Device fabrication

We fabricate the GaP photonic chip using a process similar to that outlined in the Supplementary Information of ref. 14. We epitaxially grow thin films by metal–organic chemical vapour deposition on a sacrificial [100]-oriented GaP wafer that is repolished before growth to mitigate the formation of hillocks. Hillocks form as a result of surface contamination of the as-received commercial GaP wafers and lead to bonding defects. The grown layers consist of a 100-nm-thick GaP buffer layer, a 200-nm-thick Al0.2Ga0.8P layer (later used as an etch-stop layer to selectively remove the sacrificial wafer) and a 299-nm-thick GaP device layer. The surfaces of both the GaP wafer following growth and of a silicon wafer capped with 2 μm of SiO2 are prepared for wafer bonding by depositing 5 nm of Al2O3 by thermal atomic layer deposition. After bonding, the wafer is annealed to improve the strength and stability of the bond. The sacrificial GaP wafer is then removed by mechanical grinding, down to a thickness of about 50 μm. The remaining portion of the sacrificial GaP wafer is dry-etched on the chip level in a mixture of SF6 and SiCl4 in an inductively coupled plasma reactive-ion etching process49. The etch rate slows substantially once the Al0.2Ga0.8P layer is exposed to the plasma. Subsequently, the Al0.2Ga0.8P stop layer is selectively removed by wet-etching in concentrated HCl for 4 mins. The surface of the chip is promptly covered with 3 nm of SiO2 deposited by plasma atomic layer deposition at a temperature of 300 °C. This thin layer of SiO2 also acts as an adhesion promoter for the negative resist hydrogen silsesquioxane that is used to pattern the devices by means of electron-beam lithography. The spirals are designed to fit in a single 525 × 525-μm electron-beam write field to mitigate possible scattering losses that may originate from the imperfect stitching of neighbouring write fields. The resist pattern is transferred into the GaP by inductively coupled plasma reactive-ion etching using a mixture of BCl3, Cl2, CH4 and H2 (ref. 13), after which the hydrogen silsesquioxane is removed by dipping the chip in buffered hydrogen fluoride for 10 s. A 2-μm-thick SiO2 top cladding is applied by means of plasma-enhanced chemical vapour deposition using tetraethyl orthosilicate as precursor at 400 °C. Efficient input and output coupling of the light is enabled by 250-μm-long inverse tapers with a design tip width of 180 nm. The edges of the chip are removed by subsurface-absorption laser dicing to expose the inverse tapers, providing clean vertical chip facets and efficient fibre-to-chip coupling to reduce the overall optical insertion loss.

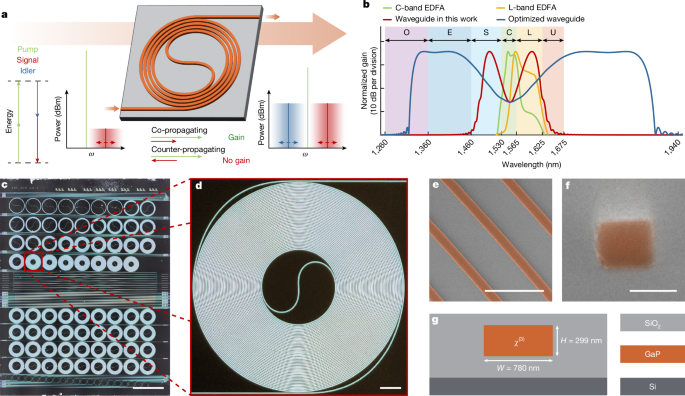

Dispersion engineering of GaP waveguides for optical parametric amplification

In strongly confining integrated waveguides, such as those made of GaP, it is possible to tune the group velocity dispersion β2 and the zero-dispersion wavelengths over a wide range by varying the cross-sectional geometry50,51. We therefore perform dispersion simulations of straight rectangular GaP waveguides fully cladded with SiO2 for a range of film thicknesses and waveguide heights and widths using a commercially available finite-element-method solver, COMSOL Multiphysics, as depicted in Extended Data Fig. 1. We find that the thickness of the GaP cannot be less than about 270 nm, otherwise dispersion is normal and only a relatively weak parametric gain is possible in a narrow window near the pump wavelength.

For the prepared GaP layer thickness of 299 nm, we design a waveguide with a width of 790 nm to operate in the anomalous dispersion regime. We also fabricate waveguides with smaller widths, varied in steps of 5 nm. Note that, because of the strong mode confinement, the difference between the dispersion of a straight waveguide and that of a bent waveguide is negligible for bending radii ≳50 μm. In our Archimedean spiral waveguides, the bending radius changes from 250 μm to approximately 80 μm. It may be possible to increase the amplification bandwidth further by increasing the GaP waveguide height to about 330 nm because the contribution of the fourth-order dispersion parameter is near zero and varies less with the waveguide width at this thickness, thus leading to more broadband amplification and a more robust waveguide design.

In our main experiments, we use waveguides that are 5.55 cm long, including the straight waveguide sections and the input and output inverse coupling tapers, as well as the spiral itself. The parametric amplification bandwidth depends on the accumulated phase mismatch between pump, signal and idler and, therefore, on the propagation constant mismatch and the device length46. Hence it is generally beneficial to use shorter devices to prevent bandwidth narrowing. Moreover, short devices are less sensitive to cross-section variations that could potentially lead to further bandwidth degradation.

Numerical calculations of optical parametric gain

Numerical calculations of the signal gain GS and idler conversion efficiency GI are performed using frequency-domain nonlinear coupled-mode equations of the complex normalized amplitudes \(A_\rmP,\rmS,\rmI=\sqrtP_\rmP,\rmS,\rmI\) of pump, signal and idler waves3

$$\beginarrayl\frac\rmdA_\rmP\rmdz\,=\,(\rmi\gamma (| A_\rmP ^2+2| A_\rmS ^2+2| A_\rmI ^2)-\alpha /2)\times A_\rmP+\rmi\gamma A_\rmP^\star A_\rmSA_\rmI\times \rme^\rmi\Delta \beta z,\\ \frac\rmdA_\rmS\rmdz\,=\,(\rmi\gamma (2| A_\rmP ^2+| A_\rmS ^2+2| A_\rmI ^2)-\alpha /2)\times A_\rmS+\rmi\gamma A_\rmP^2A_\rmI^\star \times \rme^-\rmi\Delta \beta z,\\ \frac\rmdA_\rmI\rmdz\,=\,(\rmi\gamma (2| A_\rmP ^2+2| A_\rmS ^2+| A_\rmI ^2)-\alpha /2)\times A_\rmI+\rmi\gamma A_\rmP^2A_\rmS^\star \times \rme^-\rmi\Delta \beta z,\endarray$$

(1)

in which α denotes the linear propagation loss and γ denotes the effective nonlinearity of the GaP strip waveguide. Here n2 is the nonlinear refractive index of the waveguide core and Aeff is the effective nonlinear mode area:

$$\gamma =\frac\omega _\rmPn_2cA_\rmeff,\,A_\rmeff=\frac\left(\int ^2\int .$$

(2)

All simulations are implemented in MATLAB (version 9.13.0 (R2022b)), whereas dispersion, effective nonlinearity and the effective nonlinear mode area are calculated using COMSOL Multiphysics. For more precise simulations of broadband gain, the variation of mode profile with frequency should be taken into account; the effective nonlinear mode area should be replaced with signal-frequency-dependent overlap integrals of the nonlinear interaction52. For waveguides with a width of 790 nm and height of 299 nm, we find an effective nonlinear mode area of 0.26 μm2 and an effective nonlinearity γ of 165 W−1 m−1 at a pump wavelength of 1,550 nm, with the nonlinear refractive index n2 = 1.1 × 10−17 m2 W−1. This value of γ is more than 300 times larger than that of dispersion-engineered Si3N4 waveguides11 and more than 104 times larger than typical highly nonlinear fibres8. The nonlinear coupled-mode equations are integrated using a forward Euler scheme along the waveguide spiral of length L and signal gain and idler conversion efficiency are calculated relative to the input signal power PS(0):

$$G_\rmS(L)=\fracP_\rmS(L)P_\rmS(0),\,G_\rmI(L)=\fracP_\rmI(L)P_\rmS(0)$$

(3)

In the small-signal regime, the maximum gain in a waveguide of length L is given by GS = 1 + (γPPg−1sinh(gL))2 and achieved when the linear propagation mismatch Δβ = β(ωS) + β(ωI) − 2β(ωP) ≈ β2(ωS − ωP)2 + β4/12(ωS − ωP)4 +… is compensated by the nonlinear phase-mismatch 2γPP and, therefore, is defined by Δβ + 2γPP = 0 and g = γPP, yielding GS = 1 + (sinh(−ΔβL/2))2. Extended Data Fig. 2a shows simulated amplification spectra for the optimized waveguide cross-section.

Our devices turned out to feature a more strongly anomalous dispersion than simulated, resulting in the gain profile depicted in Extended Data Fig. 2b. This discrepancy may originate from imperfections and variations in the waveguide geometry and material stack that are not considered in the simulations. The waveguide cross-section for the simulations in Extended Data Fig. 2b has been adjusted to match experimental results, giving a β2 parameter of −120 fs2 mm−1, whereas β4 has a negligible contribution. For the nominal cross-section of 789 × 299 nm2, the theoretical value would be β2 = −16 fs2 mm−1 (and β4 = 3,547 fs4 mm−1). The experimentally measured value is −124 fs2 mm−1 (Extended Data Fig. 3), which is in a good agreement with numerical simulations for the adjusted amplification spectra, given that the spiral waveguide is short and precise measurements are challenging. The value of β4 cannot be reliably determined experimentally.

We are at present performing more measurements to determine the reason for the discrepancy between the experiment and simulations and to improve the material model of GaP, which is pivotal to achieve the full potential amplification bandwidth of 500 nm. However, we are ultimately limited by fabrication tolerances. Extended Data Fig. 4 shows that the parametric gain spectra can vary substantially if the cross-section of the fabricated waveguide deviates only slightly from the design. Although variations of several nanometres in waveguide width may be acceptable, a deviation in height of only 3 nm changes the gain profile substantially.

In the literature, there is great uncertainty in the value of the nonlinear refractive index of GaP, ranging from n2 = 2.5 × 10−18 W−1 m2 (ref. 53) measured by FWM to n2 = 1.1 × 10−17 W−1 m2 (ref. 14) measured by means of the optical parametric oscillation threshold in GaP ring resonators, as well as by modulation transfer experiments. We find that, by using the smaller value, we underestimate the observed gain substantially. Using the larger value, we need to reduce the input power in the simulation by 3 dB. A similarly reduced Kerr parametric gain was recently observed in Si3N4-based waveguide spirals11,12. The first reason for this observation may be residual higher-order nonlinear absorption in the GaP waveguide, as we operate the amplifier at high input power and close to the three-photon absorption threshold. Moreover, Ye et al. have proposed that the reduced effective pump power arises owing to parasitic power transfer between different waveguide modes12. This is corroborated by the observation of substantial modulation of the transmission spectrum owing to chaotic interference of the fundamental and higher-order modes (see Extended Data Fig. 5a and the discussion below), proving that at least some of the optical power is propagating in the higher-order mode. Overall, we find that our observations support a value for the nonlinear refractive index towards the upper limit of the literature range.

Transmission characterization and loss measurements

The dispersion profile and propagation loss of the spiral are measured with a custom, all-band frequency-comb-calibrated scanning diode laser spectrometer and optical frequency-domain reflectometer (OFDR)54 over the wavelength range from 1,260 nm to 1,630 nm (refs. 11,55). We characterize the transmission of our samples at low power, as described in ref. 11. A fully calibrated transmission trace of a 5.55-cm-long spiral waveguide is shown in Extended Data Fig. 5a.

The transmission exhibits a strongly oscillating behaviour, which we attribute to the interference of the facet reflections and multimode interactions in the waveguide. At wavelengths around 1,550 nm, the overall transmission is 12%. However, during OPA gain measurements, the photonic chip is exposed to optical powers as high as 4.4 W and the transmission trace is thermally redshifted. To maintain a good coupling of the pump laser when increasing the power, we adjust the pump wavelength, increasing it typically by not more than 1.6 nm at the highest available level of pump power. In the S-band, C-band and L-band, the average loss rate is 0.8 dB cm−1 (Extended Data Fig. 5b). At shorter wavelengths, we observe increased losses that we attribute to absorption by the first overtone of the O–H stretch vibration in the low-temperature oxide cladding, which can be mitigated by using different fabrication techniques56. From these measurements, we estimate an average coupling loss rate as high as 2.5 dB per facet, assuming that the input and output facets are the same.

Optical-gain measurements

We use two widely tunable external-cavity diode lasers (TOPTICA CTL) as pump and signal sources. The pump laser is amplified using an EDFA (Keopsys CEFA-C) up to 4 W. The ASE from the EDFA is filtered out with a tunable band-pass filter (Agiltron FOTF) and the input power is controlled with a variable optical attenuator (Schäfter + Kirchhoff 48AT-0). One percent of each of the input waves is guided to power meters (Thorlabs S144C) and the rest is combined on a 10/90 fibre splitter, with the pump being injected in the 90% input. We use lensed fibres to couple light into and out of the waveguide. Of the collected light, 90% is guided to the power meter and 10% is analysed using the OSA (Yokogawa AQ6370D). All input (output) powers quoted in the figures and the text are calibrated and indicate the values at the input (output) lensed fibre tips, unless specified separately. The pump wavelength is set to 1,550 nm. For each pump-power level, we continuously scan the signal laser wavelength from 1,550 nm to 1,630 nm (which is the maximum available wavelength for the laser that we use) while simultaneously scanning the OSA using the ‘Max Hold’ function; at every new scan, the OSA records and updates only the highest values across the measurement span, while the signal laser wavelength is slowly swept to cover the entire amplification bandwidth. To ensure that measurements at different wavelengths are performed under the same conditions without marked coupling degradation during the experiment, we slow down the laser scan speed and set the OSA resolution bandwidth to 2 nm. We find that, in the optical-amplification experiments, it is paramount to ensure good thermal coupling between the photonic chip and the chip holder to avoid excessive heating of the waveguide that leads to device failure and burning of the waveguide in the inverse taper section, even at input powers as low as 1 W. We attribute this behaviour to the fact that the pump wavelength is very close to the three-photon absorption threshold (≈1,660 nm for Eg = 2.24 eV (ref. 39)) and that, therefore, the nonlinear absorption of GaP increases strongly with temperature in the telecommunication wavelength region. Similar behaviour was observed in silicon57 at telecommunication wavelengths and for GaP close to the two-photon absorption threshold58. However, by ensuring good thermal contact between the chip and metallic chip holder, we can operate the OPA at room temperature and at 4.1-W input power for hours in air without active cooling.

Parametric gain in waveguides with varying lengths

As well as the continuous-wave amplification experiments presented in the main text, we explored the behaviour of the parametric gain and the conversion efficiency in spiral waveguides with the same design cross-section (waveguide width 780 nm) but different waveguide lengths, varying the length in steps of 1 cm from 2.55 cm to 5.55 cm. The conversion efficiency and parametric gain data are depicted in Extended Data Fig. 6a,b, respectively.

Here the pump power is set to 3 W. As expected, the amplification bandwidth decreases with increasing waveguide length owing to the accumulated linear phase mismatch, in good agreement with established theory3 and previous observations46. For the shortest length, 2.55 cm, we find that the net amplification bandwidth extends substantially beyond the tuning range of our laser.

Spontaneous parametric comb formation

In doped waveguide and fibre lasers, the achievable amplification gain is limited by spontaneous lasing through parasitic reflections from chip facets and other components. For example, in recent work on erbium-doped waveguide amplifiers18, an off-chip net gain of 26 dB was achieved but required the use of index-matching gel at the fibre facet to suppress parasitic lasing. By contrast, the strong yet unidirectional gain of the GaP OPA allows us to achieve the same net gain with simple cleaved chip facets and lensed fibres without parametric lasing because the threshold for the spontaneous sideband formation is intrinsically large compared with doped amplifiers with bidirectional gain. However, operating the amplifier at 4.43 W, we occasionally observe spontaneous parametric oscillations in the waveguide spiral (Extended Data Fig. 7), even in the absence of any input signal. Owing to the finite reflections from chip facets, amplified noise photons induce a coherent build-up, forming strong waves located at the maxima of the parametric gain lobes. A similar behaviour was recently observed in an optical fibre with single-sided Bragg reflectors59 owing to Rayleigh scattering in the fibre.

Once formed, the comb can be present for several minutes and disappears only when the coupling degrades too much. A more rigorous investigation of the observed comb formation is out of the scope of this work and will be reported elsewhere. This measurement demonstrates that our amplifier operates at or close to its internal gain limit, yet the achievable gain may be substantially improved if facet reflection is suppressed with the same methods as used in ref. 18.

Signal power sweep and noise figure measurements

To vary input signal power, we use an L-band EDFA (Keopsys CEFA-L) and a digital variable optical attenuator (DVOA; OZ Optics DA-100). These two components are installed in the signal optical path and used only for this experiment. We set the signal EDFA to the maximum achievable output power and change the attenuation of the DVOA over the entire accessible range, from 60 dB to 0 dB. For reference, we measure input signal power in the optical fibre before the OPA directly using the OSA in the absence of the pump wave (Extended Data Fig. 8a). The amplified signal at a pump power of 4.43 W is shown in Extended Data Fig. 8b. We estimate the noise figure using the following relation12,40:

$$\rmNF=\frac1G+2\frac\rho _\rmASEGh\nu ,$$

(4)

in which G is optical gain and ρASE is the noise-power density, assuming a bandwidth of 0.1 nm. We note that we use a corrected bandwidth for the measurements of the noise-power density and we account for 2.5 dB of coupling losses at each chip facet. The optical SNR of the input signal is larger than 48 dB. Hence the contribution of the input ASE noise of the signal is negligible for small input signal powers, which can be seen in Extended Data Fig. 8b; the noise-power levels for the first input signal powers are essentially the same, making it possible to directly use the corresponding value as a true value for the noise power and eliminating the need to manually correct for the input signal ASE. The degradation of the noise figure at higher signal input powers is attributed to gain saturation; in other words, the signal gain becomes weaker while the parametric fluorescence is still within the small-signal regime and undergoes a higher amplification. The signal noise here originates mostly from the L-band EDFA and noise correction at high input signal powers is tricky because of the coupling fluctuations, spectral features in the transmission function of the device, higher-order FWM processes and gain saturation, leading to different gains experienced by the signal and its noise.

Frequency-comb amplification—extended data

In Extended Data Fig. 9, we show the extended datasets for the EO comb and Kerr soliton comb amplification measurements. Note that, because of the nearly instantaneous nature of parametric amplification, we do not use a dispersive fibre compression stage during the EO comb preparation before the amplifier to avoid high signal peak powers and amplifier saturation. Because we tune the pump wavelength at each pump-power level to match the thermal drift of the spiral and to maintain good coupling, in the case of pumping with the Kerr soliton comb, the idler comb has a different frequency offset every time. The idler comb can be seen in the data for the pump powers of 1.01 W and 1.99 W, whereas—for higher powers—the offset between the OPA pump and soliton pump is almost a multiple of the comb free spectral range, and idler comb lines are located close to the signal comb lines. Further lines can be observed throughout the entire spectra and, most notably, closer to the pump; we attribute their appearance to numerous FWM processes between various interacting lines. Further lines that are located at frequencies far outside the bandwidth of the input comb arise owing to cascaded non-degenerate FWM processes.

Coherent communication

We use four different external-cavity diode lasers (TOPTICA CTL) as sources of emission in this experiment—pump, signal and two LOs near the signal and idler wavelength—to perform heterodyne measurements. The QPSK modulation format at 10 GBd symbol rate is used to encode a pseudo-random bit sequence in the signal using an IQ modulator (iXBlue MXIQER-LN-30) driven by an arbitrary waveform generator (Keysight M8195A) and a bias controller (iXBlue MBC-IQ-LAB-A1). Next, the modulated signal is transmitted to the OPA system, in which it is combined with a pump on a 10/90 fibre splitter, attenuating the signal by 10 dB. Just before the OPA, the signal power in the fibre measures 0.5 μW. We direct 10% of the OPA output to the OSA, whereas the remainder proceeds along the primary measurement path. We use a pair of filters, each containing a circulator and a fibre Bragg grating, to eliminate the residual pump in the fibre after the OPA section. These filters allow only the signal and idler to advance through the communication line, attenuated by only 4 dB as they pass through. We use a C + L edge-band WDM with a suppression ratio greater than 25 dB to split the signal and idler; we separately verified the normal operation of our WDM in the S-band. To perform measurements using a coherent receiver (Finisar CPRV2222A-LP installed in EVA-KIT CPRV2XXX), we switch between signal and idler by simply changing the LO source and plugging the corresponding fibre output of the WDM into the input of the receiver. We select the signal wavelength to be within the region of maximum gain and to be compatible with the capabilities of our equipment. The LO power levels are set to the maximum output of their respective lasers, after confirming that these values fall within the specified input range of the coherent receiver. The analogue signal from the coherent receiver is collected using a fast oscilloscope (Teledyne LeCroy SDA8Zi-A) at a sampling rate of 40 Gs s−1 (that is, four samples per symbol) and the obtained data are digitally processed using MATLAB Communications Toolbox (version 7.8 (R2022b)) and custom functions. The names of the functions are specified in parentheses below. First, the imbalance in the collected IQ data are compensated using the Gram–Schmidt orthogonalization procedure60 to ensure that the I and Q components of the signal are orthogonal, zero-mean and normalized. Next, we apply the coarse frequency offset compensation (comm.CoarseFrequencyCompensator) and use the automatic gain control (comm.AGC) to remove amplitude variations. The signal is decimated using a raised-cosine finite impulse response filter (comm.RaisedCosineReceiveFilter) with the decimation factor of 2. After this step, the timing synchronization (comm.SymbolSynchronizer) using the Gardner timing error detector is added to the data-processing algorithm to correct timing errors and the signal is decimated again, reaching one sample per symbol. We use the carrier synchronizer algorithm (comm.CarrierSynchronizer) to correct carrier frequency and phase offsets for accurate demodulation of the received signal. As a last step, we normalize the signal and equalize it using decision feedback filtering (comm.DecisionFeedbackEqualizer) with the constant modulus algorithm. To gain an understanding of the quality of the obtained constellations, we evaluate the MER43 defined as

$$\rmMER=10\log _10\left(\frac\sum _k=1^N(I_k^2+Q_k^2)\sum _k=1^N(e_k)\right),$$

(5)

in which \(e_k=(I_k-\widetildeI_k)^2+(Q_k-\widetildeQ_k)^2\) is the squared amplitude of the error vector, \(\widetildeI_k\) and \(\widetildeQ_k\) are measured in-phase and quadrature components of symbol vectors and Ik and Qk are ideal reference values (comm.MER). The MER measures the spread of the symbol points in the constellation clusters. A wider spread results in a lower MER and lower signal quality. In the absence of notable signal degradation, the average measured symbol vector for each constellation point should coincide with the ideal symbol vector. In this case, MER becomes equivalent to the constellation SNR (or symbol SNR), which is calculated in a similar way but uses the average symbol vectors instead of the ideal reference points.