Health-care staff in Texas are racing to vaccinate infants against measles as an outbreak in the state spreads.Credit: Jan Sonnenmair/Getty

A measles outbreak in the United States is growing , with no end in sight. As of 18 March, 279 cases had been reported in Texas, 38 in neighbouring New Mexico and as many as 4 in Oklahoma, which also borders Texas. Measles has killed an unvaccinated six-year-old child in Gaines County, Texas, the centre of the outbreak, and is the suspected cause of death of an unvaccinated adult in New Mexico.

“We haven’t yet seen signs of the outbreak slowing down,” says William Moss, an infectious-disease epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland.

Even as health officials try to stop the outbreak, the US Secretary of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr, who has a long history of anti-vaccination activism, has offered only tepid support for the measles vaccine, a safe and potent way to prevent infection. Kennedy has also promoted treatments including cod liver oil, steroids and antibiotics, none of which are known to be effective against measles. (Kennedy has said that he does not oppose vaccination, but that it should be a “personal” choice.)

Nature asked specialists how bad things could get.

How big could the outbreak become?

That’s hard to predict. A measles outbreak is like a forest fire throwing out sparks, Moss says. If a spark lands in a state such as Maryland, which has a 97% measles vaccination rate, it will just fizzle out. But “if the sparks from this initial fire land in communities where vaccination rates are low, then we’re going to have multiple large outbreaks”, Moss says.

“I think it could get to thousands and thousands of cases,” says virologist Paul Offit at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania.

Why is measles so incredibly infectious?

Measles is the most contagious disease that is transmitted directly between people. Epidemiologists use a metric called R0 to indicate how many people, on average, one person with a given illness is expected to infect. The R0 for measles is a whopping 12–18. By comparison, the R0 for COVID-19 at the start of the pandemic was estimated to be about 1.4–2.5, and the R0 for influenza is about 1–2.

Measles is so contagious that in 1991, a single athlete with measles in a sports stadium infected 16 other people, including 2 sitting at least 30 metres away (about the length of a gymnasium).

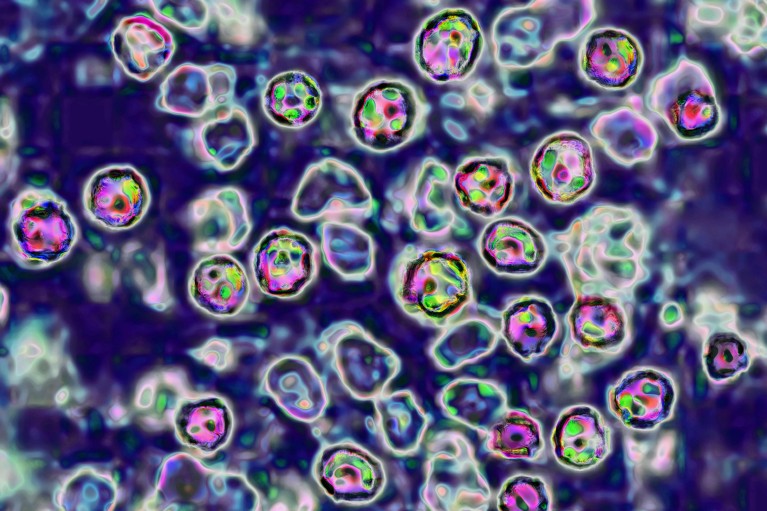

Particles of measles virus (artificially coloured), one of the most infectious pathogens known.Credit: Cavallini James/BSIP/SPL

Measles is virulently contagious partly because the dose needed to infect someone is very small. Moreover, the measles virus spreads through airborne droplets when an infected person so much as breathes. If someone with measles passes through a room, infectious droplets can hang in the air or rest invisibly on surfaces for two hours afterwards.

What’s more, in the first 2–4 days, the illness often features symptoms — such as a fever, cough and runny nose — that can fool people into thinking they have a cold. As a result, people with measles might not isolate when they are highly contagious. The disease’s telltale red spots don’t usually appear until several days into the illness.

What are the long-term effects of measles?

Measles can kill: between about one and three cases in every 1,000 unvaccinated children is fatal. Roughly 5–6% of infected people develop pneumonia, which is the most common cause of death in young children with measles. Measles can also cause blindness or hearing loss.

One of the most eerie long-term effects is a rare, almost always fatal complication called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. It develops years after a measles infection and is characterized by cognitive decline, personality changes and dementia.

Another long-term effect is ‘immune amnesia’. Measles can wipe out large numbers of antibodies that store the body’s memory of how to fight other diseases. There’s evidence that measles could leave the immune system more susceptible to other diseases for some 2–3 years after infection1.

Even acute symptoms of measles can be very unpleasant. They include mouth ulcers, ear infections, croup, laryngitis and diarrhoea.

“The way we stop this is to vaccinate,” Moss says.