The main campus for the US National Institutes of Health is located in Bethesda, Maryland.Credit: Philip Scalia/Alamy

A forthcoming policy from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) will target — and at least temporarily stop — funding to laboratories and hospitals outside the United States, threatening thousands of global-health projects and international collaborations on topics such as emerging infectious diseases and cancer.

Will US science survive Trump 2.0?

The NIH, the world’s largest funder of biomedical research, plans to release the policy in the next week. Some agency staff members have already been instructed to hold funds for foreign institutions that are part of both new research grants and grants coming up for renewal, according to multiple agency employees who spoke to Nature under the condition of anonymity because they are not authorized to speak to the press.

“These decisions will have tragic consequences,” says Francis Collins, a geneticist who led the NIH, based in Bethesda, Maryland, for 12 years under three US presidents. As part of its effort to reduce federal spending, the administration of US President Donald Trump has already effectively shuttered the US Agency for International Development, which funded research, prevention and care for diseases worldwide. Combined with that action, Collins says, halting NIH foreign awards means that “more children and adults in low-income countries will now lose their lives because of research that didn’t get done about diseases like malaria and tuberculosis”.

At the time Nature published this story, it was unclear when the policy would take effect, and whether it would apply to all research funds to non-US institutions or only ‘subawards’, which are NIH funds that a US researcher can give to an international collaborator to help complete a project. It was also unclear whether the agency would try to claw back funds for existing foreign subawards.

Spokespeople for the NIH and its parent organization, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), based in Washington DC, confirmed that a policy about research abroad is coming in the next week and added that “no final decisions” on its text have been made. They disputed that the NIH had officially told agency staff members to hold foreign funds ahead of the policy release and declined to answer questions about the policy or scientists’ concerns about it until the document is released.

Broad implications

Agency employees tell Nature that they expect the policy will target funding to institutions outside the United States, regardless of whether they are located in US-designated ‘countries of concern’ such as China or North Korea, or in an ally nation such as the United Kingdom.

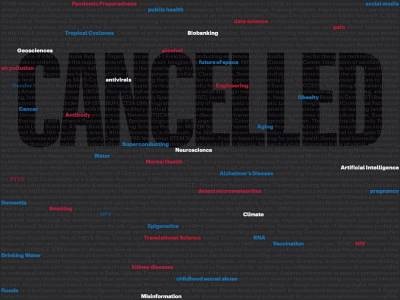

How Trump 2.0 is slashing NIH-backed research — in charts

The policy could be wide-reaching: in 2023, about 15% of the NIH’s grants included at least one ‘foreign component’, which is agency parlance for either collaboration with or financial support for researchers outside the United States, according to a former senior NIH employee, who requested anonymity out of fear of retribution. In that same year, the countries responsible for the most foreign components in agency grants were the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany and Australia, they say. It’s unclear whether the agency’s new policy will target both collaborations with and financial support for international scientists, or only grants involving funding.

Much US-backed research that is conducted abroad is on global-health topics such as cancer, maternal and child health and infectious diseases such as AIDS, Ebola and tuberculosis. “Disease outbreaks that start anywhere in the world can reach our shores in hours,” Collins says. “To just pull the plug is short-sighted and self-defeating.” If the United States pulled back all of its global health funding — which was US$12 billion in 2024 — roughly 25 million people could die in the next 15 years, according to models.

Amy Bei, a malaria specialist at the Yale School of Public Health in New Haven, Connecticut, who collaborates with researchers in Senegal, says, “we can’t do cutting-edge malaria research from the United States”, because the disease is not prevalent in the country. “If you want to move the needle on the most pressing global-health problems, this requires pulling from the best minds in the field” across the world, she says.

Cancer research could be heavily impacted too, says Yu Chen, a chronic-diseases epidemiologist at NYU Langone Health in New York City, who helps to lead a massive consortium of cancer researchers in 20 countries. For rare cancers, it’s crucial to pool data from cohorts all over the world, Chen says. “Together, we can have larger sample sizes and do meaningful research.”

Collecting clinical-trial data from other countries also helps to ensure that research findings are robust and applicable for as many people as possible, Chen adds. “We do research for the American people, but that doesn’t mean the research needs to only be done in the United States,” she says.