The dismantling of the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and reductions in aid budgets over the next 3–5 years announced by other Western donor countries, including the United Kingdom (40%), France (37%), the Netherlands (30%) and Belgium (25%), threaten to reverse decades of progress in reducing malnutrition1.

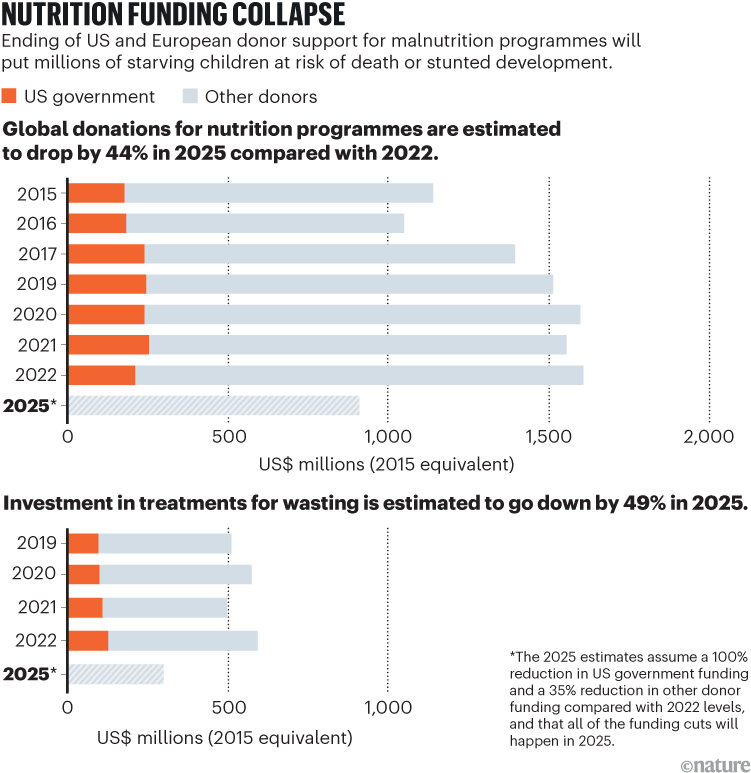

These cuts — equivalent to 44% of the US$1.6 billion in donor aid provided in 2022 to support the World Health Assembly nutrition targets — will lead to hardship and death among the most vulnerable people in the world2. The implications for public health, economic growth and societal stability are profound.

Severe acute malnutrition, or severe wasting, is the most lethal form of undernutrition and is responsible for up to 20% of deaths of children under the age of five years, and affects 13.7 million children a year worldwide. Left untreated, up to 60% of affected children might die3.

How Trump 2.0 is reshaping science

Proven programmes, such as community-based management of severe acute malnutrition, which combine screening, treatment and counselling, can reduce mortality to below 5%3 and have been used in more than 70 countries. In 2022, the United States and other donors reporting to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development spent $591 million on severe-wasting treatment2, which was matched by receiving countries.

The abrupt withdrawal of donor support leaves millions of critically ill children without access to these life-saving programmes. It is already undermining the institutional capacity, expertise and data infrastructures required to deliver essential nutrition services.

For example, in Nigeria, withdrawal of USAID Advancing Nutrition funding has meant that the charity Helen Keller International has had to stop a programme that provides nutrition services for 5.6 million children. In Sudan, almost 80% of emergency food kitchens are closed. In Ethiopia, supplies of nutrient-rich foods used to treat around one million severely malnourished children annually will run out by May. And the global FEWS-NET network — a leading source of data on famine risks — sits idle, disrupting early-warning systems for humanitarian planning and emergency resource allocation.

Loss of donor funding is also jeopardizing the procurement and distribution of ready-to-use therapeutic food, a life-saving treatment for severe acute malnutrition. The product comes as a dense micronutrient paste that contains peanuts, milk powder, sugar, oils, vitamins and minerals. USAID supported half of the world’s supply4.

The impacts of these cuts will be dire. To illustrate, here we assess their scale.

Millions of lives in peril

Altogether, we estimate that reductions of $290 million in donor funding for severe acute malnutrition (see ‘Nutrition funding collapse’) will cut off treatment for 2.3 million children in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). This would lead to 369,000 extra child deaths a year that would otherwise have been prevented.

Source: Ref. 2

Of those, the termination of US-funded programmes (worth $128 million in 2022) alone will keep one million children from accessing such treatments, causing an extra 163,500 child deaths yearly.

These worst-case scenarios are based on 2022 donor disbursement data for severe wasting treatment, drawn from the Creditor Reporting System of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and analysed by Results for Development, a global non-profit organization2 (see Supplementary information). These treatments are included in community-based management of severe acute malnutrition programmes, which screen and treat children with severe acute malnutrition and follow them to prevent relapse after recovery.

Will RFK Jr’s vaccine agenda make America contagious again?

Cutting all US financing and on average 35% of aid from other donors results in $704 million less funding for nutrition programmes overall, and $290 million less for severe acute malnutrition treatment. These numbers assume that disbursements would have otherwise been similar to those in 2022, that the 35% average cuts to aid that were announced by European donor countries will reduce funding for nutrition by 35%, and that donor funding is matched by contributions from LMIC governments, as is often the case.

The No Time to Waste report4 by the United Nations children’s fund UNICEF estimated that 1.2 million deaths were averted in 2023 by treating 7.4 million children with severe acute malnutrition in 47 high-risk countries. Because 80% of cases worldwide were in these countries, we increased these numbers to cover 100% of cases globally, to 9.3 million children treated and 1.5 million deaths averted.

We calculated the percentage of reduction in donor funding compared with the 2022 disbursements and assessed how many of the children treated in 2022 would now not receive aid. Similarly, we analysed how many of the prevented deaths because of treatment in 2022 would now not be averted.

Global consequences

Although shocking, the number of deaths might be an underestimate, because the aid cuts threaten a huge array of nutrition-supporting programmes, including health, agriculture, school feeding and water and sanitation. Soon we might see many more millions of children around the world developing wasting, stunted growth and micronutrient malnutrition.

Severe wasting is responsible for up to 20% of deaths of children under the age of five.Credit: Tiksa Negeri/Reuters