Plant material, phenotypic analyses and imaging

Details on all plant material used in this study, including the passport identification numbers of acquisitions from seed stock centres, are available in Supplementary Tables 1 and 10. All phenotypic assessments were performed on plants grown in greenhouses or fields. All of the images presented in all of the figures were taken by the authors and are our own. All illustrations (such as fruit representations) in all of the figures were prepared by the authors and are our own. Quantitative phenotypic data were collected manually in fields and greenhouses and recorded in Microsoft Excel. Source data are provided in Supplementary Tables 8, 12–14, 16 and 18. Seven herbarium vouchers were collected from field-grown Solanum accessions. Vouchers were deposited to the Steere Herbarium at the New York Botanical Garden (Supplementary Table 1).

Tissue collection and high-molecular-mass DNA extraction

For extraction of high-molecular-mass DNA, young leaves were collected from 21-day-old light-grown seedlings. Before tissue collection, seedlings were etiolated in complete darkness for 48 h. Flash-frozen plant tissue was ground using a mortar and pestle and extracted in four volumes of ice-cold extraction buffer 1 (0.4 M sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 10 mM MgCl2 and 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol). Extracts were briefly vortexed, incubated on ice for 15 min and filtered twice through a single layer of Miracloth (Millipore Sigma). Filtrates were centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C, and pellets were gently resuspended in 1 ml of extraction buffer 2 (0.25 M sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 10 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, and 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol). Crude nuclear pellets were collected by centrifugation at 12,000g for 10 min at 4 °C and washed by resuspension in 1 ml of extraction buffer 2 followed by centrifugation at 12,000g for 10 min at 4 °C. Nuclear pellets were resuspended in 500 ml of extraction buffer 3 (1.7 M sucrose, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 0.15% Triton X-100, 2 mM MgCl2 and 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol), layered over 500 ml extraction buffer 3 and centrifuged for 30 min at 16,000g at 4 °C. The nuclei were resuspended in 2.5 ml of nuclei lysis buffer (0.2 M Tris pH 7.5, 2 M NaCl, 50 mM EDTA and 55 mM CTAB) and 1 ml of 5% Sarkosyl solution and incubated at 60 °C for 30 min.

To extract DNA, nuclear extracts were gently mixed with 8.5 ml of chloroform:isoamyl alcohol solution (24:1) and slowly rotated for 15 min. After centrifugation at 4,000 rpm for 20 min, 3 ml of aqueous phase was transferred to new tubes and mixed with 300 ml of 3 M NaOAc and 6.6 ml of ice-cold ethanol. Precipitated DNA strands were transferred to new 1.5 ml tubes and washed twice with ice-cold 80% ethanol. Dried DNA strands were dissolved in 100 ml of elution buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5) overnight at 4 °C. The quality, quantity and molecular mass of DNA samples were assessed using Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific), Qubit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (CHEF Mapper XA System, Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Genome assembly

Reference quality genome assemblies for each of the 22 species (and two reference quality genomes for S. muricatum) (accession information is provided in Supplementary Table 2) were generated using a combination of long-read sequencing (Pacific Biosciences) for contigging and optical mapping (Bionano Genomics) for scaffolding. Between 1 and 4 PacBio Sequel IIe flow cells (Pacific Biosciences) were used for the sequencing of each sample in the Solanum wide pan-genome (average read N50 = 29,067 bp, average coverage = 63×). The exact number of flow cells and sequencing technology for each sample are provided in Supplementary Table 2. For the additional nine S. aethiopicum samples, a combination of PacBio Sequel IIe, PacBio Revio sequencing and Oxford Nanopore sequencing was used to assemble the genomes (Supplementary Table 11). Before assembly, we counted k-mers from raw reads using KMC362 (v.3.2.1) and estimated the genome size, sequencing coverage and heterozygosity using GenomeScope (v.2.0)63. For five samples (details are provided in Supplementary Table 2), low-quality reads were filtered out with a custom script (https://github.com/pan-sol/pan-sol-pipelines). Sequencing reads from each sample were assembled using hifiasm64 and the exact parameters and software version varied between the samples based on the level of estimated heterozygosity and are reported in Supplementary Table 2. After assembly, the draft contigs were screened for possible microbial contamination as previously described26. Nchart was generated with ggplot2 (https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/) using adaptation of N-chart (https://github.com/MariaNattestad/Nchart).

Genome assembly scaffolding

Optical mapping (Bionano Genomics) was performed for 17 samples to facilitate scaffolding. Scaffolding with optical maps was performed using the Bionano solve Hybrid Scaffold pipeline with the recommended default parameters (https://bionano.com/software-downloads/). Hybrid scaffold N50s ranged from 33,254,022 bp to 219,385,699 bp (further details, including Bionano molecules per sample, are provided in Supplementary Table 2). High-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) from Arima Genomics was performed for eight samples to finalize scaffolding. With Hi-C, reads were integrated with the Juicer (v.0.7.17-r1198-dirty) pipeline. Next, misjoins and chromosomal boundaries were manually curated in the Juicebox (v.1.11.08) application. Chromosomes were named based on sequence homology, determined using the RagTag65 scaffold (v.2.1.0, default parameters), with the phylogenetically closest finished genome (Supplementary Table 2), 12 of these samples (including nine S. aethiopicum samples) were scaffolded with Ragtag. Finally, small contigs (<50,000 bp) with >95% of the sequence mapping to a named chromosome were removed. Moreover, small contigs (<100,000 bp) with >80% of the sequence mapping to a named chromosome that contained one or more duplicated BUSCO genes, but no single BUSCO genes, were also removed using a Python script. Using merqury61 with the HiFi data, the final consensus quality of the assemblies was estimated as QV = 53 on average and a completeness of 99.2741% on average.

Tissue collection, RNA extraction and quantification

All tissues were collected in 3–4 biological replicates from different greenhouse-grown plants at approximately 09:00–10:00 and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen in 1.5 ml microfuge tubes containing a 5/32 inch (about 3.97 mm) 440 stainless steel ball bearing (BC Precision). Tubes containing tissue were placed in a −80 °C stainless steel tube rack and ground using a SPEX SamplePrep 2010 Geno/Grinder (Cole-Parmer) for 1 min at 1,440 rpm. For shoot apices, total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions for ground tissue. For all other tissues (cotyledons, hypocotyls, leaves, flower buds and flowers), total RNA was extracted using Quick-RNA MicroPrep Kit (Zymo Research). RNA was treated with DNase I (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The purity and concentration of the resulting total RNA was assessed using the NanoDrop One spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Libraries for RNA-seq were prepared using the KAPA mRNA HyperPrep Kit (Roche). Paired-end 100 base sequencing was conducted on the NextSeq 2000 P3 sequencing platform (Illumina). Reads were trimmed using trimmomatic (v.0.39)66 and then mapped to their respective genome using STAR (v.2.7.5c)67 and expression was computed in TPM.

Gene annotation

The gene-annotation pipeline (Supplementary Fig. 2c) involved several crucial steps, beginning with lift over of gene models using the Liftoff algorithm on community-established references of tomato (Heinz reference genome) and eggplant (Brinjal reference genome). We augmented the annotation using RNA-seq data from 15 species and multiple tissues for de novo annotation. Initially, the quality of raw RNA-seq reads from each sample (Supplementary Table 6) underwent assessment using FastQC v.0.11.9 (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). Subsequently, reference-based transcripts were generated using the STAR (v.2.7.5c)67 and Stringtie2 (v.2.1.2)68 workflows. To refine the data, invalid splice junctions from the STAR aligner were filtered out using Portcullis (v.1.2.0)69. Orthologues with coverage above 50% and 75% identity were lifted from the tomato reference genome Heinz (v.4.0)70 and the eggplant reference genome Eggplant (v.4.1)71 using Liftoff (v.1.6.3)72 using the parameters –copies,–exclude_partial and using both the Gmap (v.2020-10-14)73 and Minimap2 (v.2.17-r941)74 aligners. Furthermore, protein evidence from several published Solanaceae genomes70,71,75, and the UniProt/SwissProt database were used to support gene annotation. Structural gene annotations were generated using the Mikado (v.2.0rc2)76 framework, leveraging evidence from the Daijin pipeline. Moreover, microsynteny and shared orthology to Heinz v.4.0 and Eggplant v.4.0 were assessed using Microsynteny and Orthofinder (v.2.5.2)77. Correction of gene models with inframe stop codons was performed using Miniprot278 protein alignments to incorporate protein data from Heinz v.4.0 and Eggplant v.4.1. Furthermore, gene models lacking start or stop codons were adjusted by placing them within 300 bp of the nearest codon location using a custom Python script (https://github.com/pan-sol/pan-sol-pipelines). Overall gene synteny was visualized using GENESPACE (v.1.3.1)79.

For functional annotation, ENTAP (v.0.10.8)80 integrated data from diverse databases such as PLAZA dicots (v.5.0)81, UniProt/Swissprot82, TREMBL, RefSeq, Solanaceae proteins and InterProScan583 with Pfam, TIGRFAM, Gene Ontology and TRAPID84 annotations. Finally, the annotated data underwent a series of filtering steps, excluding proteins shorter than 20 amino acids, those exceeding 20 times the length of functional orthologues and transposable element genes, which were removed using the TEsorter85 pipeline.

We assessed the completeness of the gene models by assessing single-copy orthologues through BUSCO86 in protein mode, comparing them against the solanales_odb10 database (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). Moreover, we examined the presence or absence of a curated set of 150 candidate genes known to be relevant in plant development and QTL studies (Supplementary Table 7).

Transposable element annotation

The S. lycopersicum chloroplast and mitochondrion sequences were collected from NCBI reference sequences NC_007898.3 and NC_035963.1, respectively. Non-transposable-element repeat sequences, including 18S rDNA (OK073663.1), 5S rDNA (X55697.1), 5.8S rDNA (X52265.1), 25S rDNA (OK073662.1), DNA spacer (AY366528.1), centromeric repeat (JA176199.1) and telomere sequences (TTTAGGG), were collected from the NCBI and further curated. Transposable element sequences curated in the SUN locus study87 as well as several other transposable element sequences from NCBI were also collected. These sequences were combined as the curated set of tomato repeats.

De novo transposable element annotation was first performed on each genome using EDTA (v.2.1.5)88, with coding sequences from the ITAG4.0 Eggplant V4 annotation89 provided (–cds) to purge gene coding sequences in the transposable element annotation and parameters of –anno 1 –sensitive 1 for sensitive detection and annotation of repeat sequences. Curated tomato repeats were supplied to EDTA (–curatedlib) for de novo annotation. Transposable element annotations of individual genomes were together processed by panEDTA90 for the creation of consistent pan-genome transposable element annotation. The summary of whole-genome repeat annotations was derived from .sum files generated by panEDTA (Supplementary Table 4).

Evaluation of repeat assembly quality was performed using LAI (b3.2)91 with inputs generated by EDTA and parameters -t 48 -unlock. LAI of S. aethiopicum genomes were standardized based on the HiFi-based reference assembly, with the parameters -iden 95.71 -totLTR 49.22 -genome_size 1102623763 -t 48 -unlock.

Generation of CRISPR–Cas9-induced mutants

CRISPR guide RNAs to target CLV3 and SCPL25 across Solanum species were designed using Geneious (listed in Supplementary Table 20). The Golden Gate cloning approach was used to create multiplexed gRNA constructs. Plant regeneration and Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of S. prinophyllum were performed according to our previously published protocol92. For S. cleistogamum plant regeneration, the medium was supplemented with 0.5 mg l−1 zeatin instead of 2 mg l−1 and, for the selection medium, 75 mg l−1 kanamycin was used instead of 200 mg l−1. For S. aethiopicum, the protocol was the same as for S. cleistogamum, except the fourth transfer of transformed plantlets was done onto medium supplemented with 50 mg l−1 kanamycin. The seed germination time in culture can vary between species and batches of harvested seeds. Typically, S. prinophyllum germination took 8–10 days, S. cleistogamum germinated in 6–8 days and S. aethiopicum in 7–10 days.

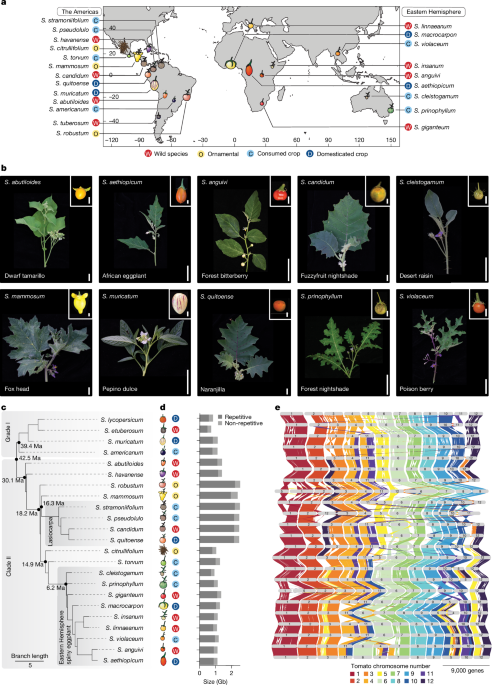

Distribution maps and species status

Species were categorized into wild, domesticated, locally important consumed or ornamental based on taxonomic literature and expert opinion17 (PBI Solanum Project (2024), Solanaceae Source; http://www.solanaceaesource.org/). The distribution maps were generated using the open source osm-liberty package (http://github.com/maputnik/osm-liberty/). Native ranges were derived from the same taxonomic literature and approximate centroids of the ranges were used for the mapping. The map is from osm-liberty, designed for open source maps.

Phylogenomic analyses

Jaltomata sinuosa93 was used as an outgroup for the Solanum pan-genome tree, whereas the closely related S. anguivi, S. insanum and S. melongena were used as an outgroup for the S. aethiopicum dataset. Orthofinder77 was used to identify single-copy orthologues across all species. This resulted in 7,825 loci for the Solanum pan-genome dataset, and 19,769 loci for the S. aethiopicum dataset. To reduce the computing time, we randomly subsampled 5,000 loci for the S. aethiopicum dataset. This strategy was validated by topology, bootstrap support and gene tree concordance factors that are nearly identical to results obtained from a smaller 353 loci dataset described previously35. To reduce the effect of missing data and long branch attraction, sequences shorter than 25% of the average length for each loci were eliminated as described previously35. MAFFT94 was used to align each locus individually. Only loci that had all species in the alignment were retained. trimAl was also used to remove columns that had more than 75% gaps. IQ‐TREE2 (ref. 95) was used to generate individual ML trees for each locus. The resulting phylogenies were used for coalescent analyses with ASTRAL‐III (v.5.7.3)96, where tree nodes with <30% BS values were collapsed using Newick Utilities (v.1.5.0)97. Branch support was assessed using localPP support98, where PP values > 0.95 were considered strong, 0.75 to 0.94 weak to moderate, and ≤0.74 as unsupported. Trees were visualized with R using the packages ggtree99 and treeio100.

The 22 Solanum species were distributed into two major clades, grade I and clade II, along an orthologue-based phylogenetic tree. The terms grade I and clade II are established clade names in Solanum, originating from reference phylogenetic publications35. These were formally referred to as clade I and clade II, but clade I was shown to consist of a set of paraphyletic clades that do not form a monophyletic group. Thus, they are now referred to as grade I to reflect their evolutionary origin.

Gene expansion contraction analysis

To analyse gene expansions and contractions, we processed the ultrametric species tree and gene family counts from OrthoFinder using CAFE5 (ref. 101). CAFE5 was run with the gamma model and parameter ‘k = 3’ to identify changes in gene family size along the species tree while accounting for rate variation among gene families.

GO enrichment analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed using the GOATOOLS package102 to investigate the functional implications of genes associated with various duplication types including whole-genome (WGD), tandem (TD), proximal (PD), transposed (TSD) and dispersed (DSD) duplications. Genes were classified into these different duplication categories by DupGen_finder38. Moreover, we conducted GO enrichment on gene expansions (Supplementary Table 21) and contractions (Supplementary Table 22) identified across all lineages as reported by CAFE5, to examine functional trends related to these gene copy-number changes across the pangenome.

Synteny analysis

The genomic neighbourhood around CLV3 for selected species was manually inspected to detect and annotate intact and pseudogenized CLV3 copies using pairwise sequence comparison with Exonerate (www.ebi.ac.uk/about/vertebrate-genomics/software/exonerate). Synteny plots were generated from a reciprocal BLASTP table obtained running Clinker (v.0.0.29, github.com/gamcil/clinker). Pseudomolecule visualization was generated via a custom script (https://github.com/pan-sol/pan-sol-pipelines). Transposable elements and resistance genes annotations were overlaid as needed using custom scripts (https://github.com/pan-sol/pan-sol-pipelines).

Gene expression analysis

Reads from each tissue sample were aligned to the corresponding species-specific genome using STAR (v.2.7.2b)67, and only samples with more than 50% uniquely mapped reads were retained for subsequent analysis. For each species with two or more biological replicates per tissue, we calculated the Spearman correlation between tissue replicates, and removed samples with low correlation (0.75 or below). This yielded gene expression estimates for 240 samples across 22 species, with 15 species having expression data in two or more tissues. Specifically, 7 out of 22 species had expression data exclusively from the apex tissue, while 15 species had expression from two or more tissues. As expression diversification groups are defined based on the coexpression and expression fold change of paralogue pairs across two or more tissues, the analyses focused on 15 out of 22 species. Expression data were TPM-normalized and genes with zero expression across all of the samples were excluded from further analysis. PCA was performed on the tissue-specific expression profiles of 5,146 singleton genes selected based on Orthofinder results and shared across all 22 species to reveal the global relationships among samples. Plotting was performed using ggplot2 (https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/). This validated the expected results that expression was largely clustering by tissue type.

Analysis of whether the total dosage of duplicate gene pairs is conserved across Solanum

Survival of a gene after duplication depends on the competition between preservation to maintain partial or total dosage and mutational degradation rendering one copy with reduced or no function. Consequently, functional fates of duplicate genes are often characterized by the extent of selective pressures on total dosage. To assess the relative importance of dosage balance (copies evolving under strong purifying selection to maintain total dosage) and neutral drift (no selection on total dosage) in maintaining duplicate genes, we compared the total expression of paralogue pairs within each tissue for each pair of species. Note that the prickle tissue from S. prinophyllum is not included in this analysis as it is absent in the other 21 species.

In each tissue, gene expression was averaged over the biological replicates for each species. For each pair of species with expression data in a shared tissue, orthogroups with exactly two copies in each species with non-zero average expression in the tissue were retained for further analysis. For each tissue and species pair, we calculated the summed expression of paralogue pairs in each retained orthogroup, and observed that the total orthogroup-level expression was highly correlated across species, suggesting a prominent role of dosage balance in shaping the expression evolution of paralogues. We computed the ratio of the orthogroup-level expression between the species pair and transformed them into z scores. For each orthogroup in a species expressed in the tissue of interest, we averaged the P values from all pairwise species comparisons, adjusted the average P values using Benjamini–Hochberg correction and classified orthogroups with an adjusted average P < 0.05 as dosage-unconstrained orthogroups. All other orthogroups in the species and tissue were assumed to be evolving under constraint on total dosage.

All other orthogroups were assumed to evolve under selective constraint on total dosage. Note that the high z-score threshold provides a conservative estimate of the number of paralogue pairs evolving under drift. Sequence evolution rates for paralogue pairs (Ka/Ks) were calculated using KaKs_Calculator (v.2.0)103.

Different modes of paralogue functional evolution

For each of the 15 species in which expression data were collected for two or more tissues, the expression data were first subset to genes with greater-than-median expression in at least one sample. The coexpression network for each species was constructed by calculating the Pearson correlation between all pairs of genes, ranking the correlation coefficients for each gene (with NAs assigned the median rank) and then standardizing the network by the maximum ranked correlation coefficient. From OrthoFinder, we obtained 763,492 paralogue pairs across the 15 species, representing all combinations of gene pairs within orthogroups. Of these pairs, 71% had low or no expression, and another 15% were filtered out due to insufficient expression for reliable analysis. This left 14% of pairs for further classification, where 8% (57% out of the 14% available for further classification) fit into one of four expression diversification groups below, while the remaining 6% did not meet our thresholds. Coexpression for each pair of paralogues in each orthogroup was obtained from this rank-standardized network. For each paralogue pair with non-zero expression in two or more samples, we also computed the fold change in expression across samples and used the absolute values of mean and s.d. of log2-transformed fold change across samples to summarize the degree of expression divergence between the two copies.

We classified the paralogue pairs within each species into different retention categories based on their variation in expression levels and correlated expression across samples. We selected these two axes of variation as they intuitively represent average expression difference (fold change) and specific pattern of difference (coexpression) between gene pairs. We classified paralogue pairs into four broad groups as follows:

-

(I)

Dosage balanced: coexpression > 0.9; mean log2[fold change] < 1, s.d. of log2[fold change] < 1.

-

(II)

Paralogue dominance: coexpression > 0.9; mean log2[fold change] ≥ 1, s.d. of log2[fold change] < 1.

-

(III)

Specialized: coexpression > 0.9; mean log2[fold change] ≥ 1; s.d. of log2[fold change] ≥ 1.

-

(IV)

Diverged: coexpression < 0.5, mean log2[fold change] ≥ 1; s.d. of log2[fold change] ≥ 1.

Paralogues originating from whole-genome, tandem and proximal duplications were obtained using the DupGen_finder pipeline38. WGD pairs with Ks ranging from 0.2 to 2.5, and tandem and proximal duplicates with Ks ranging from 0.05 to 2.5 were used to generate the stacked bar plots corresponding to WGDs and SSDs, respectively, in Fig. 2i.

The gene family size for each classified paralogue pair within a species corresponds to the number of genes in its orthogroup. The expression breadth of a gene corresponds to the number of tissues (among apices, cotyledon, hypocotyl, inflorescence, leaves) where the gene has an average expression greater than 3 TPM. The number of shared tissues expressing a paralogue pair is computed by intersecting the expression breadths of both copies, and ranges from 0 to 5. A gene was considered non-functional if it was annotated as a pseudogene or had an average expression below 3 TPM. Tissue-specific genes for each tissue were identified as genes with the highest expression in the tissue of interest, tissue-specificity score104 greater than 0.7 and with expression greater than 5 TPM in the relevant tissue. Both tissue specificity and pseudogene calling are sensitive to the breadth of tissue sampling, and the collection and incorporation of additional data into this framework would improve the comprehensiveness of the calling of modes of paralogue evolution.

Mapping of loci controlling the S. aethiopicum locule number

The high-locule-count parent and reference accession PI 424860, and low- and higher-locule-count parents 804750187 and 804750136, respectively, were selected as founding parents to map QTLs and their causative variants affecting fruit locule number. Resulting F1 progeny were selfed to generate F2 mapping populations, which were sown in the greenhouse and then transplanted to a field site at Lloyd Harbor, New York, USA, during the summer of 2022. Six F3 populations derived from genotyped (see below) F2 individuals were sown and transplanted at the same location during the summer of 2024. Approximately ten fruits were collected from each F2 individual and the number of locules exposed by slicing each fruit transversely and counting. In the F2 populations derived from 804750187 × PI 424860 and 804750136 × PI 424860, 144 and 135 individuals were phenotyped, respectively (Supplementary Tables 13 and 14). For each population, DNA from 30 random individuals at the low and high ends of the phenotypic distribution for locule number were pooled for bulk-segregant QTL-seq analysis. The DNA from eight individuals of the common parental accession PI 424860 were also pooled to capture parental polymorphisms.

DNA from 15 of the most extreme low- and high-locule count individuals was extracted from young leaf tissue using the DNeasy Plant Pro Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions for high-polysaccharide-content plant tissue. Tissue used for extraction was ground using a SPEX SamplePrep 2010 Geno/Grinder (Cole-Parmer) for 2 min at 1,440 rpm. The sample DNA (1 µl assay volume) concentrations were assayed using Qubit 1× dsDNA HS buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on the Qubit 4 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Separate pools were made for the parents, the bulked high-locule-count F2 individuals and the bulked low-locule-count F2 individuals, with an equivalent mass of DNA pooled from each individual to yield a final pooled mass of 3 µg in each bulk. DNA pools were purified using 1.8× volume of AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter) and the DNA concentration and purity were assayed using Qubit and the NanoDrop One spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), respectively.

Paired-end sequencing libraries for QTL-seq analysis were prepared with >1 µg of DNA using the KAPA HyperPrep PCR-free kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Indexed libraries were pooled for sequencing on a NextSeq 2000 P3 chip (Illumina). Mapping was performed using the end-to-end pipeline implemented in the QTL-seq software package105 (v.2.2.4, https://github.com/YuSugihara/QTL-seq) with reads aligned against the S. aethiopicum (Saet3, PI 424860) genome assembly.

To determine the effects of the two identified QTL on locule number in the populations derived from 804750136 × PI 424860, co-segregation analysis was performed on the full F2 populations by genotyping SaetCLV3 and the minor-effect locus on chromosome 5. For SaetCLV3, a cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence (CAPS) assay was used to genotype a variant in the promoter region of SaetCLV3 linked to the identified CLV3 SV haplotypes. A 1,258 bp region surrounding an AseI restriction fragment length polymorphism in the SaetCLV3 promoter was amplified using the KOD One PCR Master Mix (Toyobo) on template DNA extracted using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide method106 (primers 5431 and 4681 are shown in Supplementary Table 20). To 5 µl of the resulting PCR product, a 10 µl reaction containing 0.2 µl AseI (New England Biolabs) and 1 µl CutSmart r3.1 buffer (New England BioLabs) was incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. The reactions were then loaded onto a 1% agarose gel and electrophoresed in an Owl D3-14 electrophoresis box (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 1× TBE buffer for 30 min at 180 V delivered from an Owl EC 300 XL power supply (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The electrophoresis results were visualized under UV light using the Bio-Rad ChemiDoc XRS+ (Bio-Rad) imaging platform and ImageLab (Bio-Rad) software. The resulting banding patterns were then used to assign genotypes. For the chromosome 5 QTL, primers (primers 5883 and 5884 are shown in Supplementary Table 20) were used to amplify a 425 bp region containing a 1 bp deletion occurring near the summit of the QTL peak using the KOD One PCR Master Mix. The resulting PCR products were purified using Ampure 1.8× beads and were used as a template for Sanger sequencing (Azenta Genewiz). The sequencing results were then used to assign genotype calls at chromosome 5. Presented data are from individuals that were successfully genotyped at both loci.

Conservatory analysis

The Conservatory algorithm (v.2.0)107 was used to identify conserved non-coding sequences (CNSs) within the Solanaceae family (Supplementary Fig. 4b) (https://conservatorycns.com/dist/pages/conservatory/about.php). A total of 26 genomes, including 23 Solanum genomes, two tomato genomes (Heinz and M82) and one groundcherry (P. grisea), were used as references to enable the identification of CNSs irrespective of structural variations among references. Protein similarity was scored using Bitscore108, while cis-regulatory similarity was assessed using LastZ109 score. Homologous gene pairs were required to share at least one CNS. For orthogroup calling, all orthologous genes shared at least one CNS with the reference gene. Gene pairs with a conservation score exceeding 90% of the highest score were classified as paralogues (Supplementary Fig. 4b). A total of 844,525 paralogues was identified across the Solanum pan-genome. Sequence evolution pressure rates (Ka/Ks) for paralogue pairs were calculated using the R seqinR package (v.4.2-36)110. Gene duplication events were classified using DupGen_finder38, identifying whole-genome and transposed duplications for gene pairs recognized by both the Conservatory and DupGen_finder tools. Tandem and proximal duplications were defined based on gene positioning: adjacent genes were considered to be tandem duplications, and genes up to ten genes apart were defined as proximal duplications. All other duplicated gene pairs were categorized as dispersed duplications (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Of the identified paralogues, 23,730 were associated with expression groups and were used to compare relationships between sequence evolution pressure rates and protein and cis-regulatory divergence across different expression groups. Homologues, orthogroups and paragroups were identified, and the relationships between protein and cis-regulatory elements were visualized using custom scripts, which are available at GitHub (https://github.com/pan-sol/pan-sol-pipelines). See Supplementary Table 5 for statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

All statistical tests were performed in R. For the quantitative analysis of fruit locule numbers in Figs. 3f and 5c,d and Extended Data Fig. 5b,c, n represents the number of fruits quantified. Pairwise comparisons were conducted using Dunnett’s T3 test (R package PMCMRplus v.1.9.10) for multiple comparisons with unequal variances, with the default parameters. Statistical tests and the resulting P values are presented in Supplementary Tables 5, 9, 15, 17 and 19.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.