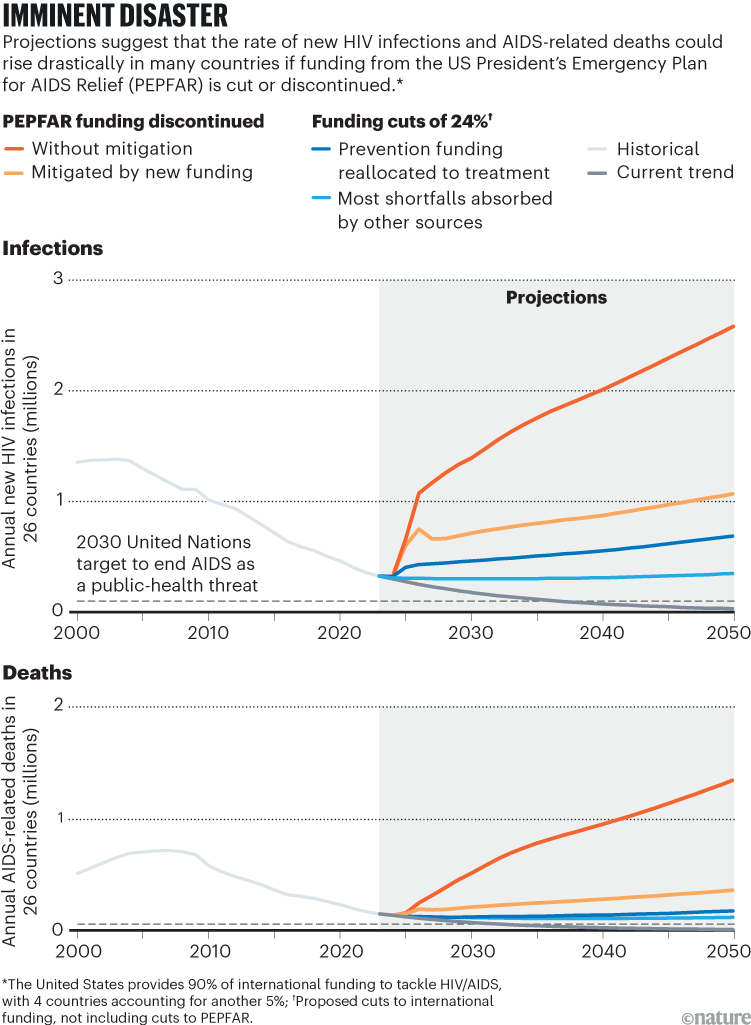

In 2024, the United States helped to provide HIV treatment to more than 20 million people around the world. It tested 84 million people for the virus and provided preventive care for several million more. All of that changed in late January, when 270,000 health-care workers, who were supported by the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), were told to stop all patient care. Although the administration had characterized it as a pause and says that it has resumed some of PEPFAR’s funding, the future of the programme is in serious doubt. If global health funding is not restored, researchers estimate that by 2030, there could be as many as 11 million extra HIV infections and 3 million extra deaths due to AIDS1 (see ‘Imminent disaster’). Some estimate as many as 15 million deaths by 2040.

PEPFAR has been one of the most successful global health projects in history, financing about 70% of the overall HIV/AIDS response and saving 26 million lives. In the first three months of his second term, US President Donald Trump has thrown the programme into chaos and dismantled the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), which ran the majority of PEPFAR’s programming. In late March, Congress failed to reauthorize PEPFAR, plunging it into purgatory.

Source: Ref. 1

“It’s an abandonment of care,” says Eric Goosby, former US global AIDS coordinator and an infectious-disease physician at the University of California, San Francisco.

Beyond reversing decades of global health progress, these actions have also upended a historic push to end the AIDS epidemic by 2030, a goal defined by the United Nations as a reduction in new infections and AIDS-related deaths to 10% of their 2010 levels.

The end of AIDS is in sight: don’t abandon PEPFAR now

Reaching the ‘AIDS endgame’ was always ambitious, but the world had amassed an arsenal of treatment, prevention and management strategies to fight the disease. And although progress faced considerable headwinds before Trump took office this year, many thought that such a goal was achievable.

Now, as the United States demolishes its foreign-aid infrastructure and global health groups attempt to salvage the pieces, some advocates are hoping that countries will take ownership of their AIDS response and create programmes that are more accountable and more innovative than before.

Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) will have their work cut out, says Pallabi Deb, senior programme manager for the HIV Vaccine Trials Network at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle, Washington. “This is a wake-up call.”

Why the endgame seemed possible

It was in Geneva, Switzerland, in 2014 that the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) raised the prospect of ending the epidemic. Deaths had fallen substantially from their peak a decade earlier (the decline even beat targets set by the UN’s Millennium Development Goals in 2000). So, to drive progress towards the finish line, UNAIDS outlined a bold plan. “This is an epidemic that no one thought we could end, but now with the progress we see, we know it can be done,” said Ghana’s President John Mahama in 2014.

Trump team guts AIDS-eradication programme and slashes HIV research grants

Beyond the strong political and financial commitment at the time, what made the endgame attainable was an unprecedented understanding of AIDS. “We understand how this virus moves through an individual, attacks their immune system, what parts are attacked more preferentially, how they decline in function,” Goosby says.

Research enabled the development of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) — medication that prevents HIV infection — and antiretroviral therapies that suppress viral replication and stop transmission. They transformed HIV from a fatal diagnosis into a manageable, preventable chronic condition, according to Deb.

As recently as the early 2000s, a positive HIV test was a death sentence in most LMICs, says Ntombi Ginindza, a former nurse in Mbabane, Eswatini, a small country sandwiched between Mozambique and South Africa. The AIDS epidemic cut nearly two decades from life expectancy there, bringing it down to just 39 years in 1998.

Today, however, Eswatini boasts one of the world’s most successful responses. With antiretrovirals freely available, mainly funded by PEPFAR, the country has reached UNAIDS’s coveted 95-95-95 target: 95% of people living with HIV know their status, 95% of those who know their status take antiretrovirals, and 95% of individuals on these drugs have undetectable levels of HIV in their blood. With the right tools and support, even the hardest-hit countries can reverse course and get within striking distance of the AIDS endgame, Ginindza says.

Advances in prevention have made the landscape even more promising. Lenacapavir, a therapy that the US Food and Drug Administration is expected to approve in June, showed remarkable results in a clinical trial in South Africa and Uganda last year. More than 2,000 girls and young women received a shot of lenacapavir every six months, and it completely prevented HIV infections — an extraordinary 100% efficacy2. These results were quickly replicated in a larger study involving six countries in Africa, Asia and the Americas3.

In 2024, PEPFAR provided services to 6.6 million orphans, children and carers.Credit: Thomas Mukoya/Reuters

Lenacapavir could revolutionize HIV prevention because it is more effective and practical than oral PrEP, and is thus a better fit for those worried about the visibility — and potential stigma — of taking a daily pill. “I love lenacapavir because it’s twice a year, very discreet,” says Doreen Moracha, an HIV activist in Nairobi, Kenya, who has been living with the virus for 32 years. The drug’s developer, Gilead Sciences, based in Foster City, California, has even started to see promising results with a once-yearly formulation4.

But because of cost concerns and regulatory delays, getting lenacapavir to where it’s needed most will be challenging, says Nittaya Phanuphak, executive director of the Institute of HIV Research and Innovation in Bangkok. Still, she is hopeful about a promised partnership between Gilead Sciences and generic manufacturers to make low-cost doses of lenacapavir for 120 LMICs.

This agreement speaks to a broader pattern, in which grass-roots activism and market interventions have put life-saving tools within reach of millions. Since 2000, pharmaceutical companies have adopted differential pricing, lowering the cost of branded antiretrovirals on the basis of a country’s income, region and HIV burden. In parallel, some governments, including Thailand’s, have invoked public-health exemptions to bypass patents and produce affordable generic drugs domestically.

As of 2023, HIV infections globally were down by 39% from 2010 levels, and AIDS-related deaths dropped by 51% to 630,000. For many working in this field, decades of scientific advances and public-health progress had put the AIDS endgame within reach.

Complacency and chaos

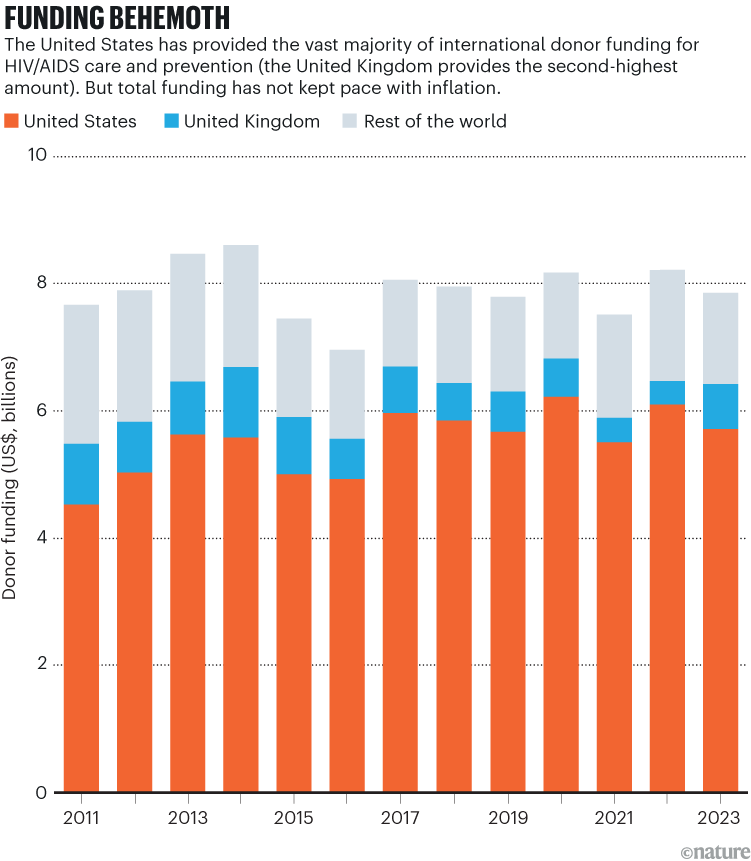

There were concerns, however, that pre-dated the Trump administration’s withdrawal of funding. As AIDS deaths declined and living with an HIV infection became more manageable, it was increasingly difficult to evoke the same urgency and political will, says Brendan Bell, a microbiologist at the University of Sherbrooke in Canada. In 2023, countries’ domestic funding to tackle HIV declined for the fourth year in a row, whereas international financing has been falling from its peaks in the early 2010s (see ‘Funding behemoth’). “We’ve become victims of our own success,” Bell says. “With the success of antiretrovirals, why go further?”

Source: A. Wexler et al. KFF/UNAIDS (2024); https://go.nature.com/3GSBELW

Fading memories have also stalled social-policy reforms, such as the decriminalization of sex work, drug use and same-sex relationships. Much research shows that fear of discrimination and criminal penalties discourages high-risk populations from accessing PrEP and testing, increasing people’s likelihood of getting HIV and being diagnosed late5. As a result, sex workers, people who use drugs and people from sexual and gender minorities (LGBT+) have sometimes been left out of global progress against AIDS. “You can’t have an impact on these populations without working openly with them,” says infectious-disease physician Sharon Lewin, who heads the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity in Melbourne, Australia.

Complacency is especially common among younger generations, who never witnessed the full horror of the AIDS epidemic, Moracha says. More than one-quarter of new HIV infections are in people aged 15–24 years old, in part because of declining condom use and low testing rates. “There is now a whole new generation that doesn’t see HIV as a big deal,” she says.

HIV: how close are we to a vaccine — or a cure?

The world will soon get a reminder. The virus starts replicating 6–8 hours after a person with HIV stops taking antiretrovirals. Within a week, their viral load becomes measurable. With waves of HIV leaking into the bloodstream, after four to six weeks, white blood cells start to get chewed up, leaving the body vulnerable to opportunistic infections. “The average number of infections you’d get through is three or four, before it kills you,” Goosby says. Give it three to six months, and hospitals will be overrun with HIV patients who will die in hallways, car parks and overflow tents, he predicts.

Deaths can also happen much sooner than that, for example in infants who have underdeveloped immune systems, or in people with advanced disease succumbing to malaria and other infections. Since Trump’s foreign-aid freeze in late January, an estimated 41,000 adults and 4,500 children living with HIV have died. That is one person roughly every three minutes, according to the PEPFAR Impact Counter, a data dashboard funded by the Center on Emerging Infectious Diseases at Boston University in Massachusetts. “The extraordinary infrastructure that’s delivered antivirals to 70% of people living with HIV can be unravelled in days,” Lewin says.

A statement from a White House official says that mechanisms to serve 85% of PEPFAR beneficiaries are “up and running”, and that it is working with USAID to “rebalance” awards that don’t fit with the administration’s priorities. The statement said that the administration has a “glide path to self-reliance for PEPFAR countries” and that it has seen positive movement to that end over the past two months. The 85% figure seems to apply to treatment efforts and not to prevention programmes. And even supposedly resumed programming has hit roadblocks thanks to the hollowing out of USAID. Requests from Nature for further clarification from White House officials were not answered.

Condoms being distributed in Bangkok.Credit: Peerapon Boonyakiat/SOPA Images/LightRocket/Getty

Terminated research grants from USAID and the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) have also derailed promising advancements and innovations, says Glenda Gray, chief scientific officer at the South African Medical Research Council in Cape Town. For example, Gray’s experimental HIV vaccine trial was shut down, and Phanuphak recently had to close about half of the Institute of HIV Research and Innovation, despite its strong history of testing life-saving interventions. As of early April, nearly 30% of terminated NIH grants were related to HIV/AIDS.

Phanuphak also worries that Trump’s executive orders, such as ones declaring that there are only two genders and placing restrictions on funding for organizations that “promote gender ideology”, will further undermine HIV policy reforms. Thailand, for example, continues to criminalize sex work, ban the distribution of clean needles and syringes and disallow legal gender recognition for transgender individuals. She thinks that, because of US actions, Thai policymakers could be more emboldened to block ongoing reform efforts. “It’s not an enabling environment to tackle HIV,” Phanuphak says.