You have full access to this article via your institution.

Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

Researchers have identified a genetic dial in the human brain that, when inserted in mice, boosts their brain size by about 6.5%.Credit: Sergey Bezgodov/Shutterstock

Inserting a snippet of genetic code unique to humans into mice helps the animals grow bigger brains than usual. The stretch of DNA, called HARE5, acts like a dial to turn up the expression of certain genes, expanding the outer layer of the mouse brain by increasing the production of cells that become neurons. The finding could help to explain how humans evolved such large brains compared with their primate relatives.

Google DeepMind researchers say that they have created an artificial intelligence (AI) system that can find solutions to major problems in mathematics and computer science. AlphaEvolve — which has not been rolled out beyond the company — combines large language models with algorithms that can scrutinize the model’s suggestions to filter and improve solutions. AlphaEvolve has helped to improve the design of the company’s next generation of chips, developed specially for AI computations, and has found a way to more efficiently exploit Google’s worldwide computing capacity, says DeepMind’s head of science Pushmeet Kohli.

Reference: Google DeepMind white paper

Fossil claw prints found in Australia were probably made by the earliest known amniotes — the group that includes reptiles, birds and mammals. The findings push the origin of this group back to around 35 million years earlier than was previously thought. There are no marks of dragging bellies or tails, which could hint that the animals were able to hold their bodies up while they walked — an indicator that they had evolved for complex movement. Or they might have been ‘punting’ in shallow water, says palaeontologist Steven Salisbury.

A four-legged animal similar in appearance to modern-day salamanders is thought to have left these imprints found on a sandstock block.

Features & opinion

To study the brain, neuroscientists have long used clusters of tissue known as organoids. Grown in the right cocktail of chemicals, these models can mimic specific brain regions such as the thalamus, where sensory information is processed. By fusing multiple organoids into structures called ‘assembloids’, scientists can create miniature neural networks to study interactions across the organ. Now, a suite of new technologies is helping to create more-tailored assembloids that recreate specific aspects of brain mechanics. But the brain is not a Lego set, and more ‘realistic’ models can complicate efforts to scale and reproduce neuroscience research.

Cognitive neuroscientist Karen Arellano had success starting conversations on the dating app Tinder — until she brought up her PhD. Her luck changed when she met physicist Jon D’Emidio, a fellow researcher who understood the demands of grad school. “It was the first time I felt that someone knew the struggles I was talking about,” she says. Finding a long-term partner can be difficult for early-career researchers who struggle to find time to meet people while juggling a gruelling workload. But developing meaningful relationships is good for both your mental health and career. “Taking time to develop strong connections needs to be prioritized,” says cognitive scientist Laurie Santos.

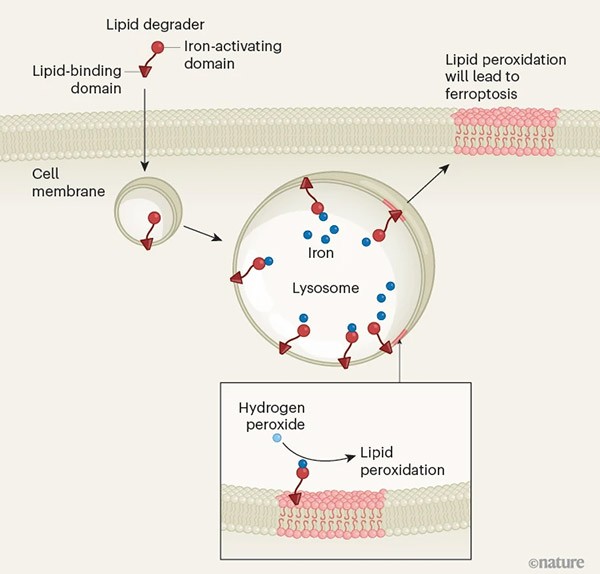

Infographic of the week

A lipid-degrading small molecule could kill treatment-resistant cancer cells by exploiting the cells’ high iron content. Iron boosts cancer growth, so tumour cells hoard it in cellular pockets called lysosomes. Researchers have designed a molecule that can bind to lipids — the molecules that make up the membranes around cells and lysosomes — and chemically activate iron. Inside a lysosome, the molecule triggers a process called lipid peroxidation, aided by hydrogen peroxide. The lysosome ruptures and releases iron into the cell, which kills the cell through a process called ferroptosis. (Nature News & Views | 6 min read)

Today I’m checking all of the artwork in my house, just in case I’ve accidentally got hold of a priceless original.

It might seem unlikely, but it’s happened before. Harvard Law School paid US$27.50 for a ‘copy’ of the Magna Carta in 1946. Now, academics believe it’s a genuine article, which makes it one of the most valuable documents on the planet.

Your feedback on this newsletter is extremely valuable to us. Please send any that you might have to [email protected].

Thanks for reading,

Jacob Smith, associate editor, Nature Briefing

With contributions by Flora Graham and Gemma Conroy

Want more? Sign up to our other free Nature Briefing newsletters:

• Nature Briefing: Careers — insights, advice and award-winning journalism to help you optimize your working life

• Nature Briefing: Microbiology — the most abundant living entities on our planet — microorganisms — and the role they play in health, the environment and food systems

• Nature Briefing: Anthropocene — climate change, biodiversity, sustainability and geoengineering

• Nature Briefing: AI & Robotics — 100% written by humans, of course

• Nature Briefing: Cancer — a weekly newsletter written with cancer researchers in mind

• Nature Briefing: Translational Research — covers biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma