Researchers in the United States are seeking career opportunities abroad as President Donald Trump’s administration slashes science funding and workforce numbers, finds an analysis of Nature’s jobs-board data.

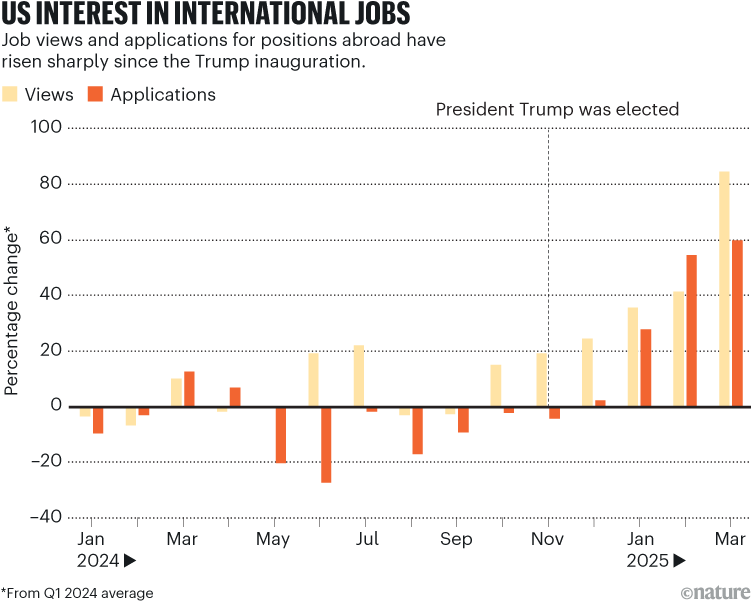

Data from the Nature Careers global science jobs platform show that US scientists submitted 32% more applications for jobs abroad between January and March 2025 than during the same period in 2024. At the same time, the number of US-based users browsing jobs abroad increased by 35%.

In March alone, as the administration intensified its cuts to science, views rose by 68% compared with the same month last year.

More than 200 federal grants for research related to HIV and AIDS were abruptly terminated last month. Cuts to grants from the US National Institutes of Health for COVID-19 research were revealed, and the government began a US$400-million reduction in research grants at Columbia University in New York City, because of campus protests supporting Palestinians in the conflict with Israel.

“To see this big drop in views and applications to the US — and the similar rise in those looking to leave — is unprecedented,” says James Richards, who leads the Global Talent Solutions team at Springer Nature, which includes the Nature Careers multidisciplinary science jobs board. As this article went to press, the board hosted 983 live vacancies.

The team shared the data with Nature journalists on condition that its analysis was confined to percentage changes rather than raw numbers, on the grounds that the information is considered commercially privileged. Nature’s journalists are editorially independent of Springer Nature, its publisher.

The release of the Nature Careers jobs-board data follows a separate poll of researchers by Nature’s news team, which found that 75% of researchers in the United States who responded were keen to leave.

US President Donald Trump has planned sweeping cuts to research instiutions during his time in office.Credit: Ben Curtis/AP/Alamy

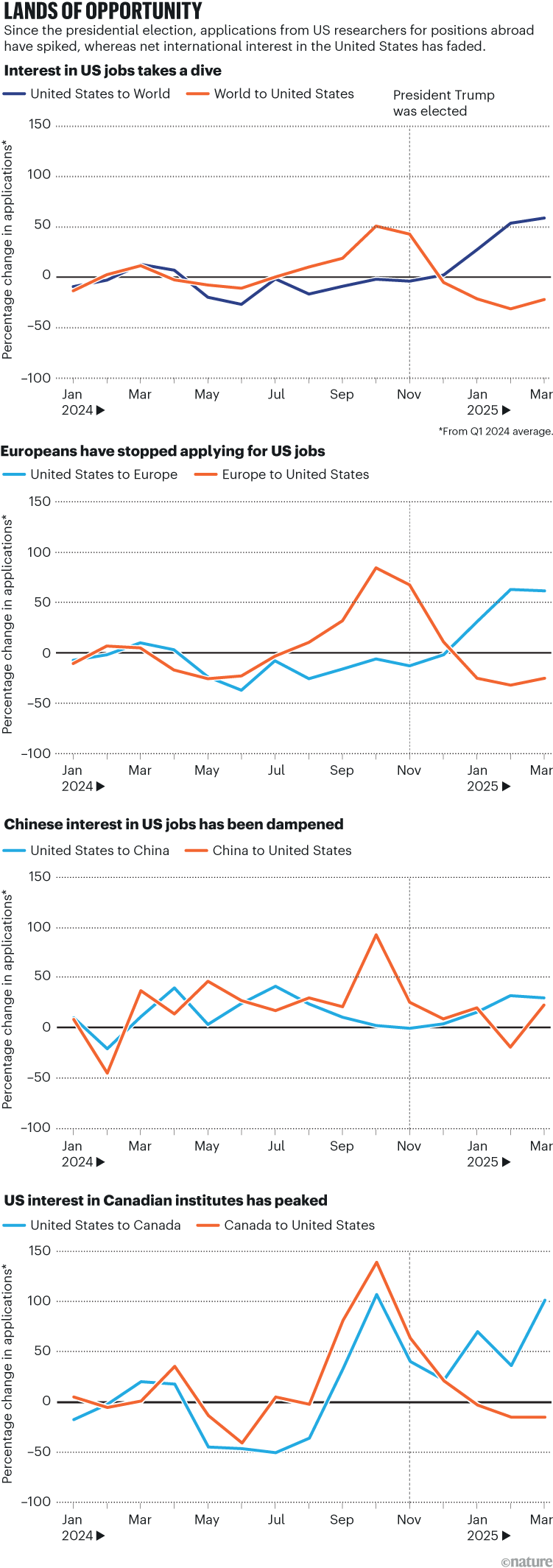

Applications from US scientists seeking career opportunities in neighbouring Canada increased by 41% between January and March 2025 compared with the same period in 2024. By contrast, applications from Canadian researchers for jobs in the United States dropped by 13%.

Chemical engineer Valerie Niemann is one of many looking beyond the United States to develop her career. This month, she moved from Stanford University in California to take up a postdoctoral position at the University of Bern.

In the United States, she says, “people don’t know how long their postdocs will be. We can’t apply for fellowships because we don’t know how long they’re going to exist.”

In a 25 March post on the social media platform X, Xiao Wu, a biostatistician at Columbia University, lamented: “My very first NIH grant was abruptly cancelled just three months after receiving funding.” His work focuses on using evidence-based data to mitigate the harms of climate change on health.

Wu is not currently looking for work elsewhere, but fears he might eventually have no choice. “Without these grants, my career stability and professional future are directly jeopardized,” he says. “Therefore, this situation is not simply one of ‘seeking other opportunities’, but rather one where we are effectively being forced out of US academic institutions.” (See ‘US interest in international jobs’.)

Bring me your huddled masses

Some European institutions are scrambling to attract what might be an exodus of scientific talent from the United States.

In early March, for example, Aix-Marseille University in France, launched the Safe Place for Science initiative. It has allocated €15 million (about US$17 million) from the university’s budget to sponsor 15 researchers working on climate, health, the environment and social sciences.

Aix-Marseille spokesperson Clara Bufi says that the university closed the application window after receiving an overwhelming 298 applications and nearly 400 requests for information, but adds that it might reopen it after processing the current applications. The programme is aimed at US researchers who have been dismissed, censored or prevented from working by the Trump administration’s actions. Seventy per cent of applicants are researchers from the United States and are specialists in their fields, she says, and 20 people will now be selected this year.

“What’s happening is terrible for American research,” says Aix-Marseille’s president, Éric Berton, adding: “We felt it was our duty to do what we could to show scientists there was a little light in the south of France where they could do their research, be a lot freer and where they were wanted.”

Berton’s message seems to be a compelling one. Applications from the United States to fill European vacancies on the Nature Careers jobs board increased by 32% in March compared with the same month a year earlier, and views increased by 41%.

At the same time, applications to US institutions from researchers in Europe dropped by 41%.

The Max Planck institutes in Germany have been fielding requests from some of their researchers who are from the United States but who would like to stay in Germany longer than they’d planned.

Does US science have a future in Antarctica? Trump cuts threaten to cancel fieldwork and more

Christina Beck, a spokesperson for the institutes, says that more applications are arriving from Asian countries, too, attributing the rise to “scientists possibly reorienting themselves, and preferring Europe to the US”. She adds: “We are following the situation in the US closely and are very concerned about the encroachments on academic freedom and institutional autonomy there.”

On 7 April, Patrick Cramer, president of the Max Planck Society in Munich, Germany, announced the formation of the Max Planck Transatlantic Program. The initiative sets out plans to create collaborative research centres with US-based institutions, as well as providing further postdoctoral training posts, and extra places for junior investigators at the society’s 84 institutes. It will also offer director positions to some “outstanding investigators” who are no longer able to work in the United States.

The entire international jobs market has seen a spike in activity (see ’Lands of opportunity’). Views and applications for non-US jobs posted on the Nature Careers website by researchers outside the country were 13% higher in January to March 2025 than they were in the same period last year.

But researchers planning to flee to Europe from the United States shouldn’t expect an open position to be waiting for them.