May 17, 2025

Although the reparations bill was just one of 23 vetoes issued by Moore, it sparked a firestorm of criticism from fellow Black leaders across the state.

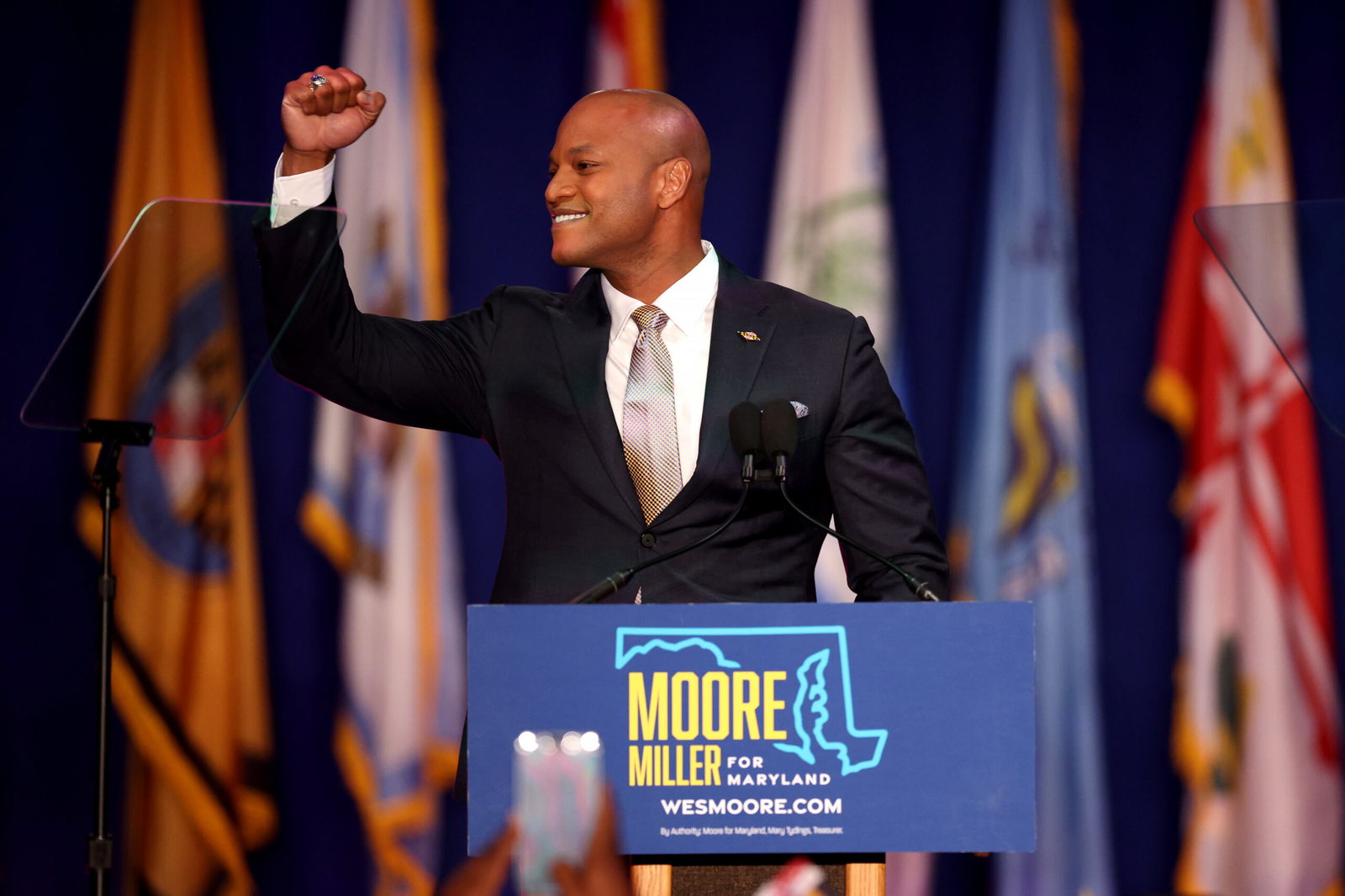

Wes Moore, the nation’s only Black governor and a Democrat, vetoed a bill in the late hours on May 16 that would have created a commission to explore reparations for Black Marylanders and formally recognize the economic harm inflicted on descendants of enslaved people in the state.

According to The Washington Post, while the bill was one among 23 vetoes issued by Moore, it ignited a firestorm of criticism of Moore’s decision from other Black leaders in the state who had counted on Moore to be an ally in their fight for reparations, given his stance on repairing the racial wealth gap, which itself stems from the enslavement of Black people.

Moore, however, defended his decision by saying, among other things, that he needed to keep an eye on the budget and that he didn’t want to wait two years to set up a commission to study reparations.

“I was very transparent with the leadership and members of the General Assembly that anything that fails to meet the urgency of this moment, I will not sign it and it must wait for another time,” Moore told the Post in an interview, before saying that his decision regarding the reparations study was “the most challenging” of his vetoes.

Moore continued, “A study group that is saying that they’re going to present reports to the governor in two years is fine. But the governor is ready to engage now.”

Sen. Anthony Muse, a Democrat who previously led a rally outside the governor’s residence in Annapolis that pressured Moore to sign the bill, characterized the reaction to the governor’s actions not just in Maryland, but nationwide, as a kind of betrayal.

“Everyone is upset about this,” Muse told the outlet ahead of Moore’s veto, “There will be a real backlash from the Black community — not just in Maryland, nationwide. I’ve had two conversations with him about it, we all walk away from it the same way: ‘What in the world?’

Immediately after Gov. Moore’s veto, the Maryland Black Caucus, which counts Rep. Muse as a member, issued a statement that indicated that the bill was veto-proof and that the legislative branch had the final say on the bill, not the governor.

“The State’s first Black governor chose to block this historic legislation that would have moved the state toward directly repairing the harm of enslavement,” the caucus stated. “While unilateral executive actions and piecemeal legislation addressing disparities can contribute to progress, they cannot substitute meaningful, sustained, and comprehensive efforts.”

Despite their disappointment with Moore’s decision, reparations advocates are split on Moore’s choice to veto a commission. Some, like Nkechi Taifa of the national organization, the Reparation Education Project, argued that Gov. Moore should have stood behind the establishment of the task force ahead of the veto.

“For him not to do this would really be a slap in the face to the momentum of the movement. He must not be cowered by the current politics of the issue. Why not establish just a task force? It’s just a study and a commission to recommend amends. What is wrong with that?” Taifa asked in her comments to the Washington Post.

Others, like Maryland Sen. Ron Watson, a Democrat, believe that the study of reparations does nothing to advance the fight for Black people to gain generational wealth. Without directly calling it such, Watson seems to believe that the debate over studying reparations is a distraction from other goals.

“We know about housing redlining, we know about missed educational opportunities, we know about food deserts,” Sen. Watson (D-Prince George’s) told the Post. “We need to move forward.…The reparations study does nothing to promote generational wealth.”

Notably, Sandy A. Darity, arguably the nation’s foremost voice on reparations, continued his argument that a state-level reparations package would essentially come back marked insufficient funds to cover the financial redress due Black people regarding slavery because it was a national project, not just the purview of a few states.

“The problem here is the sheer inability of a state government to execute a comprehensive program of reparations for Black descendants of U.S. slavery,” Darity told the Post via email.

Darity continued, “We should not take a fragment of a loaf or even half of a loaf in the form of something labeled ‘reparations’ when it falls short of what is due. And, intrinsically, state and municipal efforts will fall short of what is due.”

RELATED CONTENT: Summer Lee Keeps Conversation on Reparations Alive By Reintroducing Legislation