At one of Germany’s top-funded universities, a high-profile biology researcher has bullied his large group of junior staff, targeting women and international students, for decades. In interviews with Nature’s careers team, 14 current and former laboratory members detail what they describe as endless demands for unrealistic levels of research productivity. If those demands aren’t met, they allege, he withholds letters of recommendation and approval of time off work. If displeased, he denies funding or sends disparaging e-mails to researchers’ potential employers. Verbal abuse is commonplace. Women report being warned not to get pregnant while a member of his lab.

The university is aware of his behaviour. Yet, no investigation has been conducted nor any sanctions imposed because the complainants requested anonymity, fearing retribution — anonymity that cannot be upheld in an investigation owing to German labour law. This, along with defamation and other laws in Germany, can make it difficult to report on these incidents or to impose sanctions against professors, most of whom are tenured civil servants.

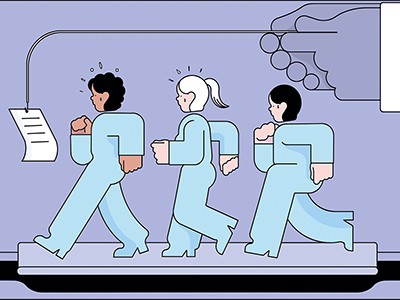

Shrouded in secrecy: how science is harmed by the bullying and harassment rumour mill

Germany is not the only country to have a problem with bullying in academia, but a combination of structural and legal powers that, in effect, protect tenured professors over early-career researchers, enables and emboldens abusers. “It’s considered culturally normal — this is just what science is like,” says Daniel Leising, a psychology researcher and professor at the Technical University of Dresden in Germany. Several people interviewed by Nature’s careers team, including Leising, use ‘king’ to describe professors, meaning they are untouchable. “There is far too much power in the hands of professors in the German system,” he says.

“It’s not everybody,” stresses intervention psychologist Andrea Kübler, who is dean of the faculty of human sciences at the University of Würzburg, Germany, noting that those who abuse their power are by far the minority. But those who do so cause a lot of harm, she explains. Kübler is one of more than 100 members of the Network for Sustainable Research, a group formed in April 2024 to identify and advocate for structural reforms to protect junior scientists who don’t have permanent contracts.

Although the details given by the 14 lab members relate to one professor’s case, the pattern of reported behaviour is similar across several cases that have made headlines in Germany in recent years. In 2023, a professor at the University of Göttingen, Germany, lost his job and pension when he was convicted of multiple physical assaults on a Vietnamese doctoral student and on two other female junior members of his group. His offences came to light in 2017, but it took six years and two trials before the university could remove his civil-servant status. In 2023, a German national newspaper reported that a university in western Germany took steps to prevent a female professor from supervising new PhD students after she insulted and exploited around a dozen students.

Leising says that these and other press reports of abuse are crucial, supporting growing calls for structural reforms. Amid increased concern that academic abuse was rampant but under-reported, Leising and his colleagues were asked by the German Psychological Society in 2022 to write a report identifying the factors that give rise to academic power abuse in science in Germany.

Released in June 2023 (an updated English version was published in February this year)1, Leising’s report broadly defined unethical behaviour as encompassing bullying, sexual harassment, scientific misconduct, exploitation and corruption. The authors noted that the academic system in Germany is remarkably hierarchical, steeped in historical deference to professors and further entrenched with a lack of effective oversight. These conditions are particularly conducive to unethical behaviour, owing to the extreme power differential between professors and early-career researchers. This raises fear of retaliation in people who have experienced abuse. Internal complaint channels also tend to be understaffed and have little authority to impose sanctions, says the report.

Daniel Leising co-authored a report exploring the factors that contribute to academic bullying in Germany.Credit: Daniel Leising

Leising’s report and this article focus on universities, but other independent research institutions, including the Max Planck Institutes, are not immune to similar abuse complaints, as has been reported by news outlets, including Nature (see Nature 571, 14–15; 2019).

In Germany, a typical large academic research group is structured with a professor, who has lifelong tenure, at the top. The professor manages and supervises early-career researchers — from graduate and postdoctoral students to junior professors and research-group leaders, the latter being the most independent. It is the professor who assigns a graduate student’s final grade. Almost all doctoral candidates at universities are on short-term contracts, which are dependent on the professor for renewal and last, on average, less than three years. The average time, in 2023, to get a doctorate in Germany was 5.1 years. At the same time, 72% of junior research-group leaders were on fixed-term contracts.

Whatever minimal oversight academic departments have, they rarely exercise it, says Leising. Kübler says: “The strong hierarchy is a problem. And there is no official way for people who suffer from power abuse to know they will receive some help.”

Structural changes are being pursued, but these are modest. At the national level, scientists are lobbying to extend the length of contracts for early-career researchers to four years, which they consider to be the minimum length of time necessary to finish a PhD. And one German state, North Rhine-Westphalia, is attempting to prevent professors from being both a graduate supervisor and a grader. Furthermore, some university departments are restructuring to flatten power dynamics and create more permanent positions. Many countries also have problematic academic hierarchies and will be watching Germany’s progress.

Growing complaints

Although there are no baseline data on the total number of people who have experienced academic power abuse, there are some interesting data points. The 2024 Berlin Science Survey2 found that around 23% of 2,748 respondents in Germany had experienced an abuse of power in the previous 24 months, and roughly 39% had observed it at least once. At the same time, the number of general enquiries has risen at the Ombuds Committee for Research Integrity, which serves all researchers who are affiliated with the German research system. “Our number of enquiries has increased continuously over the last years — from 87 in 2016 to 262 last year,” says Hjördis Czesnick, who heads the office of the committee. Her office doesn’t have any evidence that abuse or misconduct has increased over that time or that it was less in the past; it assumes there is greater awareness that the office exists, says Czesnick.

Underpaid and overworked: researchers abroad fall prey to bullying

In 2021, Jana Lasser, a computational social scientist now at the University of Graz in Austria, co-founded the Network Against Abuse of Power in Science to document cases of academic abuse and support those who have experienced it in Germany. Since then, the network has reviewed roughly 120 cases. Lasser says that the complaints are often similar to those found by Nature for this article, including extortion of labour in exchange for contract renewals, supervisors refusing to let students graduate and bullying and misogynistic behaviour.

Susanne Menzel-Riedl, president of Osnabrück University, Germany, and vice-president of the German Rectors’ Conference, an association of roughly 270 higher-education institutions, sees the reporting of complaints as a positive sign. “The more complaints we see, the better. It points to a process that is open about the problem. This is a sign of quality and not of weakness,” she says. The German Rectors’ Conference has made addressing the abuse of academic power a priority. “Decades ago, it was impossible to talk about,” Menzel-Riedl says.

Leising contends that harassment of all types is widely under-reported. He co-authored a study3 that surveyed thousands of students and employees at Germany’s Technical University of Dresden; only 14% of respondents who identified as targets of physical sexual harassment said that they filed a complaint afterwards. “The biggest problem that we have is the level of fear among victims and witnesses of misconduct,” he says. “Fear of being retaliated against, fear of career sabotage, fear of being ostracized. And all of this fear is justified.”

Leising points out that power-abuse behaviours — including lying, cheating and predation — can be characteristics of ‘functional psychopaths’. “But in German academia, they may find particularly fertile soil to act on their impulses without ever being called out for it, or punished,” says Leising. In fact, he adds, some of them are cheered on by the institutional leadership. The term functional academic psychopath was first outlined in a 2018 study4, which determined that, without strong institutional constraints on such people, bullying behaviours will prevail.

“It is a threat to the integrity of research,” Lasser says. “People are under so much pressure, it creates sloppy science in the best cases, and outright data falsification in the worst case.”

One of the biggest challenges, says Lasser, is that her network can’t do anything more than provide support and help the people who experience abuse to contact the appropriate university grievance channels. “I see people running from one organization to the next, not getting help,” she says.

Computational scientist Jana Lasser co-founded a watchdog and support network for scientists who have experienced academic power abuse.Credit: Timotheus Hell

The Ombuds Committee for Research Integrity, for example, can address complaints only if they are specifically related to research, such as authorship disputes. It can’t address those involving racism, discrimination or sexual abuse. “We don’t have investigative power,” says Czesnick. In such cases, the committee can forward complaints to the institution and suggest an investigation, but “has no legal mandate to request an investigation or to sanction misconduct”, she explains. Moreover, there is no incentive for universities to address complaints of power abuse because public cases can jeopardize their reputations — and potentially affect external funding, says Kübler.

Menzel-Riedl says that the aim of the German Rectors’ Conference is to make sure its complaint process is easily identified by Germany’s 700,000 early-career researchers. If a PhD student wants to complain, the first step is to seek advice, a process that can be anonymous, she explains. However, “if the person decides to issue a formal complaint, they will have to reveal their name, according to labour laws in Germany,” adds Menzel-Riedl.

Lasser is concerned that factors such as issues of power abuse and the precarity of PhD contracts that are shorter than three years could make Germany less attractive to top students. “I’ve seen PhD students turn down offers because they figured out the job was in a toxic environment,” says Lasser.

‘I am Hanna’

Perennial discontent about short-term contracts was exacerbated by a video released by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research in 2020. It featured a fictional character called Hanna who defends Germany’s 12-year limit on the time an early-career researcher can be employed on short-term contracts, which includes 6 years pre-PhD and 6 years post-PhD, as a way to encourage universities to offer more tenured positions. But without the addition of such positions, the system results in the subsequent loss of highly qualified academics. In response, Amrei Bahr, a junior professor in the philosophy of technology, who is on a contract at the University of Stuttgart, Germany, and her colleagues launched #IchbinHanna (#IamHanna) on Twitter, now called X, which led to thousands of scholars tweeting their stories about the precarity of short-term contracts.

“We really need to take a look at how the system enables abuse — it does so by those fixed-term contracts,” which can make researchers accept toxic working conditions, says Bahr. “If you are a funding king, you can do almost anything,” she says. Kübler agrees. The universities would suffer without the external funding brought in by these senior researchers, she says.

Amrei Bahr advocates for changes that would put junior researchers at less risk of bullying.