It is tough for a person to find out that they have a progressive disease, especially when it threatens to rob them of their independence. With age-related macular degeneration (AMD) — the leading cause of vision loss among older people — a person faces a gradual and irreversible loss of vision, until they might no longer be able to recognize even a loved one.

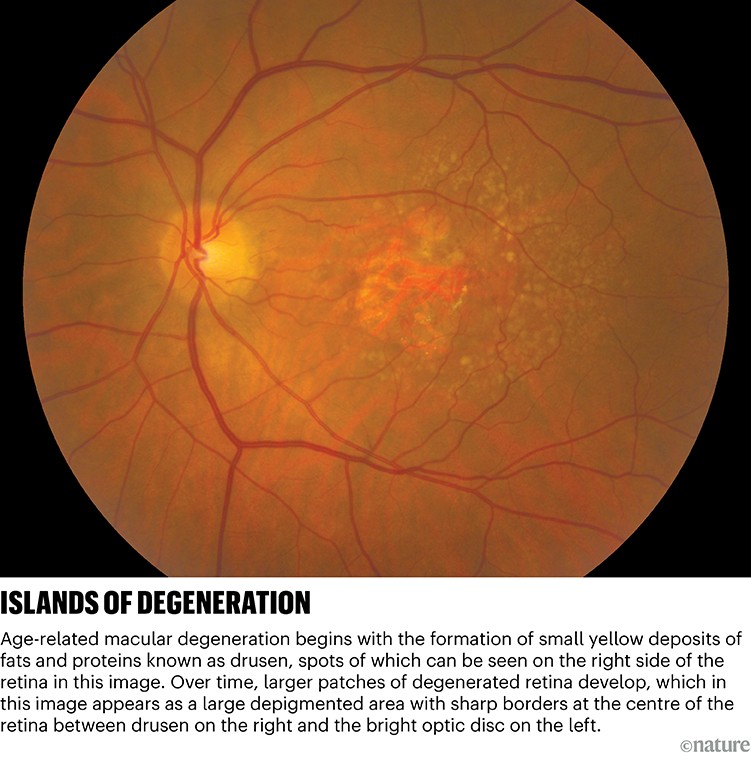

AMD affects a small region of the retina — the light-sensing tissue at the back of the eye — called the macula, which is responsible for our detailed central vision. After about the age of 50, tiny yellow deposits of proteins and fats begin to accumulate in the retina (see ‘Islands of degeneration’). To begin with, these deposits, called drusen, can pass unnoticed. But in large numbers, they contribute to a creeping spread of dysfunctional cells that can trigger early symptoms of AMD. People with AMD might notice blurriness or distortion in the central part of their vision, and might have trouble seeing when they move into low light.

The most advanced form of this condition is called geographic atrophy (GA), in which some retinal cells die off. The condition takes its name from the patches of damage on the retina, which can be seen by a physician and resemble islands on a map. Over time, these islands expand and a person’s central vision worsens.

Credit: The National Eye Institute

Until 2023, there were no therapies to stop or slow the disease. That year, two injectable drugs were approved in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to slow the progression of GA. The search for more effective interventions, however, continues. Some researchers are turning to gene therapies that could stop AMD progression with a single treatment. Others, meanwhile, are placing their hopes in cell therapy, which seeks to replace damaged or dead retinal cells to put a stop to the loss of sight — or even restore some vision to a person who has already lost it.

First steps

The retina is home to the photoreceptor cells — rods and cones — that detect light. Beneath them lies a layer of crucial support tissue, known as retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). “RPE cells provide energy to the cells, but they also help mop up after them, as photoreceptors turn over rapidly,” says Alison Clare, a biomedical researcher at the University of Bristol, UK. Degeneration of the retina often starts just outside the macula, which is only 5 millimetres in diameter. This can cause blind spots that might be noticed while reading.

As AMD progresses to GA, RPE cells die off first, followed by the rods and cones. “If you look at the different stages of the disease, you always see that RPE death precedes photoreceptor cell death,” says Kapil Bharti, a stem-cell researcher at the National Eye Institute (NEI) in Bethesda, Maryland.

Nature Outlook: Vision

Until 2023, it was difficult to treat AMD that had advanced to this stage. “Really nothing could be done,” says Tiarnán Keenan, a retinal-disease clinician at the NEI. “You might continue to see a retina specialist, or you might not, because we didn’t really have anything to offer.” This began to change with the US approval of two drugs: pegcetacoplan (marketed as Syfovre by the biotechnology company Apellis Pharmaceuticals in Waltham, Massachusetts) and avacincaptad pegol (marketed as Izervay by drug firm Astellas Pharma in Tokyo).

These advances are rooted in a growing understanding of the immune system and AMD. Drusen deposits on the retina are made up of by-products of metabolism; young people’s eyes clear them away without difficulty, but they can pile up in later life. The more drusen that accumulate, the higher the risk of developing AMD. These mounds of cellular garbage can trigger inflammation by provoking components of a chain of processes known collectively as the complement system, which is part of the innate immune system. To dial down the inflammatory response, each of the two FDA-approved drugs for GA blocks a crucial protein in the chain — C3 for Syfovre and C5 for Izervay. The benefits are modest, but appreciable: clinical trials suggest that these treatments slow down GA progression by between 12% and 27%.

Despite this, not everyone is saying yes to the new drugs. “Patients often have doubts,” says Fernando Arevelo, an ophthalmologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. Each drug has to be delivered by injection into the eyes every one to two months — “a big commitment for patients who are around 70 or 80 years old,” he says. There is also a risk of the treatment leading to further visual impairment, and of accelerating progression to another form of the disease, called wet AMD, treatment of which currently entails a different set of regular eye injections.

These challenges are compounded by the fact that people receiving the treatments might not notice any benefit. The drugs do not promise improvements in vision, but rather slow the rate of decline — a result that is much harder for an individual to appreciate. Benefits of changes in lifestyle and diet on AMD progression can be similarly difficult for people to perceive.

For people in Europe, drugs are not an option at all. In 2024, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) rejected market authorization for Syfovre. The agency did not think it offered enough benefit for individuals and highlighted safety concerns associated with the regular injections into the eye. Astellas Pharma subsequently withdrew its application for EMA approval for Izervay.

One shot

An alternative strategy that would dispense with the need for regular injections into the eye is to deploy gene therapy. The idea is to inject a viral vector that ferries a gene into the retina. That gene orders cells to manufacture a therapeutic protein. “The eye will make whatever drug is inside it, and you don’t need these monthly injections for the rest of your life,” explains Ted Leng, a researcher and clinical ophthalmologist at Stanford University’s Byers Eye Institute in Palo Alto, California. “Gene therapy can be a one and done treatment.”

Other clinicians are cautiously hopeful. “Gene therapy is promising if we can find an efficient vector which is safe and non-inflammatory, and we can produce enough therapeutic protein reliably,” says David Eichenbaum, an ophthalmologist and research director at medical practice Retina Vitreous Associates of Florida in St Petersburg. Sometimes a person’s immune system can respond destructively to even a harmless virus, therefore inflammation will need to be closely monitored, says Clare.

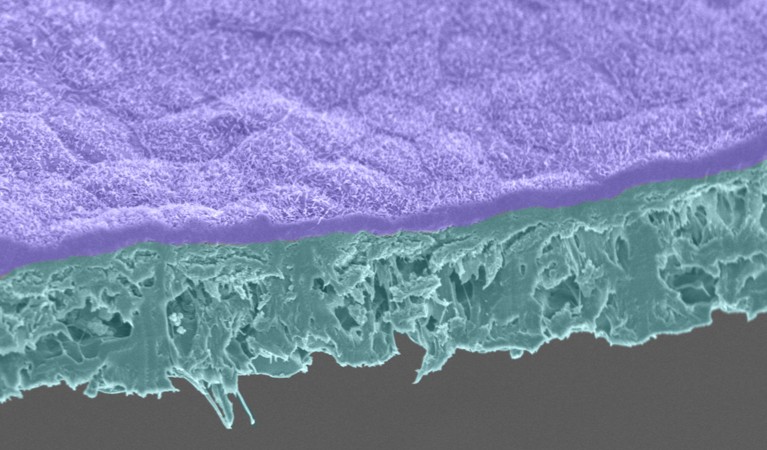

Retinal pigment epithelium cells (purple) are grown on a biodegradable scaffold (cyan).Credit: Jair Montford, Ruchi Sharma, Kapil Bharti/National Eye Institute

The pharmaceutical company Janssen Research and Development in Raritan, New Jersey, has completed a phase I trial of a gene-therapy product that is injected into the eye1. An adeno-associated virus (AAV) ferries a gene into normal retinal cells, where it expresses a naturally occurring protein called CD59. This protein inhibits the part of the complement system that would otherwise release a lethal barrage of proteins that riddles target cells with holes. Eichenbaum says the early trial results look promising from a safety perspective, and the procedure is straightforward.

The retina is an ideal target for gene therapy: not only is the eye is more accessible than many other parts of the body, but imaging is also uncomplicated. “It’s quite easy to take a picture of the back part of the eye. It’s not invasive and it takes a couple of seconds,” says Steffen Schmitz-Valckenberg, a specialist in macular and retinal diseases at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. Improvements or deterioration in patients can therefore be monitored relatively easily.

That doesn’t make development of gene therapies for the eye easy, however. In 2022, the pharmaceutical company Novartis bought UK-based Gyroscope Therapeutics to acquire its GT005 gene therapy for GA. This approach had been shown to successfully drive expression of the human complement factor C1 — a natural inhibitor of the complement system — in the eyes of mice2. But in September 2023, Novartis announced that it would stop the development of this treatment for GA following disappointing preliminary results from phase II trials.

Turn back time

Currently, both these gene therapies and the available drugs seek only to slow the loss of vision by dialling down inflammation. Yet some clinicians are daring to speak of a greater aim — restoring retinal cells that have already been lost.

One theory for the modest efficacy of complement-targeting therapies for GA so far is that it is simply too late to dampen inflammation at this stage of the disease. “This is probably important earlier in the disease, but maybe not at the later stage of GA expansion,” says Keenan. Once the disease has advanced and the RPE cells that support the photoreceptors have started to die off, stopping progression might require more drastic action.

One route could be to surgically replace lost RPE cells before the photoreceptors die off, and so maintain a person’s vision. “If we catch people with geographic atrophy in a particular window, we could implant a layer of healthy RPE that might prevent the death of these photoreceptors,” says Keenan.

Leng shares Keenan’s enthusiasm. “Studies in animal models and in patients support the notion that if you replace RPE, you can actually protect the photoreceptors,” he says. If this window is missed, replacing the photoreceptors themselves could be an option. “What gets me most excited right now is the potential of cell therapy,” Leng says. “This has the potential to not only halt the disease, but actually restore vision.”

There are a few options as to where to source these cells. Leng was involved in a safety study of people who had human stem cells from the central nervous system transplanted into their eyes to treat GA in a trial that began in 20123. Although just 15 people took part, there were hints that the disease slowed slightly. Experiments in rats have shown that these cells could survive for at least eight months and helped to preserve the animals’ photoreceptors4.

The advantage of using neural stem cells is that there is a limited range of cells that they can become, reducing the chances of them developing into a random collection of cells known as a teratoma, or going rogue and forming a tumour.

The thinking behind the original trial was partly that these cells would secrete a fertilizing milieu of growth factors that would “restore, replenish or nurture” remaining retinal cells, says Leng. It has been reported that a graft of these cells could help RPE cells in their immediate vicinity, as well as photoreceptors5. “Once they set up shop, they are a little factory producing growth factors that help support other cells,” Leng enthuses.

Leng is also involved in a trial with the firm Luxa Biotechnology in Fort Lee, New Jersey, that will see people with dry AMD receive the progeny of RPE cells harvested from the eyes of deceased donors. However, a person’s immune defences might flag such cells as foreign and target them for destruction. With this in mind, a handful of AMD researchers have generated induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells from people’s own cells, and then encouraged these shapeshifters to become RPE cells. In his laboratory, Bharti has generated RPE cells from stem cells derived from blood cells, and matured them on a biodegradable scaffold with a network of tiny blood vessels6. Meanwhile, a group in Japan has created a sheet of RPE cells from the skin of a 77-year-old woman with advanced AMD, and transplanted it into her eye. The procedure seemed to be safe, but had no impact on her vision7.

More from Nature Outlooks

Bharti’s team has transplanted cells derived from stem cells into two people; in total, more than 90 people with dry AMD have received transplants of retinal tissue. However, no such therapy has yet made it to late-stage trials, and it remains unclear which of the many strategies that are being investigated — involving various types of stem cell, differentiation protocols and delivery approaches — will work out best. “We need to launch multiple ships to find out which ones remain afloat,” says Bharti.

Bharti thinks that it will be another five to seven years before cell therapy becomes an option. “There are so many unknowns with a living drug,” he says. Cost could be an issue, especially if stem cells and the retinal cells they form must be generated from a person’s own cells. “Something like this could cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, but if you automate it, we think we could reduce the cost of manufacturing ten-fold,” says Bharti.

Another, slightly different approach to restoring vision is a technique known as optogenetic therapy. This involves providing light-sensitive molecules to surviving cells of the retina that can take over the role of lost photoreceptors. Such a strategy has achieved some positive results in people with advanced retinitis pigmentosa, a genetic disease of the retina with no known cure, and there is some hope that it could also help people with GA.

Cell and gene therapies might be some way from fruition, but the progress being made and the arrival of drugs to manage GA has given many clinicians reasons to be upbeat about the future. “I love that there is hope for geographic atrophy,” says Eichenbaum. The disease is expected to become more common as populations in Western countries get older, and this is encouraging a laser-like focus among some researchers on developing treatments. “Patients are desperate, to be honest,” says Leng. “I see people every day that are just depressed and losing their vision. That’s why I’m involved with all this exploration. I want to bring something new to patients.”