970s in Xujiayao, northeast China. Their classification has remained contentious. About ten years ago, anthropologist Christopher Bae at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa saw a photo of a Xujiayao molar side by side with a photo of a molar from Denisova Cave. “They were almost exactly the same,” he says.

Protein analysis of a mandible found off the coast of Taiwan indicates that it is Denisovan.Credit: Jay Chang

One more possible Denisovan sample had turned up in 2008, before the group was even identified. Early that year, a man bought a lower jawbone from an antique shop in Tainan City in Taiwan. It had been dredged from the Penghu Channel, 20 kilometres offshore. The man donated it to a museum after researchers realized, on the basis of photographs, that it was a hominin bone. When they finally described it in 2015, the researchers noted that its second molar looked distinctly Denisovan12. This was supported by a study published this April, in which proteins extracted from the fossil indicated that it belonged to a male Denisovan that lived sometime between 10,000 and 190,000 years ago13 (see ‘On the move’).

Source: Ref. 13

A messy family tree

In a preprint first published last May, Stringer and his colleagues tried to bring all these disparate fossils together. The problem they faced was vexing: there are a great many unclassified Homo fossils from eastern Asia, and it’s not obvious how many groups they represent.

The team analysed 57 hominin fossils, examining up to 521 characteristics of each, depending on how much material was available. This allowed them to reconstruct a family tree showing which fossils belonged to the same groups.

The Eurasian hominins clustered into three groups: modern humans, Neanderthals and H. longi. That third group included the original Denisova remains and the Baishiya Karst Denisovans, as well as the skull fragments from Xujiayao, the specimen dredged from the Penghu Channel and several other Chinese fossils14.

“We would say that the name for Denisovans is going to be longi, if there is a species name,” says Stringer.