Chetan Nayak leads Microsoft’s quantum computing effort.Credit: John Brecher for Microsoft

Anaheim, California

A Microsoft researcher today presented results behind the company’s controversial claim last month to have created the first ‘topological’ qubits — a long-sought goal of quantum computing.

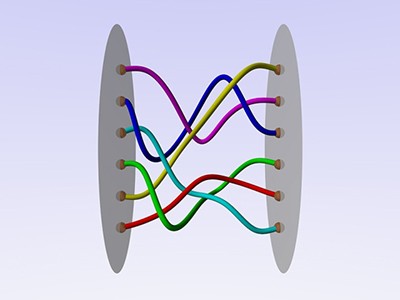

Inside Microsoft’s quest for a topological quantum computer

In front of a packed room at a meeting of the American Physical Society (APS), Chetan Nayak, a theoretical physicist leading Microsoft’s quantum computing effort in Redmond, Washington, explained how the company is developing topological qubits, which would be the building blocks for a noise-resistant quantum computer.

Physicists in the audience told Nature’s news team they are still unsure whether Microsoft really has made the first topological qubits, however. “It’s a hard problem,” says Ali Yazdani, an experimental physicist at Princeton University in New Jersey. To anyone trying to make topological qubits, he says, “good luck”.

“It was a beautiful talk,” says Daniel Loss, a theorist at the University of Basel in Switzerland. But he took issue with the strong claims and relative lack of evidence. “People have gone overboard, and the community is not happy. They overdid it,” he says.

Nayak acknowledges the criticism: “I never felt like there would be one moment when everyone is fully convinced,” he says, adding that Microsoft is confident in its understanding of the devices, and that other researchers are excited by the work.

Qubit cliffhanger

The standing-room-only APS talk was hotly anticipated in physics circles. Microsoft announced that it had created the first topological qubits on 19 February in a press release. But some physicists were unsure whether the claim would hold because there was no peer-reviewed scientific paper to back it up. (Microsoft published a paper in Nature at the same time as its initial announcement, but the paper described a way to take a read-out from future topological qubits rather than proving their existence1).

Evidence of elusive Majorana particle dies — but computing hope lives on

Two weeks later, physicist Henry Legg of the University of St Andrews, UK, cast further doubt on Microsoft’s claim when he posted a report on the preprint server arXiv, ahead of peer review, that pokes holes in a test that the company uses to verify its quantum-computing devices2. Legg presented these findings at the APS conference on Monday.

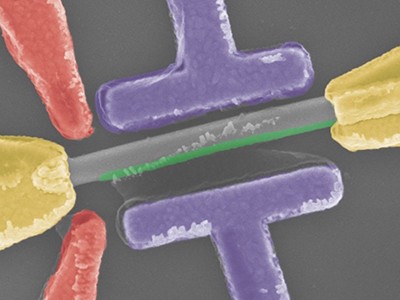

Meanwhile, in today’s talk, Nayak displayed a schematic for Microsoft’s qubits: they are microscopic, H-shaped aluminium wires on top of indium arsenide, which is a superconductor at ultracold temperatures. The devices are designed to harness Majoranas, previously undiscovered ‘quasiparticles’ that are essential for topological qubits to work. The goal is for the Majoranas to appear at the four tips of the H-shaped wire, emerging from the collective behavior of electrons. These Majoranas, in theory, could be used to perform quantum computations that are resistant to information loss.

The new data that Nayak presented were primarily of ‘X’ and ‘Z’ measurements of the qubits, which are vertical and horizontal probes along the H-shaped wire. When Nayak showed data for the X measurement, he acknowledged that the characteristic bimodal signal was hard to see by eye because of electrical noise.

Eun-Ah Kim, a theorist at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, therefore questioned the robustness of the X measurement. “I’d like to see the bimodality be easily visible in future experiments,” she told Nature’s news team.