Papers must often wait in a long queue to be handled by editors and sent out for review.Credit: Martin Poole/Getty

I am a conservation scientist working at the National Institute for Environmental Studies in Tsukuba, Japan, where I focus on human impacts on wildlife. I’d like to find a tenure-track position at a university, and I’ve applied to institutions in Japan and Taiwan, where I earned my PhD.

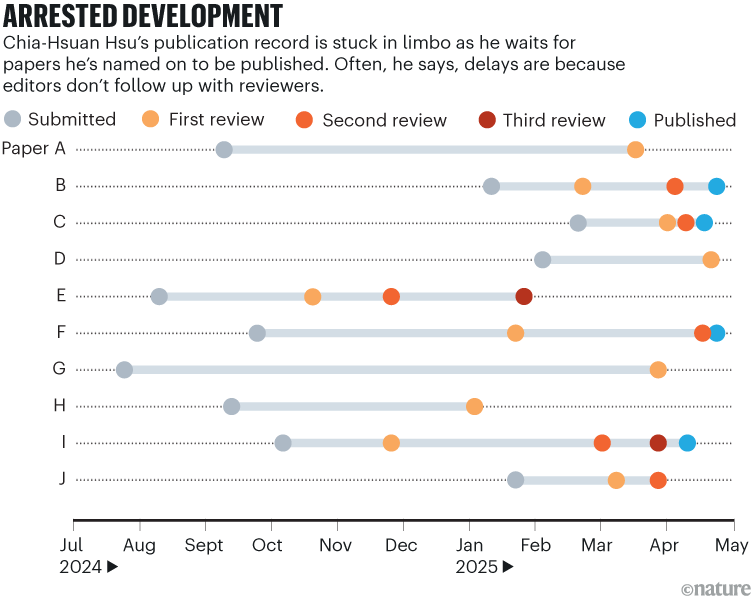

But I’ve encountered challenges in the job-application process, particularly regarding publications. Chief among them are huge delays in the review process for ten papers that I’ve worked on, which have affected what I can officially list on my CV (see ‘Arrested development’).

In East Asian academia, your publishing history remains the main measure of success — and is perhaps even more important for career advancement than it is in other places. Worldwide, by contrast, there is a move away from evaluating scientists purely on metrics and published papers, which should be welcomed.

Sticky system

Building a publishing history requires investing substantial time and effort in conducting experiments, analyses and writing — all processes that researchers can largely control. But after submission, a paper’s progress is no longer in the author’s hands. Delays in the review process can affect job applications, funding opportunities and eventually researchers’ entire careers, particularly those of early-career scientists.

The futures of researchers’ careers are, in many ways, controlled by others — mainly journal editors and reviewers. Of course, the process involves many stages: checks by managing editors, screening, finding peer reviewers, facilitating and conducting peer review, editorial decisions, manuscript revisions and more. If a paper gets stuck at any stage of this process, a researcher’s career progress might be stuck with it.

Editors play a crucial part in this process, because they have the power to accelerate it. Most editors send out peer-review invitations promptly, follow up with reminders, make timely rejection decisions and keep authors updated on article progress. I’m hugely grateful for them: they help save researchers valuable time.

Waiting in the wings

One of my own manuscripts was under review for more than a year. As an early-career researcher, I hesitated to follow up with the editor, fearing that I might leave a negative impression. In hindsight, I should have reached out much earlier. After waiting a year and six months after submission, I finally sent a polite inquiry. The editor responded, one day later, to let me know the delay was due to difficulties in finding suitable reviewers.

They also told me that of the three reviewers they contacted, two never responded and a third agreed to write a review that never manifested. In a year and a half, the editor had contacted only three possible reviewers — and failed to follow up with any of them.