Cohort

Wild-type C57BL/6 mice were bred at Baylor College of Medicine or received from the Aged Rodent Colony at the National Institute of Aging (Baltimore, MD). C57BL/6J:FVB/NJ F1 hybrid mice were bred in the Niedernhofer laboratory at the University of Minnesota as previously described52. HET3 mice were bred at the Jackson Laboratories as described53. C57BL/6 were housed at the AAALAC-approved Center for Comparative Medicine in BSL-2 suites. Experimental procedures were approved by the Baylor College of Medicine or University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees and performed following the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare guidelines and PHS Policy on Use of Laboratory Animals. Mice were housed with the same sex in ventilated cages, under a 14/10-h light–dark cycle with temperature and humidity control and enrichment material and fed ad libitum with a standard chow diet. Female mice were chosen for internal consistency and because of their slightly longer lifespan. All mice were nulliparous.

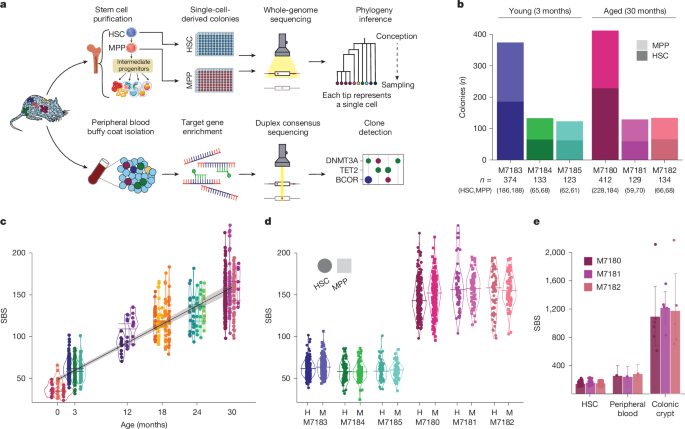

Haematopoietic progenitor purification

Whole bone marrow cells were isolated from murine hindlimbs and enriched for c-Kit+ haematopoietic progenitors prior to fluorescence-activated cell sorting using a BD Aria II and BD FACSDiva software (v.9.0). Whole bone marrow was incubated with anti-CD117 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) for 30 min at 4 °C following magnetic column enrichment (LS Columns, Miltenyi Biotec). Progenitor-enriched cells were stained with an antibody cocktail to identify specific progenitor populations using a recent consensus definition51. LSKs containing a mixture of stem and progenitor cells were defined as Lineage–c-Kit+Sca-1+ (Lineage– refers to being negative for expression of a set of lineage-defining markers indicated below). HSCs were defined as LSK+FLT-3–CD48–CD150+; MPPs were defined as LSK+FLT-3–CD48–CD150–. MPPGM was defined as LSK+FLT-3–CD48+CD150–, and MPPLy was defined as LSK+FLT-3+CD150−. The gating strategy is illustrated in Extended Data Fig. 1a. This immunophenotypic HSC population includes long-term stem cells with serial repopulating ability, whereas the MPP population is limited to short-term repopulation, as demonstrated in transplantation assays12,13,14,15,16. For sorting HSCs from newborn pups, the lineage marker Mac1 was excluded because it is known to be highly expressed on fetal HSCs54. Antibodies were c-Kit/APC, Sca-1/Pe-Cy7, FLT-3/PE, CD48/FITC, CD150/BV711, Lineage (CD4, CD8, Gr1, Mac1, Ter119)/eFlour-450 and purchased from BD Biosciences or eBioscience. All antibodies were used at 1:100 dilution for staining, except FLT-3/PE and CD150/BV71, which were used at 1:50 dilution. Flow cytometry data was analysed using FlowJo (v.10.8.1).

Single-cell haematopoietic colony expansion in vitro

Cell sorting was performed on a BD Arial II in two stages. First, HSCs and MPPs were sorted into separate tubes containing ice-cold fetal bovine serum using the ‘yield’ sort purity setting to maximize positive cells. Second, the cell populations from stage one were single-cell index-sorted into individual wells of 96-well flat-bottom tissue culture plates containing 100 µl of Methocult M3434 medium (Stem Cell) supplemented with 1% penicillin–streptomycin (ThermoFisher). No cytokine supplements were added to the base methylcellulose medium. Cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 14 ± 2 days, followed by manual assessment of colony growth. Colonies (more than 200 cells) were transferred to a fresh 96-well plate, washed once with ice-cold PBS and then centrifuged at 800g for 10 min. Supernatant was removed to 10–15 µl prior to DNA extraction on the fresh pellet. The Arcturus Picopure DNA Extraction kit (ThermoFisher) was used to purify DNA from individual colonies according to the manufacturer’s instructions; 62–88% of HSCs and MPPs produced colonies, indicating that we are sampling from representative populations in each individual compartment (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Extracted DNA from each colony was topped off with 50 µl Buffer RLT (Qiagen) and stored at −80 °C.

Laser capture microdissection

Matched colonic tissue from the three 30-month-old mice used in this study was dissected and snap-frozen at the time of bone marrow collection. Colon tissue sectioning and laser capture microdissection were performed as previously described55. In brief, previously snap-frozen colon tissue was fixed in PAXgene FIX (Qiagen) at room temperature for 24 h and subsequently transferred into a PAXgene Stabilizer for storage until further processing at −20 °C. The fixed tissue was then paraffin-embedded, cut into 10-μm sections and mounted on polyethylene naphthalate membrane slides. Staining of histology sections was done using haematoxylin and eosin as previously described9, with scans of each section captured thereafter. Individual colonic crypts were identified, demarcated and isolated by laser capture microdissection using a Leica Microsystems LMD 7000 microscope (Extended Data Fig. 1d) followed by lysis using the Arcturus Picopure DNA Extraction kit (ThermoFisher).

Whole-genome sequencing

For low-DNA-input WGS of haematopoietic colonies (from young and aged mice) and colonic crypts (from aged mice), enzymatic fragmentation-based library preparation was performed on 1–10 ng of colony DNA, as previously described55. WGS sequencing (2 × 150 bp) was performed at a median sequencing depth of 14× for haematopoietic colonies and 17× for colonic crypts on the NovaSeq platform. Reads were aligned to the GRCm38 mouse reference genome using bwa-mem. For whole-genome single-molecule (nanorate) sequencing, we used matched whole-blood genomic DNA collected from the three aged mice during tissue collection. Nanorate sequencing library preparation was performed as previously described19, followed by sequencing to 146–153× coverage on the Illumina Novaseq platform.

Somatic mutation identification and quality control in haematopoietic colonies

Single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) in each colony were identified using CaVEMan56, including an unmatched normal mouse control sample that had previously undergone WGS (MDGRCm38is). Insertions and deletions were identified using cpgPindel57. Filters specific to low-input sequencing artefacts were applied55. As variant calling used an unmatched control, both somatic and germline variants were initially called. Germline variants and recurrent sequencing artefacts were then identified using pooled information across mouse-specific colonies and filters as follows: (1) Homopolymer run filter. To reduce artefacts due to mapping errors or introduced by polymerase slippage, SNVs and indels adjacent to a single nucleotide repeat of length 5 or more were excluded. (2) Strand bias filter. Variants supported by reads only in positive or negative directions are probably artefacts. For SNVs, a two-sided binomial test was used to assess if the proportion of forward reads among mutant allele-supporting reads differed from 0.5. Any variant with significantly uneven mutant read support (cutoff of P < 0.001) and with over 80% of unidirectional mutant reads was excluded. For each indel, if the Pindel call in the originally supporting colony lacked bidirectional support, the indel was excluded. (3) Beta-binomial filter. Variants were filtered on the basis of a beta-binomial distribution across all colonies, as previously described9. The beta-binomial distribution assesses the variance in mutant read support at all colonies for a given mutation. True somatic variants are expected to be present at high VAF (approximately 0.50) in some colonies and absent in others, yielding a high beta-binomial overdispersion parameter (ρ). By contrast, artefactual calls are likely to be present at low VAF across many colonies, which corresponds to low overdispersion. The maximum-likelihood estimate of the overdispersion parameter ρ was calculated for each loci. For samples with more than 25 colonies, SNVs with ρ < 0.1 and indels with ρ < 0.15 were discarded. For samples with fewer than 25 colonies, SNVs and indels with ρ < 0.20 were discarded. (4) VAF filters. Variants with VAF significantly lower than the expected VAF for clonal samples across all mutant genotyped colonies, as assessed with a binomial test with P threshold less than 0.001, were discarded. Additionally, variants with VAF less than half the median VAF of variants that pass the beta-binomial filter were discarded. (5) Germline filter. All sites at which the aggregate VAF is not significantly less than 0.45 are assumed to be germline and discarded. The aggregate VAF is derived from the mutant read count across all colonies for a sample. The binomial test with a confidence threshold less than 0.001 was used to assess departure from germline VAF. (6) Indel proximity filter. SNVs were discarded if they occurred in ten bps of a neighbouring indel. (7) Missing site filter. Loci at which genotype information is unavailable because of poor sequencing coverage will interfere with accurate phylogeny construction. Variants that have no genotype or coverage less than 6× in over one-third of samples were discarded. (8) Clustered site filter. SNVs and indels within 10 bp of a neighbouring SNV or indel, respectively, were filtered. (9) Non-variable site filter. Sites genotyped as mutant or wild type in all colonies do not inform phylogeny relationships and are probably recurrent artefacts or germline variants, and thus were discarded.

Some colonies were excluded on the basis of low coverage or evidence of non-clonality or contamination. Visual inspection of filtered variant VAF distributions per colony was used to identify colonies with mean VAF < 0.4 or with evidence of non-clonality (Extended Data Fig. 1c).

Mutation burden estimation

Total SNV burden from WGS of individual colonies was corrected for differing depths of sequencing using a per-sample asymptomatic regression fit55 (Extended Data Fig. 1e). A linear mixed-effect model was used to estimate the rate of mutation acquisition with age, taking into account individual animals as a random effect as follows: \(\rmburden \sim \rmage+(0+\rmage| \rmsampleID)\).

We filtered nanorate sequencing calls as previously described19, with the following modifications: we excluded variants (1) mapped to the mitochondrial genome, (2) located within 15 bp of sequencing read ends or (3) observed in all duplex consensus reads, as these are probably germline events. Matched colony WGS data were used as a normal control. Mutation burdens were normalized to diploid genome size to determine the global SNV burdens.

Phylogeny construction and quality control

Phylogenetic trees were constructed on the basis of shared mutations between colonies for each mouse, as extensively described previously5,21. The steps, in brief, were as follows: (1) Create genotype matrix. Every colony has high sequencing coverage (median 14×) distributed evenly across the genome, allowing the determination of a genotype for nearly every mutated site observed across colonies. Each locus was annotated as Present, Absent or Unknown in a read-depth-specific manner. The number of unattributable sites was low, allowing precise inferences of colony interrelatedness. (2) Infer phylogenetic tree from genotype matrix. We applied the maximum parsimony algorithm MPBoot to construct phylogenetic trees from the genotype matrix. Only SNVs were used to infer tree topology, but both SNVs and indels (if any) were assigned to inferred branches using treemut. Loci with unknown genotypes in at least one-third of colonies were annotated as missing sites and not used in phylogeny inference. (3) Normalize branch lengths for differing sequencing depth and sensitivity. Branch lengths at this stage are defined by the number of mutations supporting each branch (molecular time). However, each colony has slightly different sequencing coverage, which correlates with differences in mutation detection sensitivity. Thus, we normalized branch lengths on the basis of genome coverage to correct for sensitivity differences across colonies with varying depth, as described in ref. 21 (Extended Data Fig. 1e). (4) Annotate trees with phenotype and genotype information. Each terminal branch (tip) of a tree represents a specific colony. Thus, we annotated each branch of the tree with the sampled cell phenotype (HSC versus MPP).

Tree-level checks were used to identify any discordant branch assignments and assess the validity of tree topology. Any branches supported by variants with mean VAF < 0.4 likely contained contamination by non-clonal variants and indicated that the filtering strategy (see above) was insufficient. Similarly, the branch-level VAF distributions of every colony (tip) in the tree were manually inspected to confirm supporting variants were not present in unrelated portions of the tree (topology discordance). Finally, the trinucleotide spectra of individual somatic mutations were compared between those mutations located on shared branches (that is, mutations supported by more than two colonies) and mutations only observed once and thus present on terminal branches. Mutation spectra were highly similar, indicating that mutations not shared by more than one colony were not populated by a relative excess of artefacts (Extended Data Fig. 1f).

Population size trajectories

We use the phylodyn package, which uses the density of coalescent events (bifurcations) in a phylogenetic tree to estimate the trajectory of N(t)/λ(t) over time5,20. Ultrametric lifespan-scaled trees were used to infer chronological timing. Under a neutral model of population dynamics, the phylogeny of a sample is a realization of the coalescent process. In the coalescent process, the rate of coalescent events at time t is proportional to the ratio of population size, N\((t)\), to the birth rate, λ(t) (which in the context of stem cell dynamics is the symmetric cell division rate). The sequence of intercoalescent intervals across any time interval [\(t\)1, \(t\)2] is informative about the value of the parameter ratio N(t)/λ(t) across the same time interval. We note that only with a constant cell division rate λ over time can the trajectory parameter be interpreted as a scalar multiple of the trajectory of population size N(t). Phylodyn assumes isochronous sampling and a neutrally evolving population. We overlaid separate population size trajectories for HSCs and MPPs in Fig. 3a.

Approximate Bayesian computation

We used inference from phylodynamic trajectories to inform the development of an HSC population dynamics model. Population size trajectories from phylodyn indicated two successive ‘epochs’ of exponential growth, with some variation in growth rate between epochs and a steady increase in population size over time (Fig. 3a). Given the constraint of tissue volumes, it may be implausible that the HSC population grows constantly. We reconcile this discrepancy by noting that there are very few late-in-life coalescences in our phylogenies and, as a consequence, the estimated phylodyn trajectory in late adulthood is associated with very wide credible intervals. We used a population growth model based on a linear birth–death process58 (in which a population tends to grow exponentially, subject to stochastic fluctuations), together with a fixed upper bound N on population size. The model assumed a constant birth rate λ and constant death rate ν, with the population trajectory growing at a rate λ − ν in an epoch. The shape of the trajectory of N(t)/λ(t) depends on the cell division rate parameter \(\lambda \), not only through the denominator in the ratio N(t)/λ(t), but also on λ − ν, through the tendency of the population size N(t) to grow exponentially at a rate λ − ν. In particular, if we increase the fixed upper limit N and at the same time increase the cell division rate λ, so that their ratio remains constant, the shape of the trajectory of N(t)/λ(t) will change as a consequence of the changes in the value of the parameter λ. This indicates that the parameters λ, ν, (in each epoch) and N, are all identifiable and so can be estimated separately. The identifiability of λ, ν and N are expanded on in Supplementary Note 4.

We applied Bayesian inference procedures29 to estimate the parameters (λ, ν and N) of the bounded birth–death process. We used ABC. This method first generates simulations of population trajectories and (sample) phylogenetic trees across a lifespan. Each population simulation is run with specific values for the population dynamic parameters drawn from a previous distribution over biologically plausible ranges of parameter values. The ABC method includes a rejection step that retains only those parameter values that generated simulated phylogenies resembling the observed phylogeny (as measured by an appropriate Euclidean distance). The accepted simulations constitute a sample from the (approximate) posterior distribution. Population trajectories and sample phylogenies were simulated using the rsimpop R package. Approximate posterior distributions were computed using the R package abc. We specified uniform joint prior densities for λ, ν and N that encompassed published estimates for N (population size) and λ (symmetric division rate)16,45,46,47,59: N ranged from 102 to 105 cells, λ ranged from 0.01 to 0.15 cell divisions per day, and ν ranged from 0 to \(\lambda \), such that the growth rate (λ − ν) is always positive (as observed in the phylodyn trajectories).

Our population dynamics model was a birth–death process incorporating two separate growth epochs. The first (early) epoch lasted until 10 weeks post-conception, and the second (later) epoch lasted from 10 weeks onwards and corresponded to murine adulthood. Inferences were weak for the early epoch; thus, the later epoch was used for parameter inferences. Posterior densities from the three older mice were computed using the ‘rejection’ method (Extended Data Fig. 6) and pooled to yield parameter estimates and credible intervals.

Early life polytomy analysis

The polytomies were used to estimate lower and upper bounds for the mutation rate per symmetric division during embryogenesis. The method detailed in ref. 20 was used, whereby the number of edges with zero mutation counts at the top of the tree (up to the first 12 mutations) is inferred from the number and degree of polytomies assuming an underlying tree with binary bifurcations. The mutations per division are assumed to be Poisson distributed. A maximum-likelihood range is then calculated in two steps: first, using the 95% CI of the proportion of zero length edges, with this next leading to a maximum-likelihood estimate for the Poisson rate. Sample M7183 lacked sufficient early life diversity (fewer than 10 unique lineages in 12 mutations molecular time) and was excluded.

Shared variants between blood and colonic crypts

Mutation genotype matrices (described above) were generated for colonic crypt samples at loci observed in truncal (shared) branches in the matched HSC tree. Every variant was annotated as present or absent for each colonic crypt. We applied two stages to crypt annotation. First, a crypt sample was marked positive if the given variant exceeded a per-sample minimum VAF threshold. The minimum VAF threshold was defined as half the median VAF for all pass-filter colonic crypt variants (as described above). Next, for each variant represented in at least one crypt, any remaining crypt with greater than 2 mutant allele read support was marked positive. This tiered definition allowed for shared variant capture despite differences in coverage among crypt samples. The proportion of a shared variant present among crypt samples was illustrated as a pie chart and annotated to the respective branch of the matched HSC tree (Extended Data Fig. 3).

Mutational signature analysis

We used the Hierarchical Dirichlet Process (HDP) algorithm to extract mutation signatures across aged and young HSC and MPP colony samples, following the process detailed in ref. 60. Previous work in humans has applied mutation signature extraction to SNVs found only on terminal branches of phylogenetic trees: such terminal branches displayed mutation burdens in excess of 1,000 mutations, depending on the organ. Given the low mutation burden in mouse haematopoietic colonies (terminal branch lengths spanning 30–150 mutations) and thus reduced mutational information, we used all branches with length greater than or equal to 30 mutations as input. To circumvent any bias against shared variants, branches with fewer than 30 SNVs were collapsed to a single ‘shared branch’ sample. We generated mutation count matrices for each branch, using the 96 possible trinucleotide mutational contexts as input to the R package hdp. HDP was run (1) without priors (de novo), (2) with the reference catalogue of all 79 signatures derived from the PanCancer Analysis of Whole Genomes study (COSMIC v.3.3.1) as priors or (3) with the signatures previously defined as active in mouse colon9, SBS1, SBS5, SBS18, as priors. Trinucleotide signature definitions were adjusted to mouse genome mutation opportunities before use as priors, and all prior signatures were weighted equally. Signature extraction parameters (1) and (2) produced profiles that did not resemble any existing signatures (cosine similarity < 0.9), probably because of relatively limited SNV burden in mouse colony data. Use of mouse colon signatures as prior information (3) yielded four signature components. Two signature components demonstrated high similarity to SBS1 and SBS5 (cosine > 0.9). The remaining two unknown components were deconvoluted to reattribute their composition to known signatures using the fit_signatures function from sigfit. This yielded three components with a reconstruction cosine similarity metric exceeding 0.99 for similarity to SBS1, SBS5 and SBS18, indicating these three signatures explain the majority of our data (Extended Data Fig. 4a). We surmise the final reattribution step was necessary because of the log-fold lower SNV burdens in mouse blood colonies (30–200 mutations) relative to other tissues examined in previous work (more than 1,000 mutations).

Branch signature assignment and analyses

For each mouse, we pooled the assigned SNVs into a ‘private’ or ‘shared’ category depending on whether the variant maps to a shared branch. Signature attribution to signatures SBS1, SBS5 and SBS18 was then carried out for each of these per mouse category using sigfit::fit_to_signature with the default ‘multinomial’ model. The per-branch attributions were then carried out by (1) assigning a per-mutation signature membership probability and then (2) summing these signature membership probabilities over all SNVs assigned to a branch to obtain a branch-level signature attribution proportion. The per-mutation signature probability was calculated using

$$P(\rmmutation\in \rmSig)=\fracP(\rmmutation\in \rmSig)P_(\rmmutation\in \rmSig){\varSigma _\rmSig^\prime \in \\rmSBS1,\rmSBS5,\rmSBS18\P(\rmmutation\in \rmSig\prime )P_(\rmmutation\in \rmSig\prime )}$$

where the prior probability, \(P_(\rmmutation\in \rmSig)\), is given by the mean Sigfit attribution probability of the specified signature, Sig, for the category that the mutation belongs to.

A linear mixed-effect model was used to assess the relationship between age and the signature-specific substitution burden for each colony while accounting for repeated measures. The signature-specific burdens per colony were estimated using a linear mixed model (R package lme4) with age as a random effect and mouse ID as grouping variable:

$$\rmburden_\rmsignature \sim \rmage+(0+\rmage| \rmmouseID).$$

Hidden Markov tree approach

Modelling the ancestral unobserved MPP and HSC states with a hidden Markov tree

We defined three unobservable (‘hidden’) ancestral states, EMB, HSC and MPP, and used the observed outcomes (HSC or MPP tip states) to infer the transition probabilities between these identities and the most likely sequence of cell identity transitions during life. The transitions between states are modelled by a discrete time Markov chain with one step in time representing one mutation in molecular time. We require the root of the tree, presumably the zygote, to start in the ‘EMB’ state and to stay in that state until ten mutations in molecular time. After ten mutations, the cell then has a non-zero probability of transitioning to another state given by the transition matrix M:

$$M=\left(\beginarrayccc1-p_\rmHSC- > \rmMPP & p_\rmHSC- > \rmMPP & 0\\ p_\rmMPP- > \rmHSC & 1-p_\rmMPP- > \rmHSC & 0\\ p_\rmEMB- > \rmHSC & p_\rmEMB- > \rmMPP & 1-p_\rmEMB- > \rmHSC-p_\rmEMB- > \rmMPP\endarray\right)$$

This then implies the following transition probabilities for branch u having length l(u) (excluding any overlap with molecular time less than ten mutations), starting in state i and ending in state k:

$$P_i,k(u)=(M^l(u))_i,k$$

Now, for a node that is in a specified state, the probability of descendent states is independent of the rest of the tree. This conditional independence property facilitates recursive calculation of a best path (‘Viterbi path’), the likelihood of the Viterbi path and the full likelihood of the observed phenotypes given the model. The approach is essentially an inhomogeneous special case of the approach previously described61.

Upward algorithm for determining likelihood of the observed states given M and a prior probability of root state π

The probability of the observed data descendant from a node u whose end of branch state is i is given by

$$P_u(D_u| i)=\prod _v\in \rmchildren(u)\left(\mathop\sum \limits_k=1^SP_i,k(v)P_v(D_v| k)\right)$$

where S is the number of hidden states (S = 3 in our use), and Du denotes the observed data descendant of u: that is, the observed tip phenotypes of the clade defined by u.

Initialization of terminal branches

The probability of observing a matching phenotype is assumed to be

$$P_u(\rmObserved\;\rmPhenotype\;\rmof\;u=i| i)=1-\epsilon $$

The probability of observing a mismatching phenotype, \(j\ne i\), is

$$P_u(\rmObserved\;\rmPhenotype\;\rmof\;u=j| i)=0.5\epsilon $$

The root probability \(P_\rmroot(D_\rmroot| i)\) is calculated recursively from the above, and the model likelihood is given by

$$P=\mathop\sum \limits_i=1^S\rm\pi _iP_\rmroot(D_\rmroot| i)$$

Given the two-stage cell sorting approach described above, we assume nearly error-free phenotyping and set ϵ = 10−12.

Determining the most likely sequence of hidden end-of-branch states

This Viterbi-like algorithm can be run in conjunction with the upward algorithm. Here, instead of summing over all possible states, we keep track of the most likely descendant states for each possible state of the current node u.

The quantity δu(i) is the probability of the most likely sequence of descendant states given that node u ends in state i:

$$\delta _u(i)=\prod _v\in \rmchildren(u)(\mathop\max \limits_k\\delta _v(k)P_i,k(v)\)$$

Additionally, for each node, we store the most probable child states given that u is in state i:

$$\varPsi _u,v(i)=\rmargmax_k\\delta _v(k)P_i,k(v)\$$

The tip deltas are initialized using the emission probabilities:

$$\delta _u(i)=P_u(\rmObserved\;\rmPhenotype\;\rmof\;u| i)$$

The above provides a recipe for recursively finding δroot(i) and is combined with prior root probability π to give the most likely root state, maxkδroot(i); in our case, we set the prior probability of ‘EMB’ to unity, so EMB is the starting state. The child node states are then directly populated using Ψ.

Targeted duplex-consensus sequencing

Genomic DNA from freshly collected peripheral blood was purified using the Zymo Quick-DNA Miniprep Plus kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 1,650 ng of high-molecular-weight DNA was ultrasonically sheared to an average 300 bp fragment size using a Covaris M220 and ligated to duplex identifier sequencing adaptors62 using the Twinstrand Biosciences DuplexSeq library prep kit. A large input of gDNA was used to ensure that the number of input genomic equivalents (about 275,000–330,000 genomes) did not limit the achievable duplex sensitivity. A custom baitset of biotinylated probes was used to enrich sequences targeting mouse orthologues of common human clonal haematopoiesis driver genes over two overnight hybridization reactions. Our target panel spanned 61.8 kb and captured homologous regions from the entire coding region of the following genes: Dnmt3a, Tet2, Asxl1, Trp53, Rad21, Cux1, Runx1, Bcor and Bcorl1 and specific exons with hotspot mutations (as observed in COSMIC) for the following genes: Ppm1d, Sf3b1, Srsf2, U2af1, Zrsr2, Idh1, Idh2, Gnas, Gnb1, Cbl, Jak2, Ptpn11, Brcc3, Nras and Kras. Targeted loci encompass more than 95% of human clonal haematopoiesis events63 and are described in Supplementary Data 2. Libraries were sequenced on the NovaSeq platform to a raw depth between 1 and 3 million reads, corresponding to duplex-consensus depths between 30,000 and 50,000× that vary across targeted exons. Quality control of duplex sequencing is discussed in Supplementary Note 3.

Variant identification in targeted gene duplex-consensus sequencing

Duplex-consensus and single-strand consensus reads were generated using the fgbio suite of tools according the fgbio Best Practices FASTQ to Consensus Pipeline Guidelines (https://github.com/fulcrumgenomics/fgbio/blob/main/docs/best-practice-consensus-pipeline.md). To build a duplex-consensus read, we required at least three reads in each supporting read family (that is, at least three sequenced polymerase chain reaction duplicates of matched top and bottom strands from an original DNA molecule). The ‘DuplexSeq Fastq to VCF’ (v.3.19.1) workflow hosted on DNANexus was also used to generate duplex-consensus reads. Next, VarDict64 was used to identify all putative variants, followed by functional annotation using Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor65. Finally, numerous post-processing filters were applied to remove false positives and artefactual variants: (1) Quality flag filter. VarDict annotates all variants using a series of quality flags that assess mapping and read-level fidelity64. Any variant with a quality flag other than ‘PASS’ was discarded. (2) Read support filter. Duplex sequencing enables detection of somatic variants even from a single read62; however, variants supported by a consensus read (singletons) were found to be highly enriched for spurious calls. Thus, any variant supported by a single read was discarded. (3) Mismatches per read filter. Variants were excluded if the mean number of mismatches per supporting read exceeded 3.0. (4) End repair and A-tailing artefact filter. Library preparation enzymatic steps may introduce false-positive SNVs near read ends due to misincorporation of adenine bases during A-tailing or mistemplating during blunting of fragmented 3′ ends. The fgbio FilterSomaticVcf tool was used to assess the probability that any variant within 20 bp of read ends was due to such enzymatic errors; probable end-repair artefacts were discarded. (5) Read position filter. Variants in positions less than or equal to 15 bp from the 5′ or 3′ end of a consensus read were observed to be enriched for spurious variants based on trinucleotide signature and were discarded. (6) Oxidative damage filter. Mechanical fragmentation (prior to duplex adaptor attachment) creates oxidative DNA damage, often in the form of 8-oxoguanine66,67, which mispairs with thymine and is fixed after polymerase chain reaction amplification. Any variants fitting the previously described oxidative artefact signature (SBS45) were discarded. (7) Sequencing coverage filter. Variants at loci with duplex depth of less than or equal to 20,000× were considered undersequenced and discarded. (8) Strand bias filter. We used a Fisher’s exact test to assess for forward or reverse strand bias between wild-type and mutant reads. Any variant enriched for unidirectional read support was discarded. (9) Recurrent variant filter. Variants present in 5% or more of samples per duplex-sequencing batch or in five or more independent samples were discarded. (10) Indel length filter. Long insertions or deletions could be attributed to poor mapping, erroneous fragment ligation or false-positive calls by VarDict. Any indels greater than or equal to 15 bp were excluded. (11) High-VAF filter. Germline variants display a VAF of 0.5 or 1.0. Any variants with VAF 0.4 or more were excluded as putative germline variants. (12) Impact filter. Clonal haematopoiesis is driven by functional coding sequence changes in driver genes. Thus, synonymous mutations were excluded during generation of the dot-plots in Fig. 4 and Extended Data Fig. 10c. This filter was not used for analyses that require synonymous variant information (dN/dS, fitness effect estimation). (13) Homologous position filter. Residues conserved with humans are likely to be functional in mice. Variants at loci without a matching reference allele at homologous position in humans were discarded. This filter primarily eliminated intronic variants and was not used for analyses incorporating synonymous variant information. Variants identified are detailed in Supplementary Data 2.

Murine perturbation experiments

Perturbation experiments were initiated in aged (21-month) male and female mice unless otherwise described. Mice were randomly allocated to control or experimental groups. Investigators were not blinded to the group assignment during experiments. For Mycobacterium avium infection, mice were infected with 2 × 106 colony-forming units of M. avium delivered intravenously as previously described68. Infected and uninfected control mice were housed in a BSL-2 biohazard animal suite following infection. Mice were infected once every 8 weeks (twice in total) to ensure chronic infection. For cisplatin exposure, mice were exposed to 3 mg kg−1 cisplatin delivered intraperitoneally every 4 weeks, as indicated. Dose spacing was selected to allow for sufficient recovery following myeloablation and blood counts were not altered in cisplatin-treated mice (Fig. 4c), indicating recovery of haematopoiesis. For 5-fluorouracil exposure, 150 mg kg−1 5-FU was delivered intraperitoneally every 4 weeks two times; this 5-FU dose has previously been shown to drive temporary activation of HSCs in mice69,70. Exposure to an NME of murine transmissible pathogens was performed as previously described71. In brief, immune-experienced ‘pet store’ mice were purchased from pet stores around Minneapolis, MN. Aged (24-month) C57BL/6J:FVB/NJ laboratory mice were either directly cohoused with pet store mice or housed on soiled (fomite) bedding collected from cages of pet store mice. Mice were exposed to continuous fomite bedding for 1 month, followed by 5 months recovery on specific pathogen-free bedding before tissue collection. All NME work was performed in the Dirty Mouse Colony Core Facility at the University of Minnesota, a BSL-3 facility. Age-matched C57BL/6J:FVB/NJ F1 laboratory mice maintained in specific pathogen-free conditions were used as controls. For monitoring, peripheral blood (about 50 µl) was collected in EDTA-coated tubes and analysed on an OX-360 automated hemocytometer (Balio Diagnostics). For all aforementioned mouse cohorts, peripheral blood genomic DNA was purified and converted to duplex sequencing libraries as described above.

Differences in clone burden between control and treated cohorts was quantified using a Mann–Whitney test on cumulative VAFs per sample. Gene-level enrichment was measured using a Mann–Whitney test on the maximum VAF for a given gene per sample, normalized for coverage differences between samples. Gene-level dN/dS estimates were generated as described below.

dN/dS analysis

dN/dS can be used to assess for selection within somatic mutations by comparing the observed dN/dS to that expected under neutral selection. We use the R package dNdScv72 to estimate dN/dS ratios of somatic mutations derived from whole-genome and targeted-gene duplex-consensus sequencing. To incorporate mouse-specific differences in trinucleotide context composition and background mutation rates, we generated a murine reference CDS dataset using the buildref function and genome annotations in Ensembl (v.102). For the phylogenetic trees, we input all tree variants to the dndscv function. dN/dS output and all coding variants detected in trees are listed in Supplementary Data 1. To examine dN/dS in targeted duplex-consensus sequencing data, we pooled all variants observed in cross-sectionally sampled mice across ages and ran dndscv limited to exons only included on our targeted panel (Supplementary Data 2).

Targeted capture of tree variants

We designed a custom targeted DNA baitset (Agilent SureSelect) targeting mutations on the phylogenetic trees of the aged mice and then queried genomic DNA purified from matched peripheral blood for tree-specific mutations using high-depth targeted sequencing. The baitset was designed to capture mutations on the phylogenetic trees of all three aged mice (MD7180, MD7181 and MD7182) and to cover mutations found in HSCs, MPPs and LSKs. The baitset was designed as follows: (1) All variants on shared branches that pass the SureDesign tool’s ‘moderately stringent filters’. (2) All variants on a random subset of private branches that pass SureDesign’s ‘most stringent filters’. Approximately 25% of the private branches of each mouse were randomly selected. (3) The exons and 3′ and 5′ UTRs for all clonal haematopoiesis driver genes used in our duplex sequencing panel (listed above). Target-enriched libraries were generated according to the manufacturer’s protocol and sequenced using the Illumina Novaseq platform. Baits were sequenced to median depths of 2,616×, 2,549× and 2,628× for MD1780, MD7181 and MD7182, respectively.

To quantify the degree of HSC and MPP contribution to peripheral blood, we estimated the posterior distribution of true VAF for every mutation captured with our targeted baitset. This was done using the Gibbs sampling method previously developed73. Then, for each molecular time t and for each branch that overlaps t, we estimate the VAF of a hypothetical mutation at time t. This is done by arranging our baitset variants in descending estimated VAF order at equally spaced intervals down the branch and then linearly interpolating the VAF at time t based on the estimated VAF of the neighbouring mutations. The aggregate VAF at time t for a tree or lineage is then calculated as the sum of the estimated VAFs of the overlapping branches at time t.

Maximum-likelihood estimates of fitness effects

Evolutionary framework

To generate estimates of fitness effects, mutation rates and population size, we applied an evolutionary framework based on continuous time branching for HSCs, as previously reported36. The framework is based on a stochastic branching model of HSC dynamics, where variants with a variant-specific fitness effect, s, are acquired stochastically at a constant rate μ. Synonymous and non-synonymous mutations detected with duplex sequencing in untreated 24- to 25-month-old mice were used in the analysis. Synonymous and non-synonymous mutations were considered independently. Synonymous mutations are assumed to have no fitness effect and reflect behaviour under neutral drift, whereas non-synonymous mutations were hypothesized to reflect behaviour under a positive selective advantage. The density of variants declined at VAF 5 × 10−5, so to only include VAF ranges supported by informative variants, only variants above this threshold were included in maximum-likelihood estimations described below.

How the distribution of VAFs predicted by our evolutionary framework changes with age (t), the variant’s fitness effect (s), the variant’s mutation rate (μ), the population size of HSCs (N) and the time in years between successive symmetric cell differentiation divisions (τ) is given by the following expression for the probability density as a function of l = log(VAF):

$$\rho (l)=\frac\theta (1-2e^l)e-\frace^l\varphi (1-2e^l)\,\rm\textwhere\,\theta =N\tau \mu \,\mathrmand\,\varphi =\frace^st-12N\tau s$$

The value of \(\varphi =\frace^st-12N\tau s\) is the typical maximum VAF a variant can reach and this increases with fitness effect (s) and age (t). To reach VAFs greater than φ requires a variant to both occur early in life and stochastically drift to high frequencies, which is unlikely. Therefore, the density of variants falls off exponentially for VAFs greater than φ. For neutral mutations (s = 0),

$$\varphi =\fract2N\tau $$

Because the mouse age t is known and the neutral φ is measurable from the data, the ratio φ/t allows us to infer Nτ from the distribution of neutral mutation VAFs. Because the neutral θ is measurable from the data and θ = Nτμ, we can also infer the neutral mutation rate (μ).

Probability density histograms, as a function of log-transformed VAFs, were generated using Doane’s method for log(VAF) bin size calculation. Densities were normalized by the product of bin sample size and width. Estimates for Nτ and μ were inferred using a maximum-likelihood approach, minimizing the L2 norm between the cumulative log densities and the predicted densities. For synonymous mutations, maximum-likelihood estimates were optimized for Nτ and μ. For non-synonymous mutations, variants with VAFs below the observed maximum synonymous VAF (1.99 × 10−4) were used—these variants are in the ‘neutral’ range—and estimates were optimized for with the Nτ estimated from synonymous mutations.

Differential fitness effects

We estimated the distribution of fitness effects across non-synonymous variants using our derived estimates of Nτ and non-synonymous μ. We parameterized the distribution of fitness effects using an exponential power distribution, which captures a strongly decreasing prevalence of mutations with high fitness:

$$\mu _\rmnon \mbox- \rmn\rme\rmu\rmt\rmr\rma\rml(s)\propto \exp \left[-\left(\fracsd\right)^\beta \right]$$

The shape of the distribution was fixed to β = 3 (ref. 74). Using the VAF density histograms from non-synonymous variants, we estimated the scale of the distribution and non-neutral mutation rate: \(\int _s=0^\infty \mu _\rmn\rmo\rmn\text-\rmn\rme\rmu\rmt\rmr\rma\rml(s)ds\). The maximum-likelihood fit predicted a scale of about d = 2 and the proportion of non-neutral non-synonymous mutations to be about 12% (Fig. 5b).

Statistics and reproducibility

For all presented data, the sample size n represents the number of biologically independent samples. Individual data points are displayed and represent independent biological replicates. For whole-genome-sequence experiments, colonies from at least three independent biologically replicate mice were queried at each age timepoint. For duplex experiments, each individual mouse queried is an independent biological replicate. In perturbation experiments, displayed data are aggregated from at least two independent replicate treatment cohorts. Mice were randomly allocated to control or experimental groups. Investigators were not blinded to the group assignment during experiments. Replicate experiments were designed identically. All replicate experiments were successful. All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, v.10) or R (v.4.3) unless otherwise specified. The statistical tests used are detailed in the figure legends. Measure of centre and error bars are described in the figure legends.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.