Against the Odds: Women Pioneers of Science John Gribbin and Mary Gribbin Icon Books (2025)

What is it with toilets? In domestic households, men and women use the same ones without a fuss, but at some point in history it became etiquette for toilets in workplaces to be segregated. And in supposedly male environments, it meant that there simply weren’t any for women. It then became absurdly easy to use the lack of appropriate toilets as an excuse to deny women a role in those environments or, if they did take a job there, to make their lives difficult.

‘Male-dominated campuses belong to the past’: the University of Tokyo tackles the gender gap

Toilets come up in several of the 12 stories selected for John and Mary Gribbin’s gallery of female pioneers in science, Against the Odds. In the opening years of the twentieth century, physicist Lise Meitner, banished to a basement because she wasn’t allowed to work in the chemistry laboratories of what was then the Royal Friedrich Wilhelm University of Berlin, had to use the toilets in a neighbouring restaurant. During the 1950s, computer pioneer Lucy Slater, while developing the operating system for an early computer at the University of Cambridge, UK, smashed the sanitary equivalent of a glass ceiling by simply using the men’s toilet (singing loudly to signal her presence). And in 1964, Vera Rubin became the first female astronomer who was officially allowed to use the big telescopes at the Mount Wilson and Palomar observatories in California, overturning a ban that had been partly, but explicitly, based on the lack of a women’s toilet.

Science trailblazers

Compared with unequal pay for the same work, the reality of men with fewer qualifications being promoted ahead of them and the frank refusal to recognize that a married woman with children might be capable of a career, the toilet issue was probably a trivial annoyance to these women. But it symbolizes how, for centuries, women have been considered unsuitable as scientists for reasons that have nothing to do with their ability or commitment.

The Gribbins’ aim is to “highlight the achievements of women who overcame the odds and achieved scientific success … as society changed over about 150 years”. They don’t justify their selection, other than to note that the women featured (ordered by year of birth) collectively cover the period. But it is startling that physicist Chien-Shiung Wu is the only scientist who is not white or born in a Western country (and she spent most of her career in the United States). The ‘hidden figures’ — African American women who calculated trajectories for early NASA space missions — remain hidden. Many girls won’t find a role model who looks like them in the book.

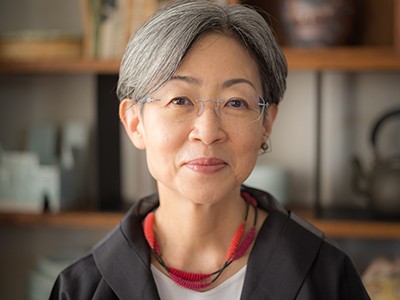

Physicist Chien-Shiung Wu made instrumental contributions to the field of nuclear physics.Credit: IanDagnall Computing/Alamy

With that caveat, the Gribbins tell the stories with an adroit mix of anecdote and exposition. There is a bias towards physical sciences, perhaps reflecting John Gribbin’s background in astrophysics. Some of those featured (such as crystallographer Rosalind Franklin) are close to being household names, others (geophysicists Eunice Newton Foote and Inge Lehmann) are much less familiar. Three of the women (chemists Irène Joliot-Curie and Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin and geneticist Barbara McClintock) won Nobel prizes; two (Meitner and Wu) should have done.

Some of the women were less celebrated during their lifetimes. It took 100 years for historians to uncover the work done by Foote, as a wealthy ‘lady amateur’ working in her home lab in New York state. She demonstrated that water vapour and carbon dioxide absorbed energy from sunlight and so could increase global temperatures. Her 1856 paper included the statement that if “the air had mixed with it a larger proportion [of CO2] than at present, an increased temperature … would have necessarily resulted”. Three years later, John Tyndall, unaware of Foote’s work, performed the experiments that are generally credited with establishing the nature of the ‘greenhouse effect’.